Kurosawa famously said that “not to have seen the cinema of [Satyajit] Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.” Ray’s opera prima, পথের পাঁচালী Pather Panchali [Song of the Road] (1955), fits that description admirably.(*)

Labelling it – as it is often done – a “neorealist” film misses, though, the whole point, as it both banalises its formal beauty and oversimplifies its content.

To begin with the latter (the content): were one to view it as a “neorealist” film – in the tradition of Rossellini’s and De Sica’s, which Ray nonetheless admired – one would infer that what it shows is the relations among five major characters of a Brahmin family (Apu, his sister, their parents, and an old relative of theirs) and a number of secondary characters (the villagers) in early-20th-century rural Bengal against the background of modernisation; characters whose problems, hopes, and frustrations make of social progress the solution to social injustice and misery, which are thus opportunely denounced. And since the mother is the character that more clearly sees all this and the one that internally rebels against it, it would be tempting to infer that, while Apu is the film’s protagonist, in the sense that he is the character through whose eyes part of the film is told and the one who is given a chance to finally grow outside of the village, his mother is the second main character of the film, and that everyone and everything else (characters, circumstances, and events) stands in respect to the two of them like the third leg of a tripod.

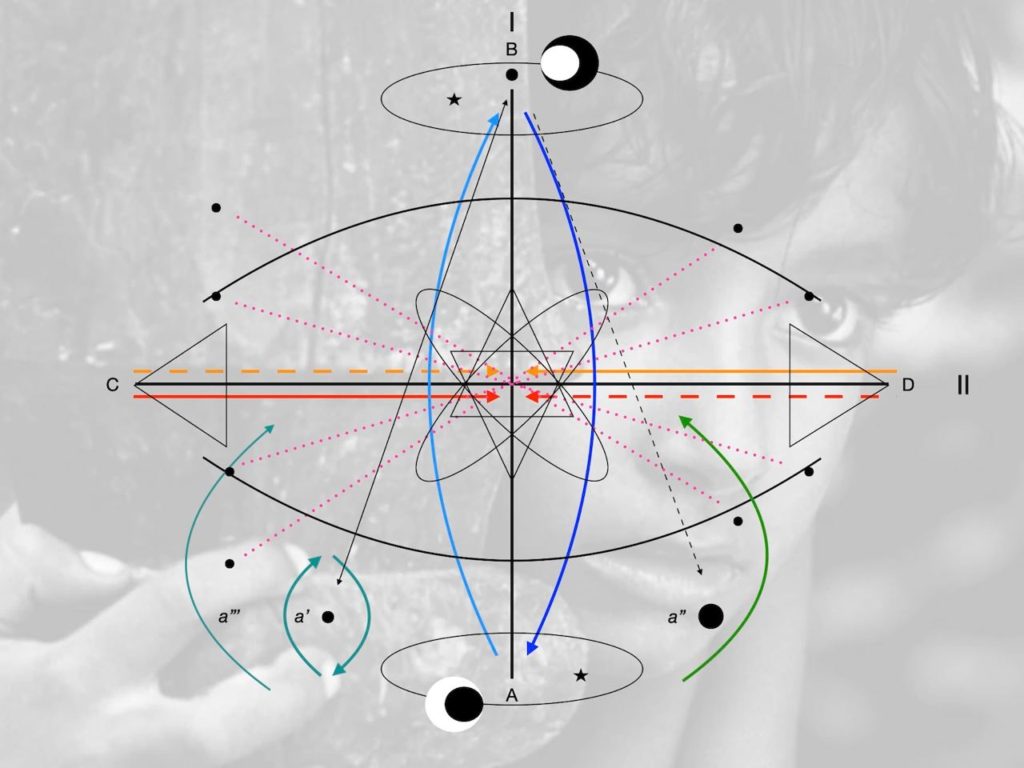

It would be then possible to diagram the aforementioned relations as follows:

The opposing horizontal arrows show the internal conflict between Sarbajaya (Apu’s mother) and Harirar (her husband, an impoverished Brahmin): while she perceives the difficulties they are experiencing with gravity (thus her arrow’s full trace), he does not (hence his arrow’s discontinuity) until their daughter Durga dies and their house is destroyed by a tempest, which finally leads him to realise they must leave the village for the city. Hence the two triangles, Sarbajaya’s and Harirar’s, which point in opposite, almost irreconcilable, directions. In turn, Durga’s and Apu’s childhood (especially Durga’s) unfolds in intimate relation with Indir’s (the grandmother’s) decline: Durga steels for her fruits from an orchard which used to belong to them but some relatives have deceitfully appropriated. Unwilling to be the target of the villagers’ gossip Sarbajaya kicks Indir and Durga out of their house, Indir dies, and, unlike her brother Apu and their cousins who will make their way into adulthood, Durga dies as well. As for the villagers, there are Sarbajaya’s cousins and their own children, i.e. Durga and Apu’s cousins, a merchant who plays the role of school teacher, the candy man, a company of itinerant actors, and other various secondary characters, including Harirar’s potential employers (whom we are told about but never see) and several animals.

And yet there is so much more…

In terms of the film’s overall narrative structure, to begin with. The film divides into five more-or-less-differentiated parts that turn around the film’s major themes: (1) the contraposition between life’s joy, beauty, and eternity as it is immanently and contemplatively experienced by Indir, Durga, and Apu, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the adult world with its meanness and cruelty; (2) the painful initiation one must undergo to enter that adult world; (3) the latter’s qualities (its violence, hope, etc.); (4) death; and (5) the need to go on living.

Furthermore, Ray insists that the key to his film is its poetry.(**) By poetry, though, one must not only understand the visual delicacy of the film, which is astonishing, but also the film’s enunciative structure, i.e. the way in which the film shows what it shows, which in cinema – like in literature – is never an additament, since what we see and how we see are one and the same thing.

The film’s enunciative structure can be diagramed thus – notice its proportions vis-à-vis how the previous, simplified diagram, which we reproduce in red within this new, broader, grey one:

To explain this composite diagram – which witnesses to the film’s formal beauty not less than the aforementioned delicacy of its images – a few chromatic nuances are in order in the first place:

There are two main axes perpendicular to one another: one vertical (= I or AB) and the other one horizontal (= II or CD).

Above and below CD there are two curved lines that, were it not for their curvature, would run parallel to that axis. Those two lines are symmetrical and describe an elliptical region within them that extends from C to D and vice versa. It is the central region of the diagram but also the most populated one. The region of adulthood thus framed by Apu’s mother (C) and father (D).

It is outside of that region that A and B stand. A is the world of infancy, represented by Durga (a’), Apu (a’’), and one of their cousins, a young girl who gets married (a’’’); by getting married she enters the adult world which Apu, too, will enter one day, but from which Durga is excluded due to her death. In turn, B is the old age, represented by the grandmother.

A and B, B and A, communicate naturally, permanently, and reciprocally (thus the two blue arrows). Actually, they mirror each other and are thus inseparable (a feature suggested by the two small ellipses found in them). Furthermore, they are similarly in contact with life’s continuity and intensity. Durga and her grandmother are the only ones who repeatedly interact with the animals and plants of the house (represented by the stars inscribed inside their respective areas) as though they were also part of the family, feeding them, watering them, etc., in short caring for them. While the adults (Sarbajaya and Harirar) argue, the grandmother cradles Apu and sings to the immensity of life in the middle of the night; or else she, Durga, and Apu sing together. It is the grandmother, moreover, who shows the greatest excitation when she comes to know of Apu’s birth; upon getting the good news she decides to return home despite Sarbajaya’s enmity towards her. She is also the one who tells the children the stories of old, i.e. the stories of the ancestors, thus suturing past and present by recourse to her memory. Lastly, just as Indir presages her death, Durga presages hers; and the two of them die: Durga after having unconsciously sung her own death while living, the grandmother after having sung to life and paid homage to it (thus the circles bordering regions A and B, the relation between which is, accordingly, one of inverse proportionality).

As for the green arrows, they represent the transition from childhood to adulthood: fulfilled by the cousin (a’’’), aborted in the case of Durga (a’), and forthcoming for Apu (a’’).

In turn, the three black spots (other than a’, a’’, and a’’’) placed either inside the A region (two on the right side of the diagram) or in its limit (one on the left side of the diagram) stand for those adults who manage to relate with the children, be it positively (the candy man), negatively (the improvised teacher), or indifferently but influentially (the actors).

Let’s now look into the CD region comprised between the curved lines located above and below Axis II, the region of adulthood. Sarbajaya’s full arrow and Harirar’s discontinuous arrow (both in red) are now supplemented by two other arrows: Sarbajaya’s discontinuous arrow and Harirar’s full arrow (both in orange). For if it is true that Apu’s mother is wiser than the father, it is also clear that the father’s heart is less poisoned, more innocent and more cheerful, than his wife’s, who, unlike him, proves for example, cruel to both Durga and Indir and remains obsessively resentful towards the latter. What Sarbajaya lacks Harirar has, and vice versa. They, too, are in contact with other adults and children (represented by the black spots) who turn around them (hence the pink dotted lines) be it in friendly or unfriendly, closer or more distant, terms (e.g. Sarbajaya’s cousins and their own children, the other villagers, Harirar’s potential employers, etc.).

Finally, at the very centre of the diagram – in the intersection of axes I and II – various geometrical figures are drawn, namely, two intercrossing ellipses whose dynamism wants to stress the unquietness characteristic of all adult transactions, and two intercrossing triangles which form a star that points to A and B: unlike C’s and D’s opposite-looking triangles, these two unfold into one another thus emphasising A and B’s the mirroring reciprocity.

Shortly before filming Pather Panchali, Satyajit Ray had made Jean Renoir’s acquaintance and worked as his assistant in the filming of The River (1951), which is rightly taken to be a cinematographic mirror of life’s course. In his opera prima, Ray, instead, builds something like a crystal capable of reflecting life’s structure and its essence, as portrayed in the third diagram above: eternity is immanently experienced by children and old people alike who – one may infer – thus stand in a vertical height never attained by those whose age is no longer that of a child and is not yet that of an old person; and regardless of the many vicissitudes that life brings, which adults are obliged to deal with, life at its most is found in that vertical domain alone.

This is a beautiful reminder, moreover, in a world like ours in which old people are either locked up in nursing houses or offered fitness and spa vacations – a world in which old people is no longer old people – and in which children haven been transformed into proto-adolescents – a world in which children are no longer children.

(*) Together with অপরাজিত Apajarito [The Unvanquished] (1956) and অপুর সংসার Apur Sansar [The World of Apu] (1959), the film is the first one of what has come to be known as Apu’s Trilogy. It is recommendable to watch the film after its 2015 restoration by The Criterion Collection and the Film Archive of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which was premiered in the Museum of Modern Art of New York (MoMA).

(**) Andrew Robinson, The Apu Trilogy: Satyajit Ray and the Making of an Epic (London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2011), p. 178.

Subir Banerjee playing Apurba Roy (Apu) in Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali [Song of the Road] (1955)