For Luigi Attademo

We have recently written on Schumann’s Morning Songs, Op. 133, for piano. Like these, the Theme and Variations in E-flat major for piano WoO 24, also know as Gesitervariationen (Ghost, or Spirit, Variations, due to Schumann’s self-declared source of inspiration as it is mentioned in Clara Schumann’s diary of February 17, 1854), are among Schumann’s latest works. Schumann finished it shortly before his mental collapse.

As the title suggests, it comprises a series of variations (five) around an opening theme. This is a recurrent pattern in Schumann’s music (cf. e.g., among his works for piano, Variations on the Name “Abegg,” Op. 1; Studies in the Form of Free Variations on a Theme by Beethoven, WoO31;Symphonic Studies, Op. 13; Kreisleriana, Op. 16; Blumenstück, Op. 19; Andante and Variations, Op. 46, etc.).

The theme presents a binary structure, only the second half of which undergoes repetition. As Eri Nakagawa remarks, “this [binary] structure remains the same through all five variations except for the last one, which has light extensions in the second half.”(⦼) Furthermore, as often with Schumann, the melody is built on descending scales, semitone slides, and phrasal prismatic multiplications that, like in Debussy’s case (in respect to whose music Schumann’s is somewhat more profound and certainly much more fond of asymmetry, though), turn and re-turn what thereby ends up resembling “the facets of a jewel, each reflecting a different light and colour”(⦶) – was this intrinsic formal hyper-complexity (which contrasts with Liszt’s formless ornamental complexity) the cause, perhaps, of Chopin’s repeated and impolite dismissal of Schumann’s music, together with Schumann’s refusal to privilege cantabile melodies over harmonically-oriented melodic progressions, inversions, superimpositions, etc.?

Here is the theme, performed by András Schiff – all performances below are his, as well

“The first variation,” writes Nakagawa, “decorates the theme with triplet figures in the inner voice”(⊕). Thus, it can be argued, it organises the melody in a spring-like manner, as if sprouting forth:

Variation #1

In turn, the third variation employs triplet figures at a higher pitch.(⊗) The effect, then, is rather like rain, in the sense that the triplets seem tofall on the melody:

Variation #3

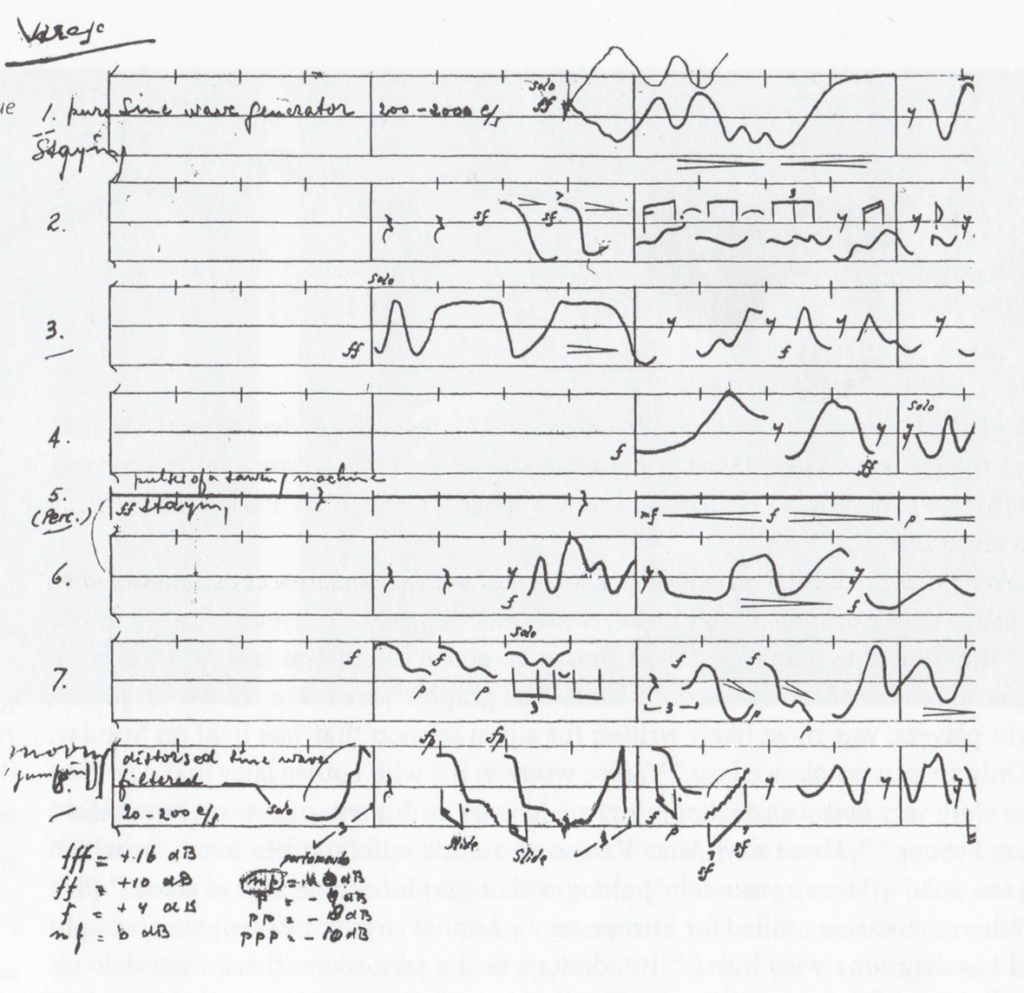

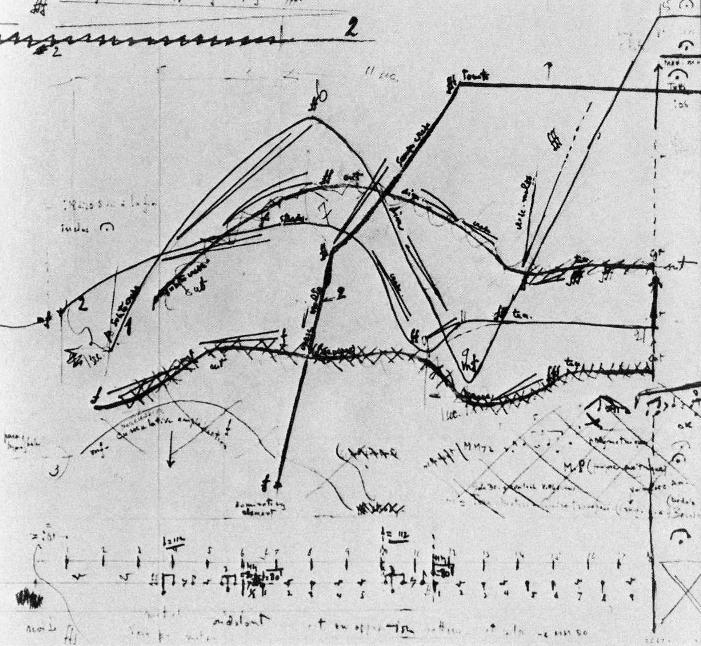

It is important to understand that, by using the terms “spring” and “rain” we are not exactly trying to picture the music in sensible terms: we are merely describing the general vectors of its movement, in both conceptual and imaginary terms (a spring moves upwards, rain downwards). What is gained in this way is an abstract depiction – similar, in a way, to those contained in the score of Varèse’s Poème électronique:

Edgar Varèse, Poème électronique (1958), excerpt

Edgar Varèse, Poème électronique (1958), excerpt

which do resemble Varèse’s own abstract paintings:(⊖)

Painting by Edgar Varèse, oil on canvas (1951)

(You may just as well think in Kandinsky’s abstract pictorial rendering of musical melodic lines, harmonic intervals, and rhythmic blocks; or meditate on the content and form of one of Lévi-Strauss’s latest writings: Regarder écouter lire [To watch to listen to read], whose title intentionally avoids introducing any signs of punctuation, any commas, between the three verbs in the infinitive which form it.)(✺)

Let’s now go back to Schuman’s music – which, on the other hand, has absolutely nothing to do with Varése’s non-musical exploration of sound (and noise).

The second variation is strictly canonical, i.e. it displays imitative counterpoint. Thus with it one enters, this time, in the domain of echo:

Variation #2

In contrast, in the fourth variation the key is changed to G minor, which, as Nakagawa recalls, is the “mediant key” of the original key of E-flat major.(⦿). Put otherwise, G minor is the key that serves as a mid-way point between the tonic of the E-flat major scale, i.e. E-flat (which provides the tonal centre to the composition), and its corresponding dominant, i.e. B-flat (which, next in importance to the tonic, is responsible for the instability that requires the tonic’s resolution); that is to say, G minor stands, like any mediant key, half way between the two extremes of a given polarity. Call it earth and water. Schumann: “As a child I used to place the music upside down on the music stand and revel in the strangely intertwined notational structures – as I subsequently revelled in the upside-down palaces reflected in the canals of Venice.”(⊙) Notice that their reflections stand half way between earth and water, as an illusion. From the domain of echo (which is that of a strict reflection) we thus enter into that of a mirror (or inverted reflection):

Variation #4

Lastly, the fifth and final variation “is written a new rhythm,”(⦷) a somewhat current rhythm: the melody transforms into a stream:

Variation #5

In short, the theme undergoes five transformations:

Again, the terms used to describe each transformation must be read as conceptual metaphors, that is, notional or abstract manners of picturing Schumann’s Geistervariationen.

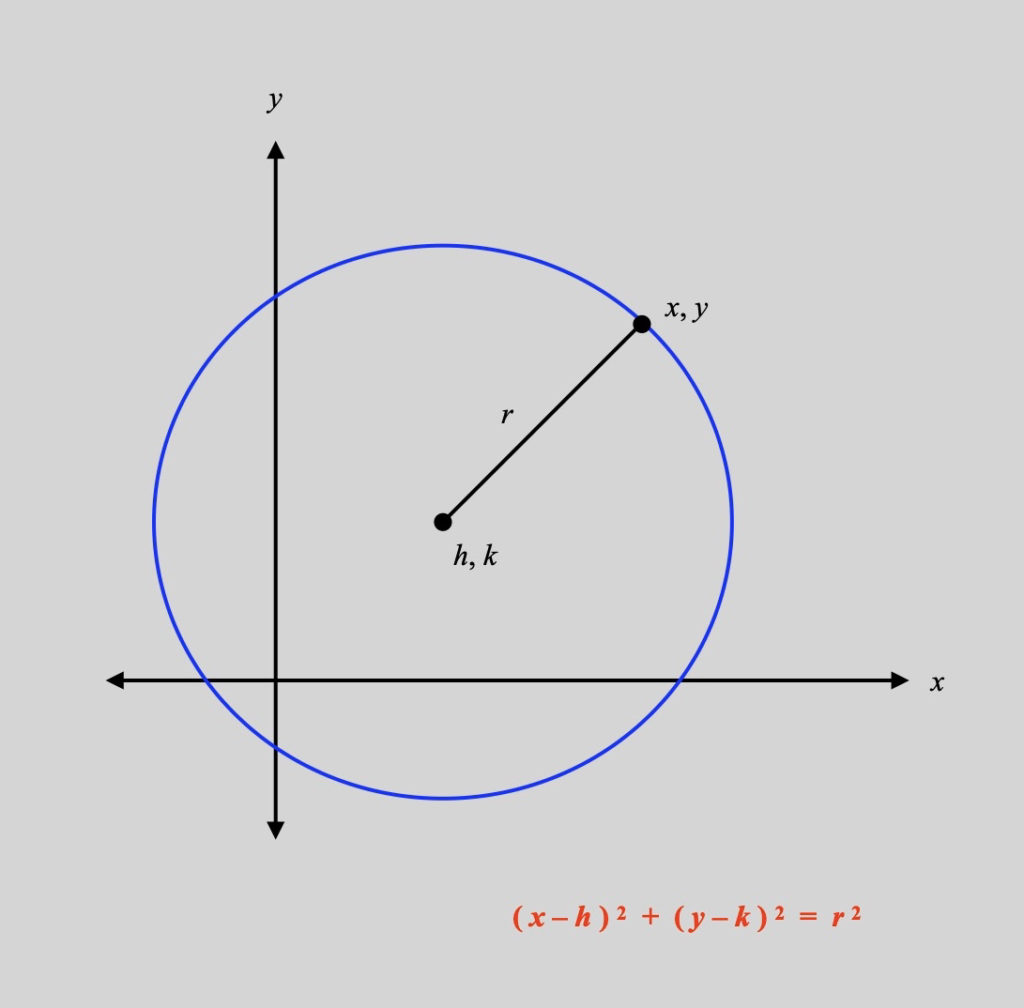

These conceptual metaphors do not necessarily depend on a detailed technical analysis of the work itself, but own its immediate listening. Yet Leibniz would have said that they express the same thing, like an algebraic equation (in red in the image below) and the drawing of a circle (in blue) variously express the idea of a circle in two different, albeit not contradictory, ways.(⊛)

Now, it can be said that if in our previous entry we wrote about the soul of Schumann’s music – or, rather, about one of its many aspects – this time we have done it on the variations of its spirit or transformations of its mind.

(⦼) Eri Nakagawa, “Schumann’s Last Piano Work: Geistervariationen” (Journal of Urban Culture Research 21 [2020]: 25–37), p. 29.

(⦶) William John Robinson, The Pianoforte Works of Robert Schumann and Their Influence on Later Pianoforte Composers (Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1932), p. 111. Cf. Mitsuko Uchida’s allusion to Schumann’s contemporaneity here:

(⊕) Nakagawa, “Schumann’s Last Piano Work,” p. 30.

(⊗) Ibid., p. 32.

(⊖) On which see Edgard Varèse and Alfred L. Copley, “Edgard Varèse on Music and Art: A Conversation between Varèse and Alcopley” (Leonardo, 1.2 [1968]: 187-195).

(✺) Claude Lévi-Strauss, Regarder écouter lire (Paris: Plon, 1993).

(⦿) Nakagawa, “Schumann’s Last Piano Work,” p. 33.

(⊙) Robert Schumann, Schumann on Music: A Selection from the Writings (translated, edited, and annotated by Henry Pleasants; New York: Dover, 1965), p. 141.

(⦷) Nakagawa, “Schumann’s Last Piano Work,” p. 34.

(⊛) See further Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Philosophical Papers and Letters (a selection translated and edited, with an introduction, by Leroy E. Loemker; Dordrecht, Boston, and London: Kluwer, 1989), pp. 207-208 (“What Is an Idea?”).