It was Herder (1744–1803) who coined the term Volkskunde (pl. Völkerskunde), which may be translated as the “knowledge” of the “popular traditions” and “cultural practices” of a given “nation” or “people.” But it was not until 1839 and 1843 that the first learned ethnological societies were established in Paris and London, respectively. The Ethnological Society of Paris would give way in 1859 – the same year in which the Anthropological Society of Washington was created – to both the Ethnographical Society of Paris and the Anthropological Society of Paris, whereas the Ethnological Society of London merged in 1871 with its rival the Anthropological Society of London – which had been founded in 1863 – to create the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. In turn, the Berlin Society of Anthropology, Ethnology, and Prehistory was established in 1869; the Anthropological Society of Vienna in 1870; and the Italian Ethnological Society in 1871. Anthropology as a social science was born.

Its basic features were: (1) The idea of human physic unity and humankind’s evolution: regardless of their different “races,” men were all similar and their cultural evolution observable. (2) The notion, therefore, that all human groups basically face the same problems under different circumstances and adopt different means to cope with them. (3) The possibility of faithfully describing the usages of other human groups, especially with the assistance of fieldwork; and (4) the possibility of theorising thereof through comparison.

Throughout the 20th century, the progress achieved regarding 3 and 4 (in terms of methods of observation, rules of description, and the elaboration of theories) has been remarkable. Interestingly, however, 1 and 2 remained largely unquestioned until the late 1950s or early 1960s. Since then, the view that all human groups ultimately face the same problems but invent different means to deal with them has become increasingly problematic; the view that something like human cultural evolution is observable, untenable.

For, as Roy Wagner says, one thing is to ask the question: “How do these people solve our problems with their means?,” and another one to ask instead: “How do they […] transform our meanings with their own problems?”(⦼) The former question is unconsciously projective; the latter one, duly prudent. As Wagner himself stresses elsewhere, “projection […] is the means by which we […] extend the realm of the ‘known’ [to us] by applying the range of our [own] symbolization to the data and impressions of the ‘unknown’ [to us];” as a consequence, rather than being challenged to discover something else, “we [merely] find [in it] what we want to find,” thus dissolving that which is unknown to into that which is known to us.(⧀) Or, in Viveiros de Castro’s words: “When a shaman shows you a magic arrow extracted from a sick man, a medium gets possessed by a god, a sorcerer laboriously constructs a voodoo doll, we [tend to] only see one thing: Society (belief, power, fetishism). In other words, we only see ourselves.”(⧁)

There is probably no exaggeration if affirming that it is Lévi-Strauss’s La Pensée sauvage (1962, translated into English in 1966 as The Savage Mind) that one finds a first conscious attempt to reverse this. By “savage,” from the Latin silvaticus, “of the forest,” one, of course, must understand here “untamed […] as distinct from domesticated for the purpose of yielding a return.”)(⊕)

To cut the matter short: it was in La Pensée sauvage that the study of different thinking modalities or ways of formulating similar problems rather than other means to solve the same problems was overtly acknowledged as anthropology’s subject matter. That is to say, even if the problems may not be altogether different from one human group to another – thinks Lévi-Strauss’s – they are not exactly the same; thus his well-known notion of “variations.”

The so-called “ontological turn” in contemporary anthropology has come to radicalise this view. As Paolo Heywood underlines, the ontological turn “aim[s] to take difference seriously and understand it as best we can on its own terms.”(⊗) This requires to understand that, eventually, problems may indeed differ from one context to the next, and that different problems do not only elicit different cultural responses, but witness to different ways of semiotising reality.

Now, when reality is variously semiotised, reality itself changes. Put otherwise, different cultural views do not only amount to different interpretations of the world, but convey different realities. In this sense, the ontological turn goes far beyond multiculturalism, which keeps difference within the epistemological sphere (how things are interpreted): there is but one world and many interpretations of it. Conversely, from the perspective of the ontological turn there is not one but many different worlds, which implies that difference is made extensive to the ontological domain, i.e. to what things are: reality is different for me from what it is, say, for a Bororo, not less than what it is in turn for a parakeet. The ontological turn does not advocate for multiculturalism, but for “multinaturalism,” to borrow from Viveiros de Castro.

Lévi-Strauss, then, was the first anthropologist to move, albeit hesitantly, in this direction. In turn, Roy Wagner was the first one to push it forward and to fully assume its consequences, at the expense of which – he says – anthropology becomes a “mobile army” of all-too-inexact and misguiding notions “deployed so as to outflank the Enigma” of reality’s inherent plurality.(⊛)

Wittgenstein, of whom Wagner was an excellent reader,(⦿) anticipated the view that reality is inherently multiple, i.e. that it is ontologically and not only interpretatively multiple, in his Philosophical Investigations 2.11 (1953), where he gave the example of an image which is neither a duck nor a rabbit, but a rabbit-duck.

If you only see a rabbit, Wittgenstein comes to say, you will affirm: “This is a rabbit.” But when you become aware of the duality (it is a rabbit, but it is also a duck!) you will probably change your affirmation for one of the like: “Now I see it as a rabbit.” That will inform anyone about your interpretation of what there is in the image, but the duality is there and is susceptible of being perceived as such. Accordingly, “It’s a rabbit-duck” would be for Wittgenstein not an interpretative statement, but a perceptual report – and thereby, one may infer, an ontological statement.

Inevitably, this transition from the epistemological to the ontological claims several victims, the first and the most important of which is the notion of “fact.”(⦶) What you take to be a fact, a Bororo or a Yekuana may not see it that way.

Take, for instance, the following conventional proposition: “The Yekuana believe the Amazonian crimson-crested woodpecker [Campephilus melanoleucos] to be their hero and first shaman.” Belief is a misnomer here, as the equivalence:

crimson-crested woodpecker ≣ shaman/hero

results from strict conceptual parallelism relying on an extensive binary logic: bright-coloured beings like the crimson-crested woodpecker, and dynamic social roles like those of the warrior and the shaman, belong in the same ontological category. At stake here is conceptual classification rather than belief. As for the equivalence:

crimson-crested woodpecker ≣ the first shaman

it displays, in turn, a likewise logical and, this time, mathematical (arithmetic, ordinal) cum empiricist analogy: the first shaman/hero is equivalent to the first bright-coloured bird that makes its appearance at dawn. It would be mistaken, therefore, to take the Yekuana’s “belief” to be a fact. Nor is it possible to affirm that, independently from what the Yekuana “believe,” it is a fact that the crimson-crested woodpecker is simply a bird (Campephilus melanoleucos). In the Yekuana world, it is something else. Once more, we are at the level of perceptual reports rather than interpretative statements; for seeing the crimson-crested woodpecker merely as a “bird” (which is an idea of ours, i.e. an analytical tool by means of which we turn reality meaningful for us) only amounts to interpret it. In fact, the crimson-crested woodpecker is many things, including, first and foremost perhaps, what it is to itself, not to talk of what it is for a jaguar, an anaconda, or an ant.

How, then, is it possible – if it is anymore, one may fear! – to share views and experiences in a pluriverse in which no translation from one meaningful world to another one can deem entirely faithful? Through the self-awareness of the relativity of one’s own views and the patient questioning of the limits of one’s own conceptual imagination. The example of the crimson-crested woodpecker given above proves that, albeit being far from perfect (for it will be hard for us, anyway, to see a crimson-crested woodpecker as a Yekuana sees it), translation is possible all the same, even if it can only be approximate: we are able to imagine a world in which what we call “dynamic social roles” and what we call “bright coloured beings” would belong together, ontologically speaking. Viveiros de Castro calls it “translation” as “controlled equivocation.”(⊙)

But this means too that anthropology is always about “sticking one’s neck out through the looking-glass of ontological difference.” Or an adventure into the otherwise. Or, in short, an heterology – the science of otherness par excellence. Our own otherness included. Patrice Maniglier would rightly say thus that it is the “ontology of ourselves as variants.”(⊜)

(⦼) Roy Wagner, Asiwinarong: Ethos, Image, and Social Power Among The Usen Barok of New Ireland (Princeton and London: Princeton University Press, 1986), p. xii.

(⧀) Roy Wagner, The Curse of Souw: Principles of Daribi Clan Definition and Alliance in New Guinea (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1967), pp. xviii-xix.

(⧁) Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Who Is Afraid of the Ontological Wolf? Some Comments on an Ongoing Anthropological Debate” (Cambridge University Social Anthropology Society [CUSAS] Annual Marilyn Strathern Lecture, Cambridge, May 30), p. 14.

(⊕) Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind (La Pensée sauvage) (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1966), p. 219.

(⊗) Paolo Heywood, “The Ontological Turn” (in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, ed. F. Stein, S. Lazar, M. Candea, H. Diemberger, J. Robbins, A. Sanchez, and R. Stasch). See further Martin Holbraad and Morten Axel Pedersen, The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017).

(⊛) Wagner, Asiwinarong, p. xii.

(⦿) See e.g. Roy Wagner, The Logic of Invention (Chicago: HAU Books, 2019), pp. 19-57.

(⦶) Wagner, Asiwinarong, pp. xii-xiii.

(⊙) Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Perspectival Anthropology and the Method of Controlled Equivocation” (Tipití 2.1 [2004]: 3-22).

(⦷) Viveiros de Castro, “Who Is Afraid of the Ontological Wolf?,” p. 18.

(⊜) Patrice Maniglier, “Anthropological Meditations: Discourse on Comparative Method” (in Comparative Metaphysics: Ontology after Anthropology [ed. Pierre Charbonier, Gildas Salmon, and Peter Skafish; London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2017, pp. 109-131]), p. 127.

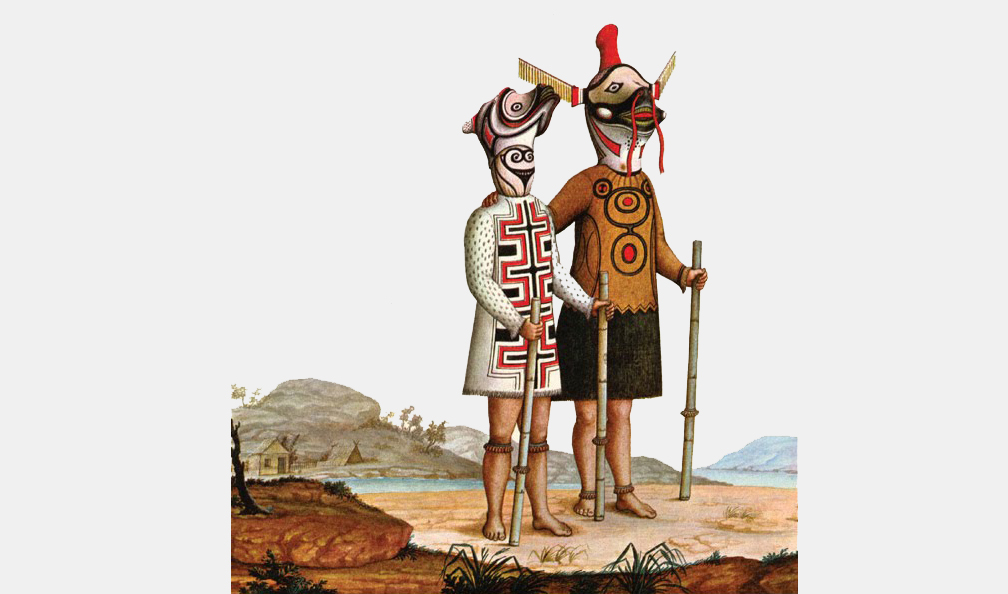

Drawing of two masked Jurupixuna, a now extinct Amazonian tribe, registered during Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira’s naturalist expedition to the Amazon (1783–1793) for the Portuguese crown