Objects(*) are the product of multiple relations – or, rather, their crystalizations. They form at the intersection of relational nodes. Where things touch each other and get enmeshed, new objects appear. As Jeffrey Cohen writes, “medieval writers […] described thunderstones that drop with fire from the sky, rocks that emerge through the subterranean lovemaking of the elements, rubies that tumble along river beds from Eden, diamonds that travel the world in the holds of ships, lodestones exerting irresistible pull, gems that cure diseased bodies and pulse with astral energies.”(⦼) Thus Medieval stones had agency, they told and retold otherwise untold stories that one could listen to if one were willing, or able, to do so. In other words,Europeans once viewed stones not just as things more or less unnoticed one could pass by, but as things that shine forth with life: memories, stories, powers, that is, relations.

Are stones really alive, though? What do we mean by saying that something is “alive?”

For the Karrabing (an indigenous group from Australia) landscapes and things speak with manifold voices, and it is essential to interpret well what those voices say. The durlgmö (which white people call a sea monster fossil, a plesiosaurus), observes Elizabeth Povinelli,

may have buried itself as a statement of anger or jealousy – jealousy that the women had cared more about other places and things. These statements of neglect – a statement understood as an expression through a material shift – often create deserts, dry patches, and absences as the signs that a form of existence had turned its back on that which was within it, dependent on it but careless toward it. To avoid the malevolent effects of such jealousy one ha[s] to show one care[s] by going through the effort of visiting, talking about, and interpreting the desires of things. One ha[s] to protect them from being unhinged and distended.(⧁)

Things and places may feel, desire, and demand some kind of reciprocation, just like humans do, and they can be, as a result, jealous and malicious, or else benevolent and loving. This game of interpreting and producing meaning is a life/death game in the case of the Karrabing or any other indigenous group, as these are either (a) the custodians of what there is, and are thus responsible for its stability and well-being, in addition to being (b) another piece in a puzzle-like ecosystem, i.e. one among other types of other-than-human “humans”; or else (c) they play other roles which nonetheless help them to be, instead of distancing them from being, in a more intimate relationship with their environment, since understanding the latter is absolutely vital forextramodern human groups.

In short, medievals discerned relations in stones, and it would be safe to deduce they established relations with these – relations which, in turn, helped them to relate to the world in a rather complex manner. On their part, the Karrabing regard things and places as being inherently animate, and relate to them accordingly. And many other similar examples could be supplied: the Tukanoans see objects as forming a living system of which they, too, form part, and so on and so forth. In all the aforementioned cases communication, then, is not restricted to the human alone, since the other-than-human is always the basis on which any human world is built. Hence, it is vital to understand that Other.

Elsewhere, we have argued that seeing is always a learned way of seeing, and hence is never objective or impartial. Some contemporary philosophers suggest otherwise in an attempt to “eliminate all [human] thinking about the object, in order to allow the object just to be, in and of itself.”(⊕) As if the true life of any object would begin beyond the relations we (or others) establish with them and be meaningful in itself, independently from the interpretations we (or others) make of them! There is no extra-relational life, and there are no objects in themselves. As Tim Ingold puts it,

since the substance of the stone must be bathed in a medium of some kind, there is no way in which its stoniness can be understood apart from the ways it is caught up in the interchanges across its surface, between medium and substance […] Stoniness, then, is not in the stone’s ‘nature,’ in its materiality. Nor is it merely in the mind of the observer or practitioner. Rather, it emerges through the stone’s involvement in its total surroundings – including you, the observer – and from the manifold ways in which it is engaged in the currents of the lifeworld.(⊗)

In a world like ours, though, in which the understanding of the Other no longer seems to be necessary, relations tend to be likewise impoverished. Things and places no longer speak, nor do they posses agency. Moderns have made their own environments without any consideration for the voices of the places and things they dominate. Domination lacks in conversation; thus only one voice, the human voice, is heard in the cities, while relations with the non-human others have become so very poor in these that such others are barely noticed.At most, they are perceived to be “nothing but things,” “lifeless things,” and this on behalf of what is called “objectivity.”

Hume was the first to separate between values and facts, and thereby to differentiate folk “beliefs” or native “views” from what is “factually” or “objectively” true: for him stones were just stones and mountains just mountains. Poetry (be it in form of words, musical notes, or colours) has always been a healthy spot on the diseased modern mind, as it still sees rocks and mountains as something more than just rocks and mountains. Yet it, too, has been disempowered by being confined in the domain of “art,” where it lacks capacity to affect what is taken to be objectively real.

On the other hand, the modern world of relations reaches its peak around, and in function of, the human; and while, as we have said, the “external” relations of humans with other-than-humans have been considerably impoverished, inter-human relations have become all the more intricate. In short, the more “disconnected” moderns have become vis-à-vis their Others, the more “connected” (⊛) to themselves they have become in turn. As Davi Kopenawa insightfully notices, they “only dream of themselves.”(⦿)

But objectively speaking, then, is a stone or a mountain alive or not? The question itself is the proof that who whoever asks it has hardly felt the vital need to communicate with a mountain or a stone; the relations already established (or not) with them are such that who makes such question sees a priori the stone and the mountain as two inanimate, alien things.

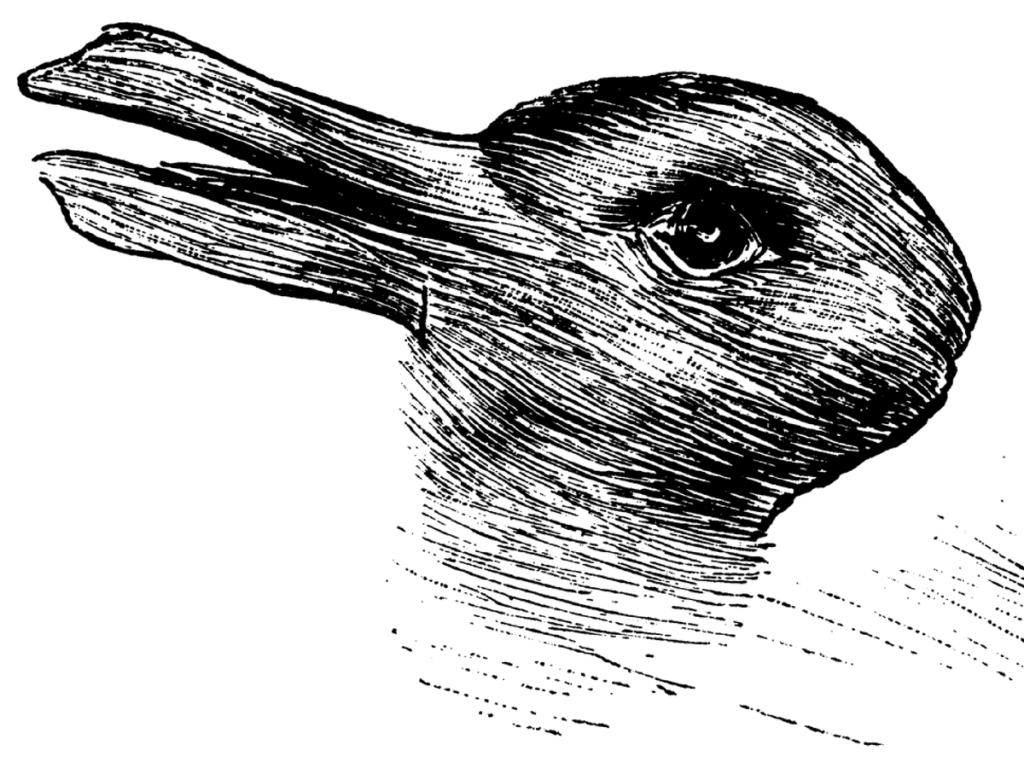

Yet things are what they are always in relation to us, or to an ant or a cat, which perceive stones or trees in entirely different ways; and this means there are no things-in-themselves that cannot be accessed. On the other hand, and for the same reason, our knowledge is always situated, and thereby too perspectival, as Leibniz intuited long before Hegel dreamt of its absoluteness. But let’s leave Hegel for another day, if only for the reason that, instead of understanding that one and two can be at the same time (on which see the rabbit-duck image below), he was persuaded that two things can only follow one another in antithetical terms.

What is alive and what is not? It depends on how things are looked at; for things can always be looked at in different ways.

(*) We use “objects” and “things” interchangeably. Cf. Heidegger, Bremen and Freiburg Lectures: Insight Into That Which Is and Basic Principles of Thinking (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), pp. 5-22.

(⦼) Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), p. 11.

(⧁) Elizabeth A. Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Durham [NC] and London: Duke University Press, 2016), p. 60.

(⊕) Steven Shaviro, “Non-Phenomenological Thought” (Speculations: A Journal of Speculative Realism 5 [2014]: 40-56), p. 50.

(⊗) Tim Ingold, Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (London and New York: Routledge, 2011), p. 32.

(⊛) “Connect with yourself” is one of the favourite slogans of today’s wellness industry. It may be a helpful motto if one is lost in the modern jungle, or traumatised due to the Daedalian qualities of the modern life; but, for all the good this slogan may do, it shows that the Other is long gone.

(⦿) Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert, The Falling Sky: Words of Yanomami Shaman (Cambridge [MA] and London: Harvard University Press, 2013), p. 3

Beautiful. Just related to your lead inquiry (Are stones really alive, though? What do we mean by saying that something is “alive?”) in this manner:

Although consciousness studies are increasing, when will our research and awareness turn attention to crystal consciousness?

In the consideration of the “subterranean lovemaking of the elements” –bear in mind a mere one thousand millionth part of our body is “physically-comprised” matter — the rest?

Fields of energy.

Very interesting, Randy, thank you!