(N.B. This entry complements our entries “Hybris Over What Is: On Aeschylus” and “Hybris’s Reverse: On Heraclitus and Pindar”)

this gleam (kosmos), the same for all things, neither the gods nor men have made it, but it always was, is, and will be an ever-living fire measuredly kindling and measuredly going out – Heraclitus, DK B30

We are used to distinguish in any verb its tense, i.e. the temporal circumscription of the action it expresses, which can be past, present, or future. Also, we are used to distinguish in any verb whether the action it expresses is complete or unfinished, hence between the verb’s perfect or imperfect aspect, respectively.

Yet ancient Greek – like other Indo-European languages for that matter – had a verbal aspect called aorist (ἀόριστος, aoristos): “without limits.” What tense or tenses correspond to them is something unclear. And while everybody acknowledges their perfective quality, everyone suspects, too, that aorists did not necessarily evoke the past. Unlike past verbs (“Patroclus climbed the wall”), present verbs (“Patroclus is climbing the wall”), and future verbs (“he will climb the wall”), aorist verbs express actions as though they were occurring now (“he climbs the wall”) exactly as they occurred once and as they will occur again whenever the action in question is evoked in the future. In other words, aorist verbs avoid to circumscribe the actions they express to any particular time (past, present, or future).

But then, can it not be said that aorist verbs – especially as they are employed in the Iliad, on which more below – reflect what the ancient Greeks called, in opposition to χρόνος (chronos) or the “passing of time” that devours all its children, αἰών (aion) the “now” which is “always,” not because it lasts eternally but because it is perfect and complete in its being, in the sense that what is expresses always-already being’s full positiveness, i.e. being’s effective fighting off the darkness of non-being? And if this is correct, would not the Iliad’s aorists (notice: 54% of its verbs) be the narrative equivalent of Calchas’s and, hence, Apollo’s vision – whose oracle Calchas (blind to the appearance of things) utters? For Homer says of Calchas that, despite his blindness, he is able to see “what is, what will be, and what was” (τά τ᾽ ἐόντα τά τ᾽ ἐσσόμενα πρό τ᾽ ἐόντα [ta t’eonta ta t’essomena pro t’eonta].(⦼): Put differently: Calchas’s vision dissolves (like Zeus’s all-powerful light, of which Apollo is but a manifestation) Cronus’s cruel dominion.

Consider, for example, Patroclus’s aristeia in Iliad 16.702-711, 783-867: it is mostly built on aorist verbs to render all the more vivid, by making them incandescent, as it were, not only Patroclus’s actions, but also Apollo’s, who put limit to Patroclus’s ὕβρις (“excess”) causing his death. Achilles’s killing of Hector in Iliad 22.247-369 is built, too, on aorist verbs. Compare, furthermore, the verbs assigned to the Dawn and to Zeus in Iliad 2.48-51: they prove that αἰών is not exclusively connected to human action, but extensive to the whole cosmos, of which the gods are but the ever-living (or, again, incandescent) forces which shine through it. Notice, lastly, the stress put on the shining qualities of being in Iliad 22.131-135 apropos Achilles’s helmet, in this case by means of a verb in the imperfect. Green translates:

Thus he [= Hector] pondered, waiting, while Achilles approached him – / the equal of Enyalios, that bright-helmed warrior! – / above his right shoulder wielding his spear of Pēlian ash, / so fearsome, while all about him the bronze now glinted / like blazing fire or the rays of the rising sun.(⦿)

Green’s adverbial choice (“now glinted”) is an excellent option indeed, as it captures perfectly the shining forth of things, and, ultimately, of Achilles, when Hector sees him for the first time, which is not a past episode, therefore, but an event that receives its aliveness from the poet’s lips whenever he sings it, as though it were untouched by the passage of time… Now!

Only this can explain why the Homeric poets’ performances where accompanied with beating feet and clapping hands on the part of the audience (⊜) – of an audience that thus displayed αἰδώς (aidos), i.e. “respectful awe” before what they listened to.

Hence we do not follow Martínez Marzoa when he affirms that aorists are “factitive” verbs – in contrast to both “cursive” or imperfect verbs and to “estative” or perfect verbs – and then underlines that they lack any “actual” dimension and must thus be viewed as evoking a “closed,” i.e. past, action.(⊗) Nor do we follow, more generally, the identification of the tense of the Greek aorist with that of a simple, indefinite past.(⦹)

Yet if the secret of αἰών can be said to lie somewhere – we should like to argue – it is in Parmenides’s Poem. For Parmenides affirms of “what is” (ὡς ἔστιν, hos estin) that “it is not born” (ἀγένητον, ageneton) and “imperishable” (ἀνώλεθρον, anolethron); hence, he adds, it can neither be said that “it has been” (οὐδέ ποτ᾽ἦν, oude pot’en) or that “it will be” (οὐδ᾽ἔσται, oud’estai) as it is “one” (ἕν, hen) “now” (νῦν ἔστιν, nyn estin) “altogether” (ὁμοῦ πᾶν, homou pan). With this, though, Parmenides does not have a spheric being in view – safe, at most, metaphorically. Rather, he is thematising one of the two sides of the dimensional difference that we mentioned in our previous post, between being’s incandescent gleaming and the ephemeral nature (read: the coming into being and passing away) of all things, which are (both) equally incontestable.

Severino’s paraphrasis of Parmenides is superb:

Being, all Being, is; and so it is immutable. But Being that is manifest is manifest as coming-to-be. Therefore (which is to say, precisely because it is manifest as coming-to-be), this manifest Being, insofar as it is immutable (and it, too, must be immutable, if it is Being), is other than itself qua coming-to-be. Or again: […] this green color of the plant outside my window is Being, and insofar as it is Being it is immutable, eternal (there is no time when it was-not or will not-be). But then, this “same” green color was born just now, when the sun began to illuminate the plant; and now, when I have moved my head and see it in a different perspective, it is already vanished. This “same” color (like the countless events that make up our experience) is therefore immutable, insofar as it is Being, and is manifest as coming-to-be. This means that the “same” (this color) differentiates itself; i.e. that qua immutable it constitutes itself as and in a different dimension from itself qua coming-to-be.

This difference, which is the authentic “ontological difference,” is implied by the fact (for indeed it is a matter of fact) that “the same” is subject to two opposite determinations (immutable, coming-to-be), and so is not the same, but different (i.e. this eternal color is not this color that is born and perishes).

[…] Everything that is present is therefore, qua immutable, different from itself qua coming-to-be. […] By this we certainly do not mean to say – nor can it be said – that the dimension of Becoming is therefore Nothing. We mean, per contra, to say that all Being, all the positive that crosses the inhospitable region of Becoming, is always already rescued from nothingness and always and forever sheltered and contained in the immutable circle of Being. All the positive, all that is positive in Becoming, is; it keeps to itself, in the “sincere land” that lacks nothing ([οὐκ ἀτελεύτητον τὸ ἐὸν] ouk ateleuteton to eon, Parmenides, Fr. 8, 32), for if anything, i.e. any positive, were lacking, then that positive would not-be, i.e., would be negative.(⊙)

Put otherwise: even if what is opposes non-being only for a while (i.e. while it is), while it does so it opposes non-being absolutely, or with all the positiveness of being, which thus admits no gradation whatsoever. In a nutshell then:

every being is eternal […] and the variation of the world’s spectacle, the appearing of variation, is the rising and setting, the showing and the hiding of the eternal.

Heraclitus does not point far from this when he writes that “the never-submerging before which one cannot hide” (τὸ μὴ δῦνόν ποτε πῶς ἄν τις λάθοι, to me dynon pote pos an tis lathoi, DK B16) “was, is, and will be an ever-living fire” (πῦρ ἀείζωον, pyr aeizoon)” whose “gleaming” (κόσμος, kosmos) all things display (DK B30). As we wrote in “The Last God,” there are two – and ultimately only two – options before it, two options before “that which is” (τὸ ὄν, to on): attempting to dominate it, i.e. displaying “excess” (ὕβρις, hybris) οver it, or, alternatively, showing αἰδώς (“respectful awe”) towards it. Such, we should like to venture, is the teaching inscribed at the very core of ancient-Greek thought. Forgetting it has lead us to the un-world we are in.

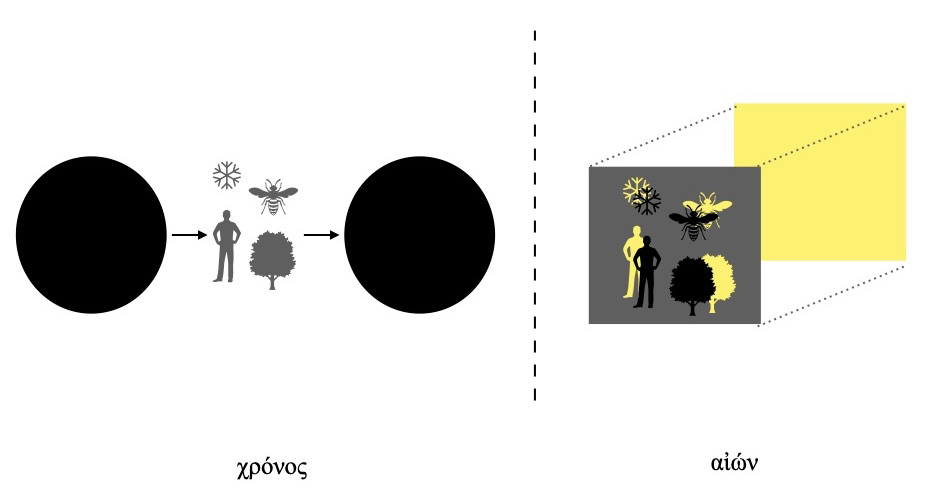

Two images of beings in time. On the left, time as χρόνος (chronos), i.e. “chronological time,” which amounts, for every being (a plant, a bee, a man, a snowflake), to the timespan of its existence, and extends, for every being, between two nothingness-es (the black circles): its former non-being (before the being in question came into being) and its future non-being (after its death or destruction). On the right, all beings comprised within the dimension of chronological time (the grey square) express the “enduring vital force” (αἰών, aion, as per Benveniste’s lucid insight) of being qua being (contained in the yellow square), in which they all partake, or, rather, which they all are while they are, which means that each being must be simultaneously viewed in two different ways, to wit, according to its ephemeral nature and according to its (simple) being. (Diagram by Polymorph)

(⦼) Homer, Iliad, 1.69-70.

(⦿) Homer, The Iliad (trans. Peter Green; Berkeley, Los Angeles, & London: California University Press, 2015), p. 403.

(⊜) On which see Eric A. Havelock, The Literate Revolution in Greece and its Cultural Consequences (Princeton & London: Princeton University Press, 1982).

(⊗) Felipe Martínez Marzoa, Lengua y tiempo (Madrid: Visor, 1999), p. 16-17.

(⦹) So e.g. Jaime Berenguer Amenós, Gramática griega (Barcelona: Bosch, 1999), p. 73.

(⦶) See especially fragment 8 (= DK B8), accessible in Greek and in Burnet’s translation here.

(⊙) Emanuele Severino, Essence of Nihilism (trans. Giacomo Donis; London & New York: Verso, 2016), p. 46-47.

(⊛) Heraclitus’s fragments are accessible in Greek and Burnet’s English translation here.

Read more here:

The Poetics of Aidos: On Pindar, Parmenides, and Bacchylides