There are two possible definitions of animism.

The most widespread one turns around notions of projection and belief. Briefly, it states that we project onto animals, plants, rocks, and natural phenomena human qualities which these things lack like, for example, consciousness, intentionality, and agency. According to this definition, set forth by Hume and popularised by Tylor, animism is an irrational, or better a pre-rational (primitive), mistake. Frazer writes: “To the savage the world in general is animate, and trees and plants are no exception to the rule. He [sic] thinks that they have souls like his own, and he treats them accordingly.” The view behind this first definition of animism is empiricist: on the one hand, there are “empirical” things that we can touch: this “tree” next to me, that “rock” over there, etc.; on the other hand, “non-empirical” counterintuitive things of which the more we can say is that they are spoken of and believed in: the tree’s “spirit,” the rock’s “soul,” etc.

Conversely, the other definition is political and, we may say, radically democratic. For it defines animism as an attempt to acknowledge life in everything, or to bring everything back to life against its Christian and modern devitalisation. In this way the world ceases to be one (ours!) and becomes what it always was in the first place: a pluriverse, with each thing having its own relevance in a multi-perspectival landscape that lacks any centre. Examples of this include coral reefs, in which multi-species alliances form transversal worlds, but also, say, the worlds of the Chambri and the Matses: the Papuan crocodile-people and the Amazonian jaguar-people, respectively.

Yet these two definitions of animism are, the first one, incorrect, and, the second one, incomplete.

The first definition is incorrect because it sees human imaginary “projections” where there is something else at stake. The second definition is incomplete because, while being overall correct and reasonable in the sense that it invites us to see beyond our nose, it says nothing about the ground on which each thing’s own perspective is rooted. Is it its “soul” or “spirit,” understood as its active principle? Such is the conclusion to which the use of the term “animism” would seem to lead: if everything is animate, is it not because everything has a “soul” (Latin: anima, plural animæ) that animates it? After all, is it not this what “animism” is about?

I would like to suggest here the opposite: that animism is, paradoxically, about the body – about the different types of embodiment to which different kinds of lifeworlds correspond. Tell me what type of body you are and I will tell you what you are able to live – or, better, you will signal it yourself. For there are as many worlds as there are bodies(*).

But I am going to leave the issue of the body for another occasion(**). Suffice it to say for now that extramodern peoples have no words like “soul” or “spirit.” These are always our words. Consequently, calling the principle of a body its “soul” or “spirit” only speaks of our limitations to grasp the thought-worlds of others – in other terms, it highlights our miserable ethnocentrism.

But let me give you a little example of this lexical asymmetry, which should prevent us from seeing “spirits” or “souls” where it is something else that demands to be paid conceptual justice instead:

As Marco Antonio Valentim observes(***), the concept of utupë among the Yanomami, which is often indistinctly translated as “image” or “soul,” denotes at the same time: (1) the “innermost part” of a thing, of which the thing is but the “copy”; (2) a “copy” of something else which is not the thing but its “ancestor”; (3) something that is inherently “many” rather than one; and (4) something that happens to be simultaneously “different-and-not different” from that of which it is the original, from that of which it is the copy, and form its many possible variations. Are you confused? Good then! Because, as you see, the original is here turned into a copy, the unique transformed into a multiple, and the same changed into the other and vice versa, following a principle of “vice-diction” (Deleuze) that allows contradictory qualities to be simultaneously expressed, as it happens with polyphonic music, rather than the Aristotelean principle of “non-contradiction” that precludes it – or the superiority of Music over Logic (****).

Do you still feel like calling it “soul”?

(*) You may know the anecdote, which Lévi-Strauss liked particularly and mentioned twice, and which Viveiros de Castro has recently recovered to illustrate his theory of Amazonian perspectivism: Upon arriving in the Antilles, the Spaniards organised inquisition tribunals to determine if the native Americans had souls, while the Taino, in turn, drowned the Spaniards in a river to check what kind of body they had (corruptible, incorruptible?). In short, the Spaniards never doubted that the Amerindians had bodies, they wanted to know if they had souls to figure out if they werefullyhuman. Conversely, the Taino never doubted that the Spaniards had souls, but they wanted to know what type of body they had, so as to figure out if they were humans or more than humans or other than humans; this is to say, humans of an altogether different kind, for their worldview is one in which most things are human, “humanity” being more a condition than a biological species for them.

(**) In the meantime, you may like to glance through my paper ”Spinoza and Savage Thought,” which elaborates, among other things, on Spinoza’s view that the mind (mens) is the idea of the body.

(***) In Extramundanidade e sobrenatureza. Ensaios de ontologia infundamental (2018), p. 220.

(****) Jankélévitch: “Only music can express infinitely ambiguous things, as, unlike logic, music must not opt between things which are incompossible or contradictory: it can bring forth and develop, with the help of polyphony, several independent lines of discourse,” including dissonant lines, we may add..

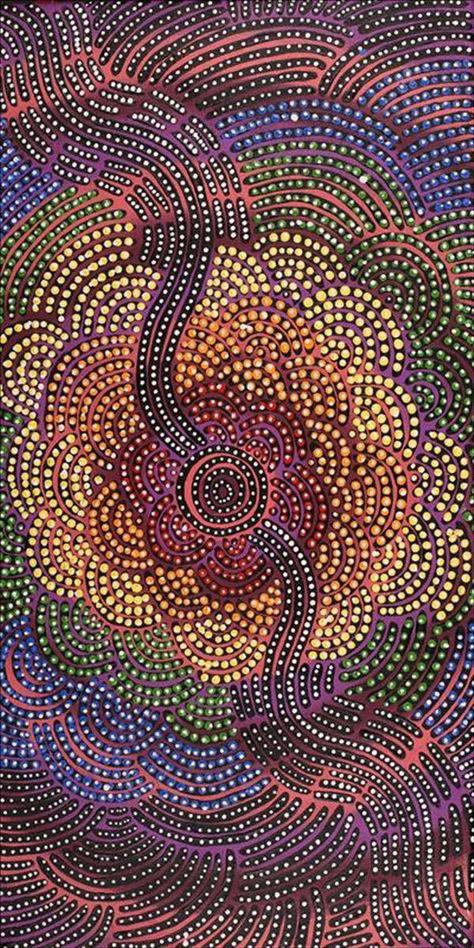

Warlpiri Flying Ant Dreaming