Pasolini’s Teorema (1968) ends with one of the characters, “Paolo,” a bourgeois middle-aged man, running naked through the wilderness out of shame, a profound anti-bourgeois shame. For, while Paolo is able to break off with the bourgeois order that he himself incarnates as both a bourgeois father and businessman, he proves incapable of replacing it with anything else. There is, though, another parallel, if often overlooked, end to the film: “Emilia”’s (i.e. the maid’s) self-burial, whose self-declared purpose is to regenerate the earth with her tears.(⚃)

There is an undeniable difference, then, between Pasolini’s “Paolo” – whom we fancy running endlessly out of social-political shame – and the Hopi chief about whom Mauss wrote: “cet homme, recordman de la course à pied, me disait: « Je peux courir ainsi parce que je n’arrête pas de chanter mon chant du feu.»”(*) In English: “this man, a running record holder, said to me: ‘I can run like this because I keep singing my song of fire all the time.’”

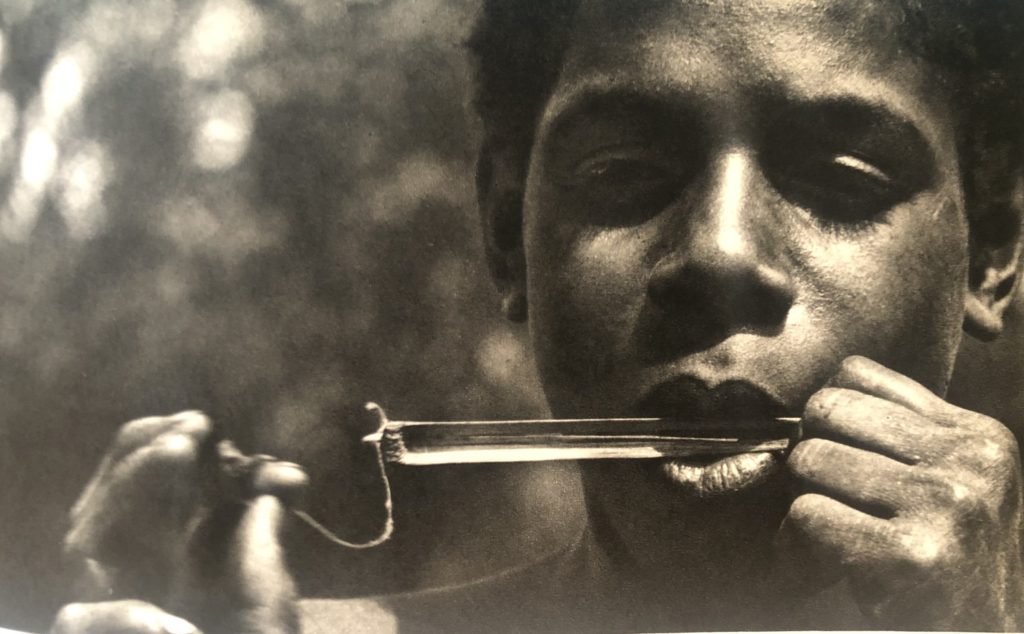

Interestingly, among the Dani of Papua New Guinea, what we would call the “soul” (or any other similar term) is called “seeds of singing” (etai-eken)(Δ). Seen from a Dani perspective, therefore, Pasolini’s “Paolo,” unlike Mauss’s Hopi chief, lacks a soul: he shouts, but does not sing.

Clearly, the emptied soul of Pasolini’s “Paolo” enacts a protest – in a way, a necessary one – against an illusorily filled soul: the bourgeois soul with its ideal possesions. And it is possible to see in the bourgeois soul a secularisation of the Christian soul, which was not-less illusorily filled with hope, i.e. with the promise of happiness as a future, if immaterial, posession. For in both cases the soul is something one needs to fill: it is one’s centre, a centre that one must either uphold above the troublesome material tentations of the body, or else satisfy by means of the accumulation of material goods that bring peace to it.

This centre-type of the soul is experiencing today a new permutation. It must still be filled, but with healthy habits (which are another type of good deeds) capable of bringing to it, if not salvation, at least wellbeing, and thereby – we are told – harmony. For, we are once more told, it is our own centre.

If Spinoza famously stated that we do not know what a body can do, or even what it can be,(#) it could be similarly argued that we do not know what a soul can be and do. Before they were transformed into peripheral neo-capitalist consumers, the Dani – like most extra-modern peoples – did.

First, their souls, which they rather call “seeds of singing,” aim at singing to the world so as to allow everything to shine forth in its being, beauty, and aliveness, which is why they are intimately connected to language. Thus in Dani culture they settle in the solar plexus only after a child acquires the ability to speak.

Secondly, their “seeds of singing” allow the Dani to sing to their own provisional aliveness before the very face of death, which men confront at war and women overstep by giving birth.

Lastly, their “seeds of singing” prompt the Dani to remember their family ghosts, and thereby to take care of them by singing their memory.(∞)

Their “seeds of singing,” write Robert Gardner and Karl Heider, are “sometimes associated with the physiological heart […]. [According to the Dani] [a]ll creatures posses this indispensable ingredient, with the exception of insects and reptiles. In humans, however, these ‘seeds’ have a significance surpasing that of all other elements of one’s constitution.” For they do not only point back to oneself and/or to one’s action-oriented engagement with the given, but propel oneself towards exteriority and, in a way, transcendence beyond what we have called elsewhere the “earth’s semiotic prism”: to sing the world in its aliveness, to boast before death’s menacing presence while assuming one’s irrenounceable mortality, and to care for those who have died and who have thereby departed from the world of the living.

(⚃) On how class differences in Pasolini are not only, and not even primarily, class differences, see our entry titled: “Capitalism as Acculturation – or, the Revolutionary Force of the Past.”

(*) Mauss, Marcel. Manuel d’ethnographie (Advertissement et préface de Denise Paulme; Paris: Payot, 1967), p. 286.

(Δ) Robert Gardner and Karl G. Heider, Gardens of War: Life and Death in the New Guinea Stone Age (Introduction by Margaret Mead; New York: Random House, 1968), p. 88.

(#) See also our entry titled: “Those Who(se Bodies) Do Not Look Like Us.”

(⊜) Gardner and Heider, Gardens of War, p. 88.

(∞) Gardner and Heider, Gardens of War, p. 88.

Paolo (Massimo Girotti) running through the wilderness the final scene of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema (1968).

Dani boy playing a bamboo mouth harp. Source: Gardner and Heider, Gardens of War, p. 73.