In a letter addressed in 1897 to Leopold Goldschmidt – who, having acquired a painting of his, Jupiter and Semele, asks its author for some comments on it – Gustave Moreau writes: “It would be deplorable if this admirable art, which can succeed in expressing so many things, so many noble, ingenious and profound and sublime thoughts, this art whose eloquence is so powerful, finds itself reduced to photographic translations or paraphrases of vulgar facts.”(*)

We would like to call the reader’s attention to the last sentence in the quotation. The art of painting should not limit itself (a) to “photograph” reality or (b) to “paraphrase vulgar facts,” says Moreau. With it Moreau does not merely express a general impression of his on what painting should notbe. His words have a specific target, or, rather, two interrelated targets.

Let’s look back at the Paris art scene in 1863. That year, two thirds of the paintings presented to the Paris Salon – which, organised annually by the Academy of Fine Arts, served to promote the artistic careers of its winners across four general genres: history painting (inclusing mythology), landscapes, everyday-life scenes, and still-life – were refused by the jury, This caused considerable unrest among many young painters and critiques, their complaints reached Napoleon III, and – willing to let the public judge by itself – the latter allowed by imperial decree the rejected paintings to be exhibited at the Palace of Industry in what soon came to be known as the Salon des refusés (Exhibition of Rejects).

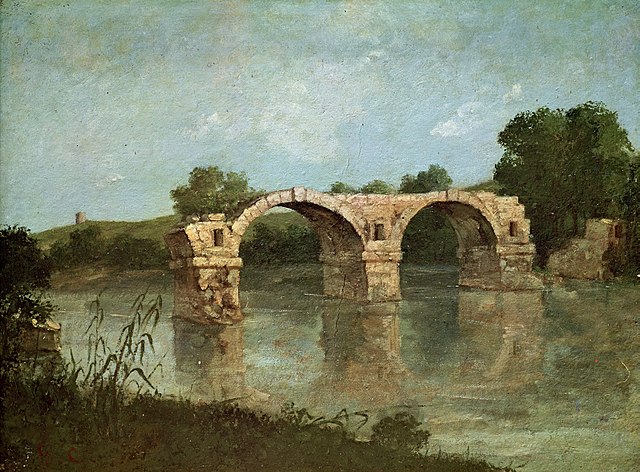

Among the painters whose works were rejected by the jury of the 1863 Salon, two are worth mentioning here: Courbet (who presented to it Le retour de la conférance [Return from the Conference]) and Manet (who presented for his part Le déjeneur sur l’herbe [The Luncheon on the Grass]). Courbet was the champion of pictorial “Realism.” We reproduce two of his paintings below.(∆)

Courbet, Le Pont d’Ambrussum [The Pont Ambroix] (1857)

Courbet, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon et ses enfants en 1853 [Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and His Children in 1853] (1865)

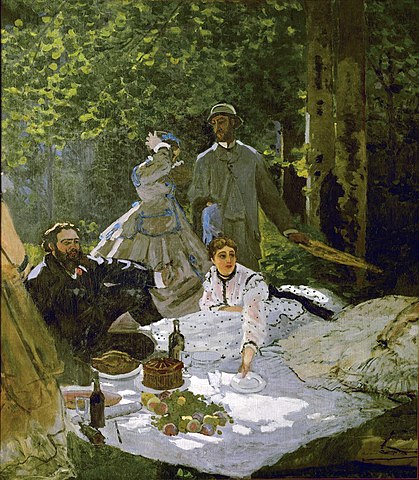

As for Manet, whose “direct translations of reality” Zola famously praised and who gained extraordinary prominence at the Salon des refusés of 1863, he would little by little gather around him a group of painters who, from 1874 onwards, would come to be known as “impressionists.” These drew their inspiration from Turner’s atmospheric qualities,(⦿) from Corot and the Barbizot “Naturalists,”(∅) from Courbet, and from Manet himself. Compare, for instance, Manet’s aforementioned Le déjeneur sur l’herbe (1863):

with Monet’s homonymous painting from 1865–1866 (which portrays, among others, Courbet lying on the grass):

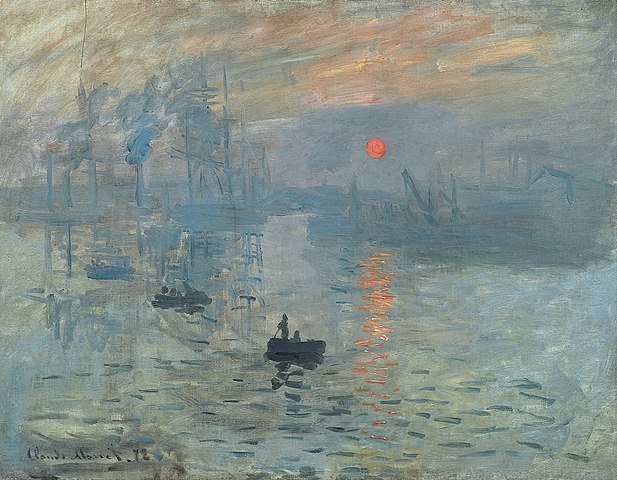

When one thinks about the French Impressionists, one tends perhaps to think, first and foremost, of Claude Monet’s Impression, soleil levant [Impression, Sunrise] (1872), which was in fact the painting that, in 1874, led the art critic Louis Leroy to (ironically) coin such term (which had been formerly used by Daubigny and Manet in connection to their own works) to describe the pictorial style (unsatisfactory in his view) of a number of then young painters like Degas, Morissot, Pissarro, Renoir, and Monet himself.

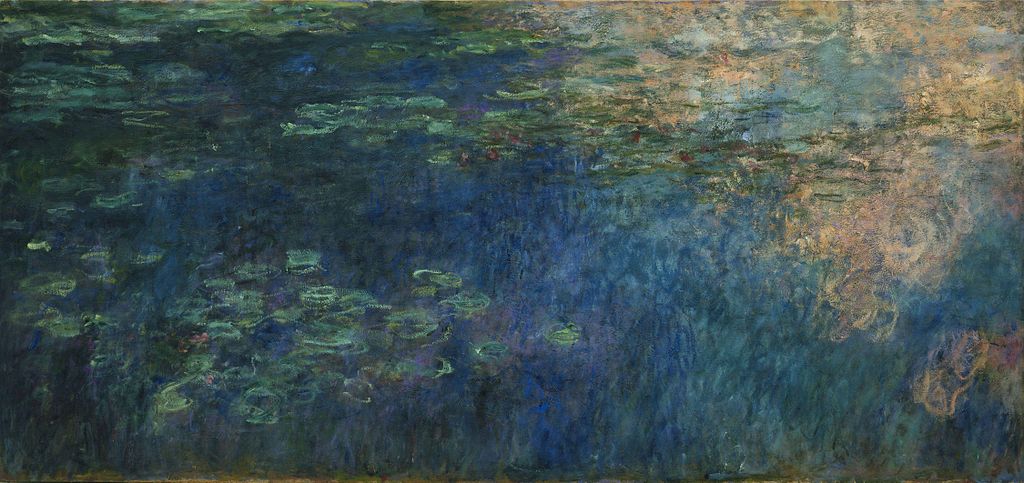

Alternatively, one tends to think of Monet’s Water-Lilies series (1890s–1920s), in which light and chromaticism are everything – and abstraction, arguably, far more than a presentiment.

(c. 1915)

(c. 1925)

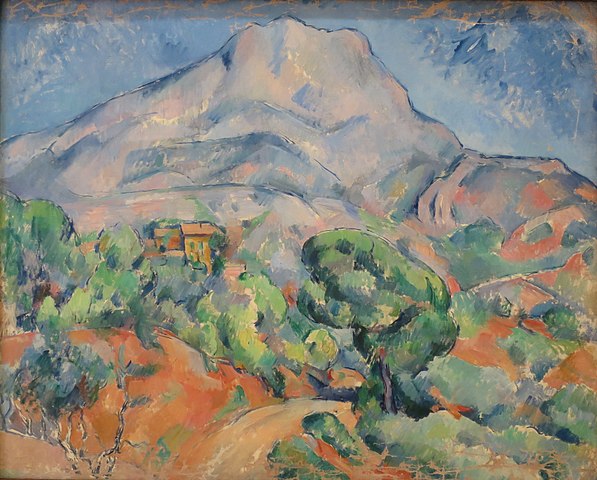

There is something equally impressive in some of Monet’s early paintings and in most of his late paintings: reality is transfigured in them by an inner force that makes it implode and overflows through it. In other words, in such paintings Monet paints the way in which reality is carried away and metamorphosed by the spirit – a spirit which is colour and light in Monet, colour and matter in Cezanne:

Cezanne, Route de la Montagne Sainte-Victoire [Road to the Sainte-Victoire Mountain] (1898–1902)

Heraclitus’s words are thus applicable to a good number of Monet’s and Cezanne’s paintings: “Here, too, the gods dwell.” For it seems as if in such paintings matter, and colour, and light take occasional form qua water lilies, or qua mountain. Interestingly, both Cezanne’s series of Sainte-Victoire Mountains and Monet’s Nymphaeaceae series include almost numberless paintings which oftentimes vary only slightly from one another, depending; it is as though Cezanne and Monet painted once and again the same motif (Cezanne’s apples are another example of it) to unravel a secret present both within and beyond the visible, hence capable of experiencing infinite manifestations while remaining always unique.

But French Impressionism – in which Cezanne does not exactly belong, as he is more of a Post-Impressionist – is not just Monet’s sunrise and water lilies. There is something else in it as well; or, rather, something else to begin with, in respect to which Monet’s paintings often represent a deviation – or, what amounts to the same, a beautiful excess.

French Impressionism is also this:

Degas, Musiciens à l’orchestre [Orchestra Musicians] (1872)

and this:

Renoir, Le déjeuner des canotiers [Luncheon of the Boating Party] (1880–1881)

Put differently, Impressionism is – to use Moreau’s own words – a “paraphrasis of vulgar facts” (read: of ordinary facts). It can be objected that many of the elements in the three paintings reproduced above (notice e.g. the effect of the wind in the canopy and the bushes in Renoir’s painting) are alive in them to a point that rules out “vulgarity” of their style. Indeed. Monet’s Sur les planches de Trouville [The Boardwalk on the Beach at Trouville] (1870) goes even further in this sense, for the whole scene seems to be the very effect of the wind.

Notice, nonetheless, that Moreau denounces less a vulgar art than an art, no matter how exquisite, which paraphrases “vulgar facts,” i.e. ordinary facts – those facts characteristic of an emergent social class that, indifferent to any aristocratic grandeur but unconcerned at the same time with the social inequality brought about by economic exploitation, takes delight in the enjoyment of its own little pleasures (a promende through the beach, a coffee in the afternoon, a soirée at the concert hall, etc.). Hence, while academicism bore upon it the Romantic values of the higher social classes (read: of the aristocracy and, in its image, the high bourgeoisie), and Realism was favoured instead by socialist painters like Courbet (although, of course, not all Realists and Naturalists were, like him, socialists), Impressionism glimmered mostly as a petty-bourgeois art.

Yet, on account its dsmissal of narrativity and its attentiveness to ordinary facts, Impressionism can be legitimately seen as the continuation of Realism and Naturalism – which attempted to “translate” reality in primarily “photographic” terms(⚃) – by other means.(∞) For, however diverse from them, it shares with them the substitution of immediate sensorial perception (no matter how arduous expressing it faithfuly might prove) for academicist narration. Thus, like Realism and Naturalism, Impressionism shows preference for the everydayness of life over and against the singularity of the events of history (whether ancient, medieval, or modern) and the different corpora of myths (Biblical, Greco-Roman…) on which academicist art (its orientalist côte aside) focussed instead.

Consider, for example, this painting by Cabanel:

Cabanel, La mort de Moïse [The Death of Moses] (1850)

The Impressionists would reject both its formal classicism and its narrative qualities – as well as its pedagogic, edifying purpose.

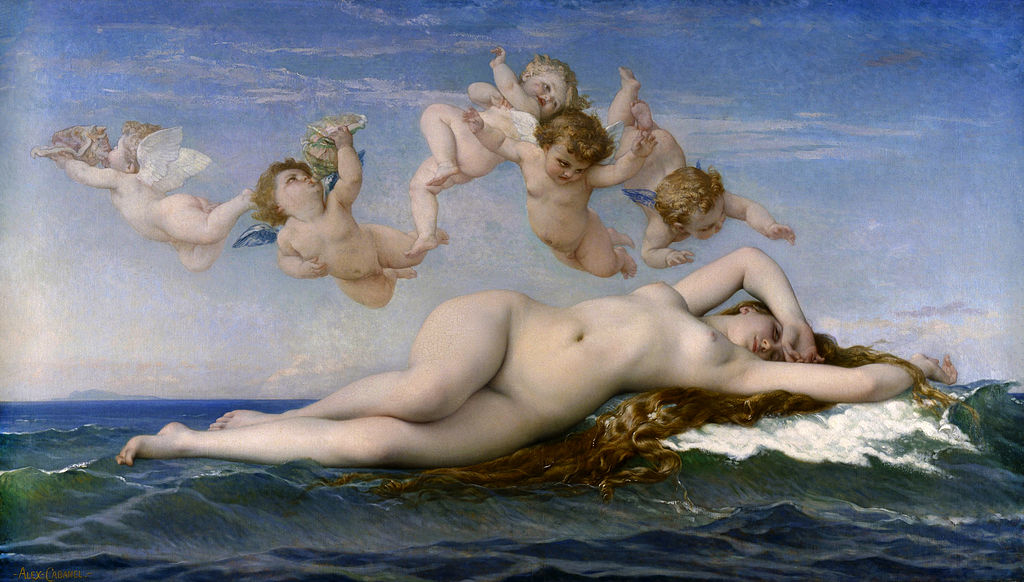

Moreau, too, from the very beginning of his artistic career, aimed at breaking with all of it. Compare, for instance, Cabanel’s Birth of Venus:

Cabanel, La Naissance de Vénus [The Birth of Venus] (1863)

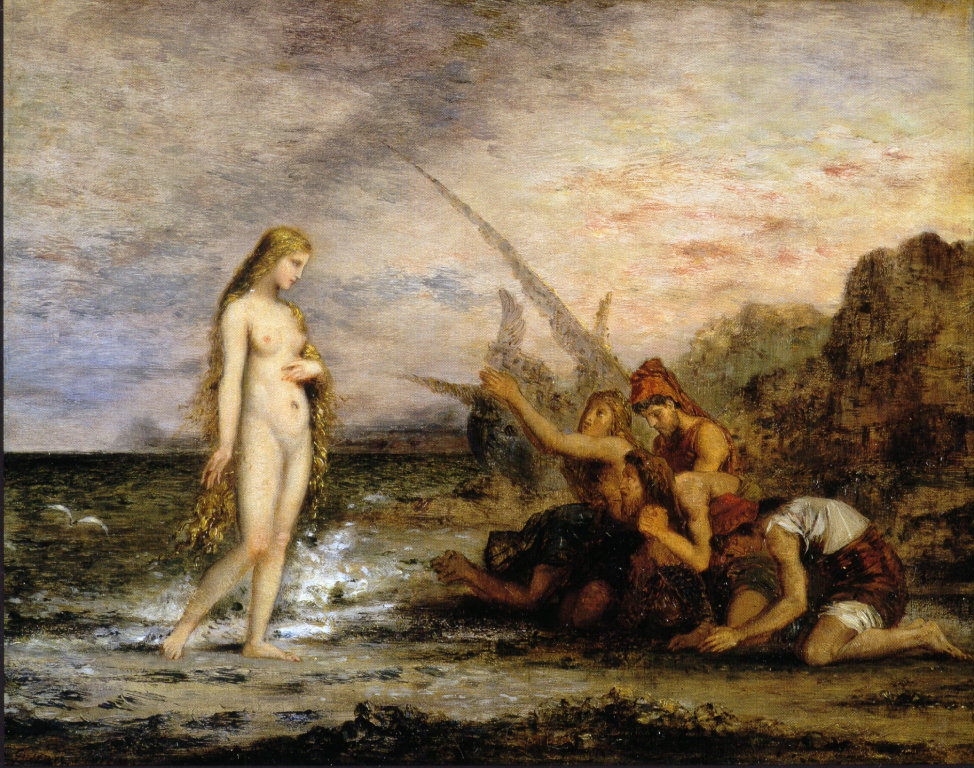

and Moreau’s:

Moreau, Vénus et les pêcheurs [Venus and the Fishermen] (c. 1866)

This is one of Moreau’s earliest paintings. Formalism sucumbs in it to poetry, narrativity to magic. The admixture of poetry and magic is distinctive of Moreau’s style. It does not only help him to re-establish what is known as “history painting” on an altogether different basis: it allows him to explore the secret correspondences between life and death, word and silence, desire and loss, the soul and the earth…

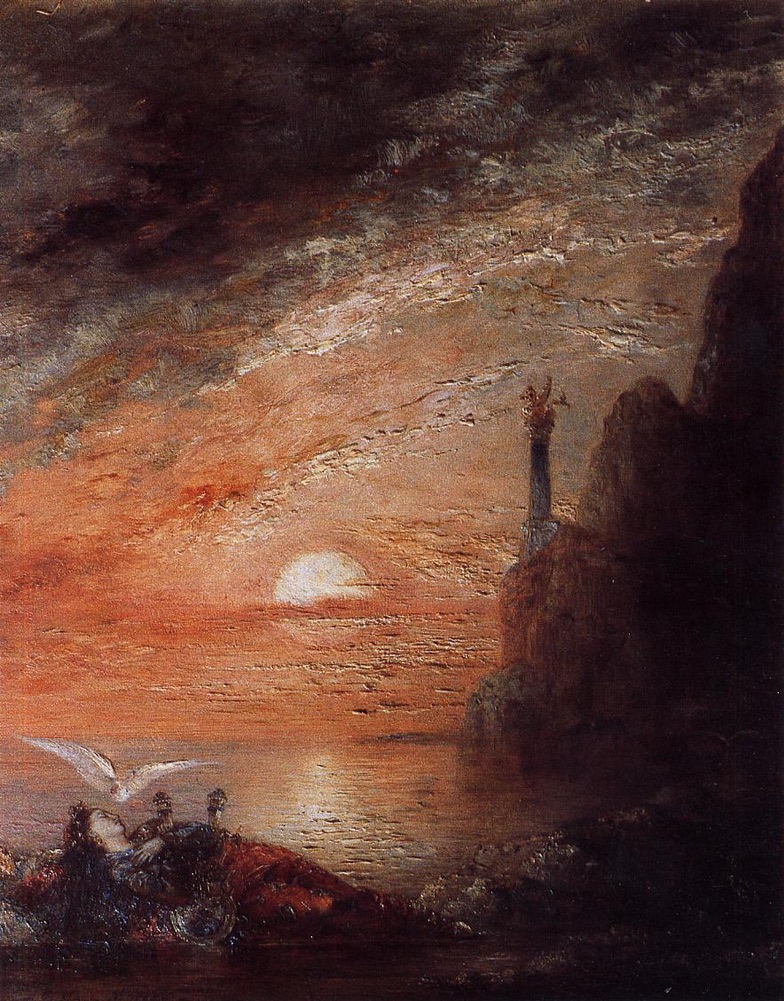

Moreau, Mort de Sapho [The Death of Sappho (1872–1876)

Moreau, Hélène à la porte Scée [Helen at the Scaean Gate] (1880–1885)

Moreau, La fiancée de la nuit [The Fiancée of the Night] (c. 1892)

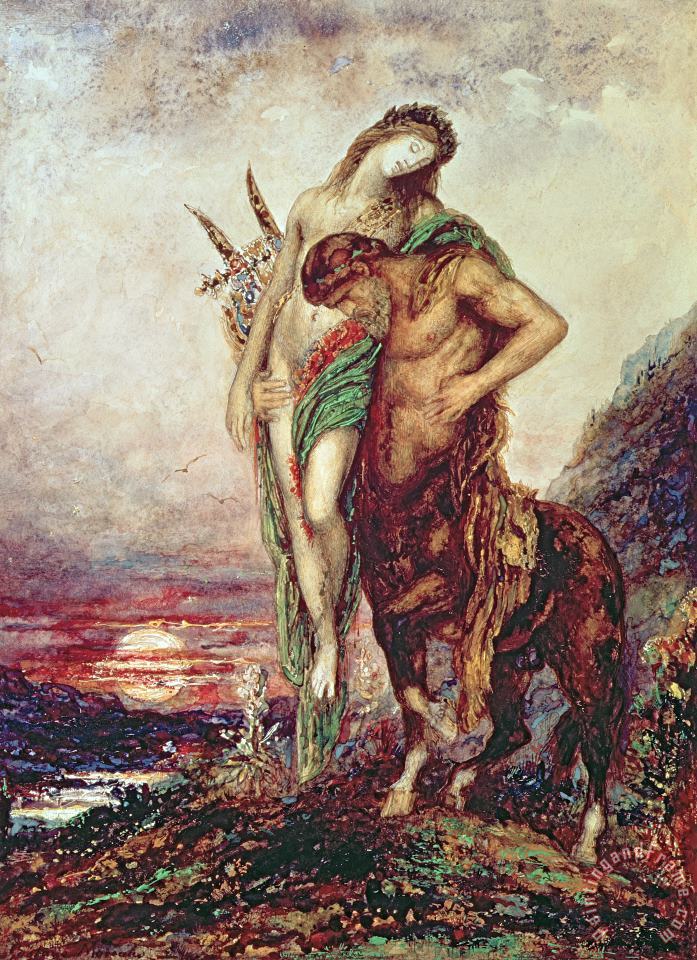

Moreau, Poète mort porté par un centaure [Dead Poet Borne by a Centaur] (c. 1890)

If, in Monet, the spirit becomes colour and light, as we have underlined, in Moreau – whose colourfulness is bewitching – it acquires visibility to interrogate its own depth. “Traveling on every path, you will not find the boundaries of soul by going – so deep is its measure,” Heraclitus said. There is no room here for luncheons by the riverside or on the grass.

(*) Quoted in Geneviève Lacambre, Gustave Moreau. Maître sorcier (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), p. 99 (emphasis added).

(∆) All images below are in the public domain.

(⦿) On which see, e.g., Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838 (1839).

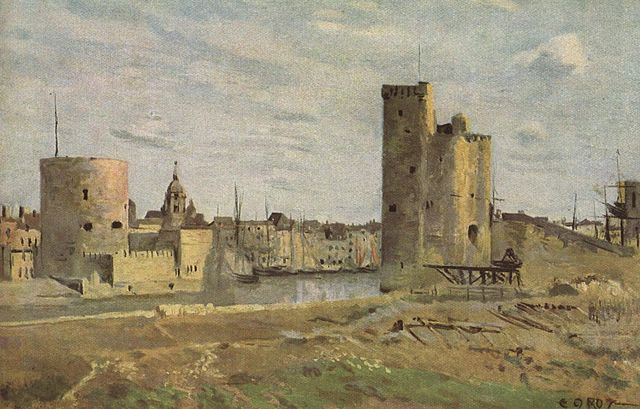

(∅) Consider, e.g., Corot’s La Rochelle, entrée du port [La Rochelle, the Harbour Entrance] (1851).

(⚃) Compare e.g. Corot’s painting in the previous note and Daguerre’s 1838 daguerrotype of the Boulevard du Temple in Paris: