I

In the introduction to his 1812 Wissenschaftslehre (WL), Fichte writes:

[…] Reality consists in the fact that our [noetic] seeing becomes invisible; here, conversely, it becomes visible.” “Hence,” he had formerly declared, “the difficulty of the WL: its task is to make visible what is commonly invisible to our consciousness – it thus sets forth a way of seeing which is contra natura but which thereby enlarges the domain of what is visible to us. (Fichte 1971, p. 324, my translation hereinafter)

It is an admirable text, extremely concise and precise. Further on, in what looks like a wink to the terminology employed by Fichte in his first WL of 1794–5 – a terminology that from 1804 onwards he would modify without this implying, though, a shift from one subject matter to another{1} – we read:

It is the fact that I think that makes patent the very possibility of this reflection (Reflexion). […] [Put differently,] the I is the universal representative of its apparition (Erscheinung) [or image (Bild), as Fichte calls it repeatedly throughout the text]. Yet, in this way thought announces itself as a mere schema (bloßes Schema), not as [a substitute for] reality, although it seems to dispense with the latter, or what amounts to the same, to cause doubt and uncertainty [namely, towards what we take to be real, i.e., towards the object of any representational or ‘factual’ (Faktisch) knowledge, as Fichte labels it elsewhere in the text]. (Fichte 1971, pp. 324–6)

“How, then, can nihilism – i.e., the destruction of reality – be avoided?” asks Fichte contra Jacobi (ibid., p. 325; cf. the ref. to Jacobi on p. 344), but taking heed of Jacobi’s main objection to transcendental idealism, as it is expressed in his 1799 Sendbrief to Fichte. “By viewing thought,” he responds, “qua pureapparition [or emergence (Entstehung), as it is called in the fragmentary WL of 1813], as a mere schema (once again: bloßes Schema) that relies somehow on reality]” (ibid., p. 326). Therefore,” Fichte goes on to say, “reflection must be pursued to the end: even though it suppresses reality at first, it [then] supplies its own antidote” by conferring upon thought, one may venture, epistemological status; for thought’s reflective Darstellung (ibid., p. 322) is no Vorstellung (cf. Thomas-Fogiel’s remark in Fichte 2005, p. 40, n.1). Hence, says Fichte, “the WL is [but a name for] the complete achievement of such reflection [which is based on a single ‘intuition’ (Anschauung)] beyond any factual constraint” and that amounts to thought’s self-“transparency” (Durchsichtigkeit) and “clarity” (Klarheit) (Fichte 1971, p. 319).

One is tempted to superimpose here Heidegger’s concept of Lichtung, although deprived of any ontological trimmings; for as Fichte puts it in the WL of 1813, the WL is no Seinslehre, given its pure epistemological status: “transcendentaler Idealismus ist absolute Aussonderung des Seins,” he writes therein (Fichte 1971, p. 4). Yet, I should not like to focus here on Heidegger, who discussed mostly Fichte’s first WL in 1929 (Heidegger 1997), i.e., in a time in which he was concerned above all by the problem of human finitude. There is surely much to say about Fichte and the late Heidegger. Here, however, I should rather like, first, to place Fichte’s reflection on thought’s self-transparency between those of Plato (in books VI and VII of the Republic) and Wittgenstein (in the Tractatus and in a letter to Russell which predates the publication of the Tractatus by, roughly, two years); secondly, I should like to briefly explore the possibility of picturing Fichte’s thought in structuralist terms.

II

How do we know and how do we know that we know? There is no other question in Plato. Thus, whereas Plato’s εἴδη supply an overall response to its first half (how do we know?), the oft-overlooked distinction in Ph. 100e–102e between the εἴδη as situated predicates or empirical concepts and the εἴδη as abstract concepts supplies, in turn, a partial response to its second half (how do we know that we know?); additionally, the introduction of pure concepts in Soph. 254d–255e completes the response to the second half of the question. And so we have that if X is determinable through predication (X is Y, which does not only mean that Y is said of X but that X appears as Y), predicates, in turn, are determinable by means of the abstract concepts they express; for its part, introducing the distinction between that which is determinable and that which determines it pushes the question on how we know that we know a step further.

It is, nonetheless, in Rep. 517a-c (at the beginning of Book VII) and 509b-c (at the end of Book VI) that Plato supplies a fourth and final response to this latter question (how do we know that we know?) that crowns, so to speak, all previous responses to it. Rep. 517a-c suggests that our ideas are possible, in the first place, because of the idea of τὸ ἀγαθόν, which, similar to the sun in the domain of the visible, stands as the condition of possibility of the eidetic domain as such, in the sense that for anything to be known as, e.g., “mortal” or “immortal,” a “triangle” or a “conic section,” a “jaguar” or a “tick,” it must meet to begin with the condition of being meaningful, thinkable, and knowable, and thereby “good” (in contraposition to that which is neither knowable, nor thinkable, nor meaningful, and hence confusing or bad). Moreover, in Rep. 509b-c, Socrates famously tells Glaucon: “not only do our objects of knowledge owe their being known to that good [read: to the very notion of meaningful thinkability or, put the other way round, to the very notion of thinkable meaningfulness ] – the same,” he remarks, “stands for their being [read: for their being such and such, a ‘conic section,’ a ‘jaguar,’ etc.],” for which reason, Socrates goes on to say, τὸ ἀγαθόν must be assumed to be “beyond being” (ἐπέκεινα τῆς οὐσίας). Inevitably Glaucon interprets that Socrates endorses the view that there is some-thing beyond being – hence, his laugh, which, being perfectly aware of the enigmatic nature of his own affirmation, Socrates accepts. In rigour, then, τὸ ἀγαθόν is no-thing other than its pure “difference” vis-à-vis what there is (Hyland 2006, p. 20), for it is, simply, the condition of possibility of thought as such – like Fichte’s Klarheit.

III

What Fichte hints at by means of an intuition, and Plato by recourse to an enigma, Wittgenstein cautiously approaches as a paradox. Consider the following propositions of the Tractatus (which I give in Pears & McGuinness’s translation [Wittgenstein 1961]):

2.1 We picture facts to ourselves.

1.1 The world is the totality of facts, not of things.

1.13 The facts in logical space are the world.

2.02 A picture represents a possible situation in logical space.

2.172 A picture cannot, however, depict its pictorial form: it displays it.

2.174 A picture cannot, however, place itself outside its representational form.

Propositions 2.172 and 2.174 question the possibility of depicting what might be called the horizon of meaningful thinkability that I have mentioned in the previous section: the invisible behind the visible, to keep with Fichte’s terminology, or, what amounts to the same, the unsaid behind the said which is, though, the condition of possibility of the said (cf. Wagner 2019, pp. 19–57).

Now, is not the problem of the said and the unsaid beneath the said the problem that articulates, if variously, the Tractatus and the Philosophical Investigations? – the Philosophical Investigations in terms of what particular “language game” (Sprachspiel) supplies meaning to a given proposition; the Tractatus in relation to the difference between the “said” (gesagt) and the “shown” (gezeigt), on which Wittgenstein wrote to Russell on August 19, 1919: “Now I’m afraid you haven’t really got hold of my main contention, to which the whole business of logical prop[osition]s is only a corollary. The main point is the theory of what can be expressed (gesagt) by prop[osition]s […] and what cannot be expressed by prop[osition]s, but only shown (gezeigt); which, I believe, is the cardinal problem of philosophy” (Wittgenstein 2008, p. 98).

“Reflexivity” or “self-referentiality,” then, as Isabelle Thomas-Fogiel labels it in her two studies on Fichte (Thomas-Fogiel 2000, 2004) and her two essays on contemporary philosophy (Thomas-Fogiel 2005, 2015); or “meaning,” as Sofya puts it in turn (Gevorkyan 2022) in conversation with Thomas Sheehan’s (2015) reinterpretation of Heidegger – such may well be the cardinal problem of philosophy, after all.

IV

Allow me to draw a quick cross-reference here to Althusser’s early texts, in particular Lire le Capital and Pour Marx, where, like Plato and Fichte, he plays (literaly!) with the dialectics of the “visible” and the “invisible” – in this case, with the notion of the “problematic” that, in any text, remains “unsaid” behind what is “said” in it and which, he says, can only be reconstructed through a “symptomatic reading” of the text in question that accounts for its “relation” with its own “object” (Althusser & Balibar 1970, pp. 11–69) and where he emphasizes the need that any philosophy therefore has to “put its object to the test” by “putting itself to the test of its object” (Althusser 1969, p. 38). This brief reference to Althusser – who, it can be argued, restablishes as the condition sine qua non of theoretical consistency Fichte’s own demand for concordance between Tun and Sagen (on which see, e.g., Fichte’s discussion of Spinoza in the WL of 1812 [Fichte 1971, pp. 326–8]) – will now help me to re-position Fichte’s thought in the proximity of structuralism.

As I argue in Segovia 2022b, pp. 512–13, what structuralism sustains is that, given two elements: A and B (e.g., “langue” and “parole” [Saussure], “consanguinity” and “affinity” [Lévi-Strauss], etc.), they are susceptible of being interpreted as forming a structure when and only when A proves to be what it is inasmuch as it differs from B, and vice versa, when and only when B proves to be what it is inasmuch as it differs from A – their co-implied difference being their structure, i.e., the meaningful relation that determines their individual qua joint being.{2} Consequently, a structure in the structuralist sense is not exterior to, and hence does not transcend, its elements or terms, but names their difference. Hence, too, Althusser’s notion of a structure’s “immanent” causality, according to which a structure is immanent in its terms and solely present in its effects (Althusser & Balibar 1970, p. 187); in other words, a structure is no more, but also no less, than a thinkable relation of reciprocitybetween two given elements.{3}

In fact, Fichte’s distinction between what shifts from visibility into invisibility and vice versa (reality [A] and thought [B], respectively) operates upon an identical premise. For their difference can be described like a shift in the focus – which takes places at the B-level – from one to the other; in short, then, A and B stand in a relation of inverse proportionality. Plus, their being thus brought together as each other’s reverse (or multiplicative inverse) does not erase their difference, quite the opposite: it only serves to highlight it. Lastly, the fact that it is only from B’s self-reflective perspective that B and, ultimately too, then, A become visible in their difference, hints at the fact that their unity and their difference is purely thinkable – or a “mere schema,” to quote Fichte again, who thus adds an interesting twist to Parmenides’s definition of “thought” (νοεῖν) and “being” (εἶναι) qua τὸ αὐτό.

V

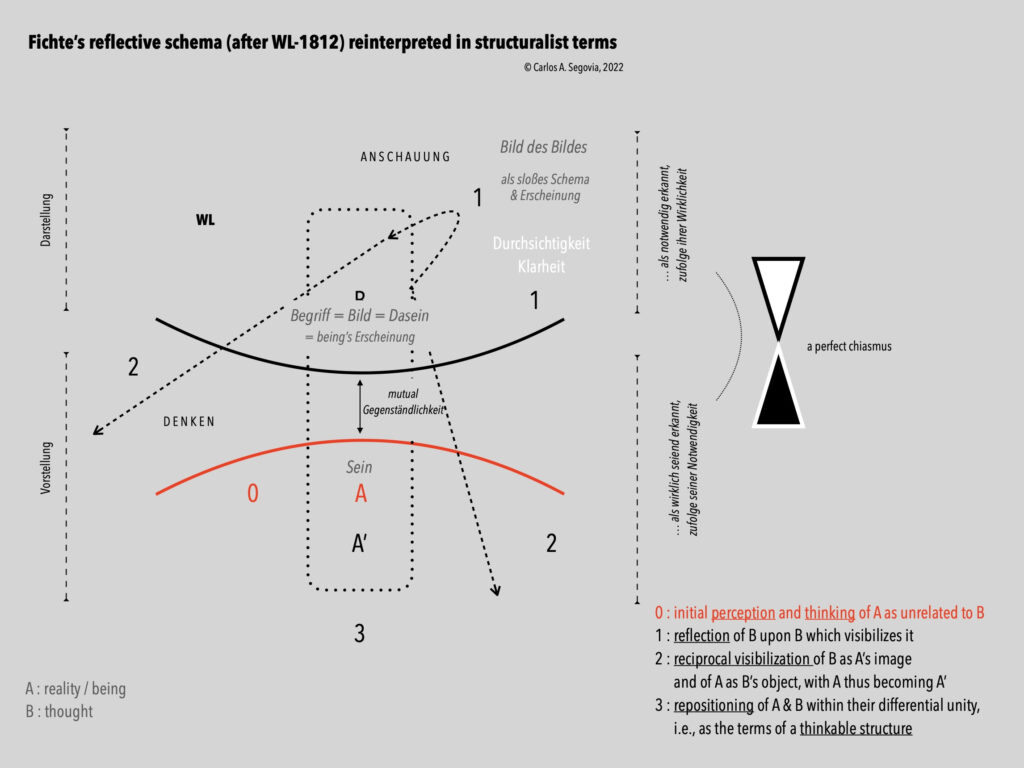

It is possible, I think, to diagram Fichte’s dissymmetrical correlation between reality and thought{4} as follows:

Following Spinoza’s distinction between “extension” and “thought” (Spinoza Eth., II, 1 & 2; cf. Fichte 1971, p. 327), on the lower side (A) we have “being” (Sein) – which, says Fichte, is “known” in its “reality” or “effectivity” (Wirklichkeit) because of being “necessary” (notwendig) (Fichte 1971, p. 333) and is that which “thought” (denken) posits as its “object” (Gegenstand) (ibid.) Conversely, on the upper side (B) we have the “concept” (Begriff), which is also being’s “image” (Bild) and hence its “apparition” (Erscheinung) elsewhere (ibid., p. 332) or “being-there” (Dasein) (ibid., p. 333){5} – and which, says Fichte, is “known” in its “necessity” (Notwendigkeit) because of being “real” or “effective” (wirklich), which means that its necessity on account of its “form” (Form), since thought is ontologically “contingent” (zufällig) (ibid.). Notice the perfect chiasmus or inverse proportionality. Furthermore, whereas the A-level is delimited as such by our thinking, Fichte goes on to say, the B-level can only be apprehended with recourse to our “intuition” (Anschauung) (ibid.) – their dissymmetry becomes once more patent at this juncture. For its part, “reflexivity,” which is the domain of the WL proper, involves a four-stage process that can be deduced thus (cf. ibid., pp. 327–8, 332–3, 337–42, 345): there is, at the outset (0), the perception and the thinking of A as being entirely unrelated to B, which remains “invisible” at that initial stage; then occurs (1) the “reflection” of B upon B, which visibilizes B by producing “an image of the [concept-]image” (ein Bild des Bildes) as an “apparition” on its own; next (2), the reciprocal visibilization of B as A’s “image” and of A as B’s “object” – with A thus becoming A’ and A’ and B positioning themselves as each other’s “counterpart” (Gegenstand) – takes place; accordingly (3), A and B are repositioned in their differential unity as the terms of a thinkable structure.{6}

Notes

{1} Pace Rivera de Rosales 2016, p. 97. On the polyvalence of Fichte’s terminology, where a single idea is often diversely conceptualized, while other times a unique term or expression is used in different ways, cf. Breazeale 1998 (which examines Fichte’s manifold use of the term Anschauung in his earliest writings) and Thomas-Fogiel 2004, pp. 63–4 (which surveys Fichte’s ongoing rewording of his fundamental intuition that “the understanding is absolute self-intelligibility, [i.e.], reflexivity [Reflexibilität]” [Fichte 1971, p. 6]).

{2} See further Segovia and Shaikut Segovia 2023, where we apply this definition of what a “structure” is to the unity of “earth” and “world” understood as their thinkable difference (in terms of inverse proportionality), on which see also Gevorkyan and Segovia 2021; Segovia 2022c.

{3} Cf. Maniglier’s (2006, p. 460) reinterpretation of structuralism as a philosophy of difference.

{4} On their dissymmetry, see further Segovia 2022a.

{5} Interestingly, in his 1795 essay on the I as the principle of philosophy (Vom Ich als Prinzip der Philosophie), Schelling employs the term Dasein to designate the “existent” (as Heidegger would do in Sein und Zeit) and claims contra Fichte that it is with it, rather than with the notion of reflexivity, that philosophy ought to begin (Nassar 2020, p. 241). Here (in 1812), Fichte employs here Dasein in an altogether different sense: there is, on the one hand, being, he suggests, but then there is thought as being’s “there” or as the “there” of being, where being “appears” to us.

{6} For the terms in the diagram unmentioned in this brief commentary (namely, Schema, Durchsichtigkeit, Klarheit, Darstellung, and Vorstellung), see supra, section I.

References

Althusser, Louis (1969): For Marx. London and New York: Verso.

Breazeale, Daniel (1998): “Fichte’s Nova Methodo Phenomenologica: On the Methodological Role of ‘Intellectual Intuition’ in the Later Jena Wissenschaftslehre.” Revue internationale de philosophie 206, pp. 587–616.

Althusser, Louis, and Étienne Balibar (1970) Reading Capital. London: New Left Books.

Fichte, Johann Gottlieb (1971): Fichtes Werke, vol. 10: Die Wissenschaftslehre (1813), Die Wissenschaftslehre (1804), Die Wissenschaftslehre (1812), Das System des Rechtslehre (1812), ed. Immanuel Hermann Fichte. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Fichte, Johann Gottlieb (2005): Doctrine de la science. Exposé de 1812, trans. Isabelle Thomas-Fogiel in collaboration with A. Gahier. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Gevorkyan, Sofya (2022): “Meaning, That Demonic Hyperbole.” Polymorph Minor Essays. Available at: https://polymorph.blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Polymorph-Minor-Essays-3.pdf

Gevorkyan, Sofya & Carlos A. Segovia (2021): “Earth and World(s): From Heidegger to Contemporary Anthropology.” Open Philosophy 4, pp. 58–82. Available at: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/opphil-2020-0152/html?lang=en

Heidegger, Martin (1997): Gesamtausgabe, vol. 28: Der deutsche Idealismus (Fichte, Schelling, Hegel) und die philosophische Problemlage der Gegenwart, ed. Claudius Strube. Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann.

Hyland, Drew H. (2006): “First of All Came Chaos.” In Heidegger and the Greeks: Interpretative Essays, ed. Drew H. Hyland & John Panteleimon Manoussakis. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, pp. 9–22.

Maniglier, Patrice (2006) : La Vie énigmatique des signes. Saussure et la naissance du Structuralisme. Paris: Léo Scheer.

Nassar, Dalia (2020): “An ‘Ethics for the Transition’: Schelling’s Critique of Negative Philosophy and Its Significance for Environmental Thought.” In Schelling’s Philosophy: Freedom, Nature, and Systematicity, ed. G. Anthony Bruno. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 231–48.

Rivera de Rosales, Jacinto (2016): “Die Welt as Bild.” In Johann Gottlieb Fichtes Wissenschaftslehre von 1812: Vermächtnis und Herausforderung des transzendentalen Idealismus, ed. Thomas Sören Hoffmann. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 97–108.

Segovia, Carlos A. (2022a): “Εἶδος⧹Utupë – Or Yet Another Take on the Dissymmetric Reciprocity of the Real and the Symbolic.” In Langage, interprétation, représentation : perspectives pluriculturelles, transhistoriques et interdisciplinaires, ed. Fionn Bennet & al. Reims: Éditions et Presses Universitaires de Reims, pp. 63–95 (in press).

Segovia, Carlos A. (2022b): “Guattari⧹Heidegger: On Quaternities, Deterritorialisation, and Worlding.” Deleuze & Guattari Studies 16(4), pp. 508–28. Available at: https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/dlgs.2022.0492

Segovia, Carlos A. (2022c): “Rethinking Dionysus and Apollo – Redrawing Today’s Philosophical Board.” Open Philosophy 5(1), pp. 360–80. Available at: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/opphil-2022-0209/html?lang=en

Segovia, Carlos A. & Sofya Shaikut Segovia (2023): Dionysus and Apollo after Nihilism: Rethinking the Earth–World Divide. Leiden & Boston: Brill (in press). [https://brill.com/display/title/63363]

Sheehan, Thomas (2015): Making Sense of Heidegger. London & New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Thomas-Fogiel, Isabelle (2000) Critique de la répresentation. Étude sur Fichte. Paris: Vrin.

Thomas-Fogiel, Isabelle (2004): Fichte. Réflexion et argumentation. Paris: Vrin.

Thomas-Fogiel, Isabelle (2005): Référence et autoréférence. Etude sur le thème de la mort de la philosophie. Paris: Vrin = The Death of Philosophy: Reference and Self-reference in Contemporary Thought, trans. Richard A Lynch. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

Thomas-Fogiel, Isabelle (2015): Le lieu de l’universel. Impasses du réalisme dans la philosophie contemporaine. Paris: Seuil.

Wagner, Roy. The Logic of Invention. Chicago: HAU Books, 2019.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1961): Tractatus logico-philosophicus. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1961.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig (2008): Wittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents 1911–1951, ed. Brian McGuinness. Oxford: Blackwell.