The word “evolution” has some unpleasant connotations. For example, it is thought that evolution works by progressing from less complexity to more complexity, with human exceptionalists arguing that the perl of both evolution and complexity are we: humans.

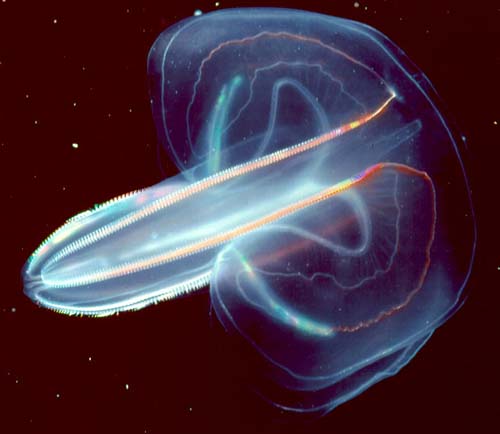

I have discovered that contemporary biology proves otherwise by reading Andreas Hejnol in Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet, a beautiful volume recently edited by Anna Tsing in collaboration with other biologists and environmental anthropologists that posits critical and creative tools for survival in our times of ecological collapse. Hejnol shows that life becomes complex only when it needs to. If a holobiont—that is to say, an interspecies assemblage, which is what most so-called organisms are(*)—needs to change, it does so according to its needs. But it ignores the human laws of progress. If it needs to decrease its complexity to adapt to its current environment, it will do so, as gelatinous ctenophores (see the image below) show, for instance.

Life diversifies itself like the waves in the sea. As a true artist it does not obey laws according to which its variations ought to be produced. Unconstrained by anything but itself, it freely explores its limits. The word “evolution” says nothing of life’s freedom and creativity.

In contrast, the expression “vital exploration,” which I take from contemporary Butō master Jonathan Martineau, opens to our eyes an ocean of ever-differing, non-linear waves. And in this ocean, where hierarchy has no place, humans are just one wave among others.

Further reading: Anna Tsing et al. (eds.), Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet (2017)

(*) The term “organism” is viewed today as problematic by many biologists, since organisms are generally thought of as being enclosed in themselves, which is never the case. Most organisms are holobionts to the extent that they are sympoietic.