This is a post on life and love as portrayed in the poetry of Omar Khayam; and, additionally, on a major difference between the spiritual worlds of Iran and India.

Allow me to start by saying that, unlike many Westerners since Anquetil-Duperron had the Upanishads translated in the 18th century, I have never had the least interest in Hinduism, or in Buddhism for that matter(*). And let me add that, unlike many fellow Spaniards, I have never been moved by Andalusian Islam either. My Orient was always, and still is, a radically-different one: Persia, that is, Iran.

I first went into the Persian thought-world reading Omar Khayam. Then I travelled to Iran and wrote two philosophical essays, one on Molla Sadra Shirazi, the other one on Avicenna. And now I am preparing a book on Saadi’s poetry. Whatever I have done over the past years, then, I have done it while keeping an intermittent eye on Persian poetry, philosophy, and music. And here am I, back again into Khayam, who, moreover, was a poet, a philosopher, and a musician.

There is a rubai (or quartet) of his(**) which reads:

برگیر پیاله و سبو ای دلجو

فارغ بنشین به کشته زار و لب جو

بس شخص عزیزرا که چرخ بدخو

صد بار پیاله کرد و صد بار سبو

That is to say (my translation):

Take gently the cup and the jar

and sit down freely at the orchard by the stream;

of so many dear people has the evil wheel

made a hundred times jars, and a hundred times cups!

By “evil wheel,” the poet means the inexorable succession of life and death which no-one can escape, as all the living die, and although new lives do then emerge, these, too, are painfully condemned to pass.

In India, the suffering that this ongoing exchange between life and death provokes is often avoided through the practice of detachment. Nothing lasts; therefore, one should free oneself from one’s outer and inner attachments alike. In other words, suffering can only be overcome if one renounces to establishing any links, which are always by nature illusory; and for this to be possible, one must stop desiring. A dispassionate attitude is, then, the secret to avoid pain.

This dispassionate attitude does not entail removing oneself completely from the world. It demands relating positively to it without establishing any preferences between whatever comes our way or withdraws from it – and without rejecting anything either. It implies, we could say, living in the world without depending on it, as an itinerant Hindu asceticist or Buddhist monk would(***).

Lastly, uniting oneself with the anonymous principle of life which is thought to lie behind every life-form without being enclosed in any of them, is the final goal of this way of life. All suffering will be gone then. When the time of your death comes, you will not feel that you die but that you transform instead into something else and equally living, if impersonal. In short, unbecoming or transcending who you are is here the means and the end of a truly-spiritual life.

This is unacceptable in Iran. You are in life (though for a brief period of time!), and while you are alive as yourself, you are in the domain of light (if, again, for a short time). Undoubtedly, the wheel of time will break you and destroy you, but while you have not yet been destroyed you must affirm life and sing to it, living that present, living that moment to the fullest. That is why Khayam writes: “sit down freely at the orchard by the stream” (my emphasis), this is, free of any concerns and fears. The chosen place is also relevant: “at the orchard by the stream” (again, my emphasis), which means there where life is fresh and fruitful. Rather than that of an itinerant monk, the ideal human type here is that of a poet – and a drunkard.

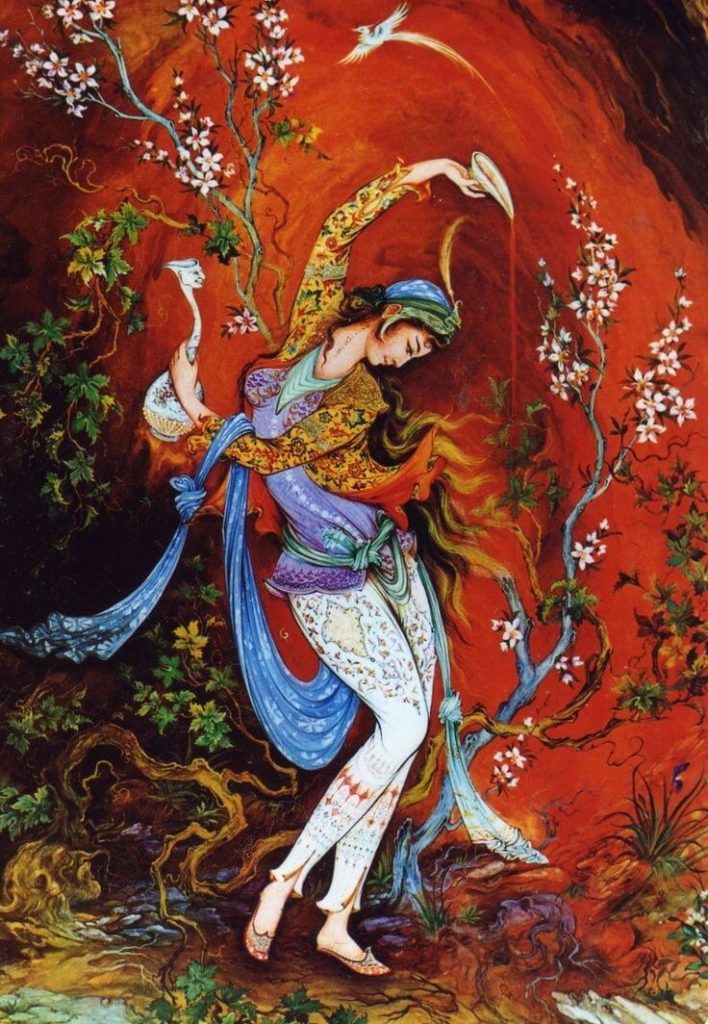

For here and elsewhere in Khayam and other Persian poets, the “jar” and the “cup” refer to wine – wine, liquor, and drunkenness being in Persian poetry a frequent metaphor for “joy.” Immanent joy, or joy achieved here and now, to be more exact. But not in the sense of surrendering to the present in a sort of blind flight that would dispense us from caring for anything at all. Khayam is a poet, not a punky writer. What helps us live the present to the fullest is love, he suggests. Thus the recurrent heterosexual poetic motif in Khayam’s rubaiyat of a woman pouring wine, as in the image below – despite the fact that there is no difference in Persian language between the third person masculine and feminine, which is extremely interesting from an homoerotic perspective, in turn.

But why love, anyway? Because love pushes us beyond our solitude and concerns bringing happiness to our hearts, thus transforming life into joy and making it the more intense – and hence the more affirmative as well. Such, at least, is the Persian passionate understanding of the opportunity that love opens for us (on which see more here). And for it to grow, love demands as much devotion as it demands care.

“Take gently the cup and the jar…,” sings Khayam. For what are they made of? They are made of the bodies of earlier lovers and beloved ones, all of whom lived, loved, and then became – like we all will one day – the dust out of which all clay is made. The evil wheel of time contrasts in this way with another wheel: the wheel of love and lovers, which sings to life while life lasts – which is life’s song.

Therefore, whereas in India the issue is primarily to avoid suffering, in Iran it is to chant life; and whereas in India the means to avoid suffering is to empty oneself from any desire, in Iran love is the means to affirm life.

(*) See further J. J. Clarke, Oriental Enlightenment: The Encounter Between Asian and Western Thought (London & New York: Routledge, 1997).

(**) Although the wording at the beginning of line no. 3 may not be from Khayam himself. My gratitude to Majid Javadi for calling my attention to this detail.

(***) Cf. the similar idea expressed in John 17:16 and 2 Corinthians 10:3. Maybe this is why Indian-inspired thought proves so very attractive to many Westerners: it somehow connects with their Christian background, even when they are unaware of it – or especially in that case!

Image: Saghi (“wine-pourer”), contemporary Persian miniature by Mahmoud Farshchian

بسیار خوب و مفید . سپاس از آقای کارلوس

شما مهربان هستید متشکرم

So many thanks to Carlos and khayam