The coming of the Cosmos into being is not only a present-day scientific concern, but also a recurring object of thought. From the Babylonian Enuma Elish and numerous indigenous cosmogonies to the Big Bang theory in contemporary physics and Félix Guattari’s concept of Chamosmosis – to only mention a few examples – it has never ceased to suscite questions and approaches of different sorts. And mythology and philosophy combined may still have much to say today about what the world is, as we hope to show in what follows.

Writing in the second half of the 18th century, Heyne already underlined that myths often reflect the same ideas that, in the last instance, philosophy elaborates on. Certainly one cannot ignore Heyne, or Schelling for that matter, as it is in Schelling’s philosophy of mythology that the early study of myth reached its earliest highest peak in Europe, before reaching another one in the 20th century with Lévi-Strauss – who, like Schelling, albeit in a different way, viewed myth as thought and pushed thought into the thinking of myth.

Take, for instance, Hesiod’s poem, whose “narrative,” for the sake of simplicity, we will divide into five stages, and which we want to read philosophically not to find out what the Ancient Greeks themselves thought, but what they give philosophy to think-with, since philosophy must always think-with in order to think-on – and think-on we must today in connection, among other things, to cosmopolitics and gender.

Stage 0 – Chaos

First there is Chaos (the Open in the sense of the totally undetermined, rich in possibilities but lacking consistency). Chaos’s two children are Night and Darkness, who, in turn, give birth to other likewise obscure figures (gods and goddesses) including, among others, Death, Sleep, Misery, Mockery, Discord, Oblivion, Deceit, Sorrow… and Destiny.

Stage 1 – Feminine Autopoiesis

Then – without being begotten, since the neutral Chaos cannot beget – Gaia (the earth, mother of all the living) forms itself. This is, in fact, the only occasion in which Hesiod does not use the expression “from X, Y was born.”

Gaia’s auto-poetic (spontaneous and self-creative) emergence amounts to a First Opening – we will come across another three, successively – which, nevertheless, does not yet bring forth a fully configured world. For the world cannot come into being all of a sudden and ready-made.

From Gaia the mounts of the earth in turn raise. Then Uranos (the sky) comes forth from her, as well.

Notice that there is no superiority of the sky over the earth here, rather the opposite, even if the earth needs of the sky to produce, as we shall immediately see, something like a proto-world.

Next, from Gaia and Uranos qua first couple a first set of gods and goddesses (a first set of worldly powers, rather than mere objects) is born: the Titans.

Stage 2 – A Proto-World

Second Opening. With the Titans, the world acquires its first, if still too-basic, traits.

The Titans represent a first, not-fully conscious, configuration of the world – a proto-world made of Time, Movement, Shining qualities, etc. Each Titan symbolises one of the components of this proto-world.

Let’s not forget, though, that, apart from the Titans, and in contrast to them, a former set of gods and goddesses is still there: the children and grandchildren of Chaos, which must be viewed as counter-worldly powers. (They will always be there indeed. Put otherwise: they are always here and are here to stay, whatever the degree of configuration of the world.)

Let’s go back now to Gaia and Uranos’s offspring. Cronus and Rhea are among their offspring – hence they are two Titans.

And with Cronus and Rhea a new stage in the gradual making of the world begins: a kind of powerful, if still-latent or not-fully assumed, movement towards a higher degree of consistency that paves the way to another, further, stage in the process that goes from Chaos to Cosmos.

Stage 3 – The Dynamics of the World in Motion

Third Opening, then; one of which Cronus is somehow protagonist.

For with Cronus’s rebellion against his father Uranos (an episode whose meaning we cannot examine here), the inception (the seed) of the world as we now know it starts to take shape, given that everything (there is actually no exception to this rule) must have a beginning in order to be – thus the figure of Cronus, who symbolises countable time.

Likewise, in order for things to come into being, movement is needed – thus the parallel figure of Rhea.

Stage 4 – Possibility, Potency, and Being

A Fourth Opening vectorises itself next.

Cronus and Rhea have six children (three male gods and three female goddesses): Hades, Poseidon, Zeus, Hestia, Demeter, and Hera. And just like Cronus had formerly rebelled against Uranos, Zeus, in turn, rebels against Cronus’s ambition to keep the world in its proto-state, that is, against the fatal disempowerment and devouring of the worldly fruits by the eroding passing of time.

Hades (I), Poseidon (II), and Zeus (III) symbolise the three phases or moments – in rigour the three inherently-related forces – of something that Schelling calls das Urereignis, the Primordial Event: the full becoming of the world into being(*). We are willing to call it Chaosmosis: the fulfilled coming-out-of-Chaos of the world, which reaches its climax – and therefore its final stage – when Zeus subjugates his father Cronus and imposes himself to his brothers.

Let’s now look at I, II, and III separately, as Schelling interprets them:

I. Hades amounts to the pure, blind(**), possibility of being;

II. Poseidon to its overflowing, un-contained (wild) self-affirmation: it is pure potency lacking form and intelligence;

III. Zeus symbolises being, hence full determination… at last.

Poseidon is also Dionysos – pure emergent life. But neither he nor Hades beget children, with the exception of Triton in Poseidon’s case. Therefore, Zeus alone is father of all other Olympian gods, who symbolise variations of his light – save Aphrodite, who was earlier born out of Uranos’s emasculation by Cronus, and, eventually too, Hephaestus, who Hesiod says was conceived by Hera on her own, and Ares, who Homer portrays as being Aphrodite’s counterpart (we shall explore these exceptions in another post). Plus Zeus is also father of the human race. He is father of both mortals and immortals, then. For “what is can be said in many ways” (Aristotle), mortal and immortal being two of such ways.

But Chaos’s children and grandchildren cannot be ruled out from this world either. Night, Darkness, Death, Deceit… they are here to stay, as we have earlier suggested. They do not only surround the world from without, but infiltrate into it and menace it from within. And the Olympians are helpless against them.

It must also be emphasised, at this juncture, that Hesiod’s poem is not about things past but about things present. For the world is what it is and will keep being it as long as it keeps coming forth as what it is by means of the dynamic combination of three forces: pure possibility, potency (that is, not-yet-determined-affirmation), and determination (or being) – symbolised by Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus, that is. Chaosmosis, then, not as past event, but as an ever-renewed event.

Care and the Feminine Divine as a Counterpart to the Main Chaosmic Forces… for the Cosmos to Be There

Yet, as we have said, the children of Cronus and Rhea are six, three brothers and three sisters. Hestia, Demeter, and Hera bring stability to the world in contrast to the pure activity of its male forces. They do not seem to be part of the processual chaosmic process itself: they establish themselves in the cosmos as those who guard and care for its limits against its otherwise-excessive, insensitive forces. Therefore, they are anything but consort deities:

I’. In contrast to Hades’s inhospitality – his allotted region of the Cosmos, the underworld, cannot be inhabited by the living: it is where the dead go – Hestia is the goddess of domestic life: of the habitable.

II’. In contrast to Poseidon’s too-wild and thus formless, sterile traits due to him being pure potency – his portion of the world are the deep waters of the sea capable of raising with violence – Demeter appears as the goddess of fertility and agriculture.

III’. Lastly, in contrast to Zeus’s multifarious and uncontrolled determination – throughout the vastness of the living world – which makes him prompt to father everything so that everything may come into being (thus his numerous sexual intercourses), Hera is the goddess that takes care of that which is born.

These three feminine dimensions are not passive at all: they delimit the forces symbolised by Hades, Poseidon, and Zeus, thus making the world complete. Therefore, if Sherry Ortner once famously asked herself whether in most societies, both past and present, “female is to nature what male is to culture,” we are tempted to affirm that, in this case, it is the feminine that stands as culture vis-à-vis the savage masculine(***).

In short, without these feminine goddesses there would be an incomplete Cosmos, since the Cosmos demands limits and care.

Further reading: Hesiod, Theogony.

(*) Or, as the Neoplatonic philosophers have it, προόδος (procession).

(**) As Plato notices, Ἄιδης (Haides, Hades) ≈ αἐιδές (aeides), that is to say, invisible – literally, lacking εἶδος (eidos) or visible aspect.

(***) For which reason we cannot but dispute too Donna Haraway’s (and other eco-feminists’) claim that rethinking the earth – which we surely must today – implies recovering its sacred feminine qualities against the masculine qualities of all sky gods. This claim makes sense against Biblical phallocentrism, in which a masculine god determines the world’s being, imposes his extra-cosmic law over it, produces his own male image to rule it, and judges and punishes the rebellion of the feminine against it all. Greek as well as indigenous mythologies present a more complex and richer picture, however. And perhaps it is about time we fully overcome Christianity, instead of positioning ourselves in its outside. For, as Louis Althusser once wrote, “it is impossible to leave a closed space simply by taking up a position merely outside it: so long as this outside remains its outside, it still belongs to that closed space, as its ‘repetition’ in its other-than-itself.” Besides, to objections of the type: “But are Hestia, Demeter, and Hera not too-much linked to the household, anyway?, and does this not reflect the fact that, in Ancient Greece, women were generally confined to their homes” – we respond: Yes, yes, we know that!, but, as suggested in the outset, our purpose here has less to do with clarifying Ancient-Greek data than with thinking-with-and-beyond Ancient-Greek mythological ideas, and to do so in philosophical terms. To make it plain, then: as philosophers, rather than historians or cultural critics, we reclaim our right to try to broaden in new ways the horizon of today’s thought – by rethinking, in this case, two often-overlooked aspects of the feminine-divine in Ancient-Greek mythology: its autopoietic character (Gaia) and its fundamental cosmological role (Hestia, Demeter, Hera).

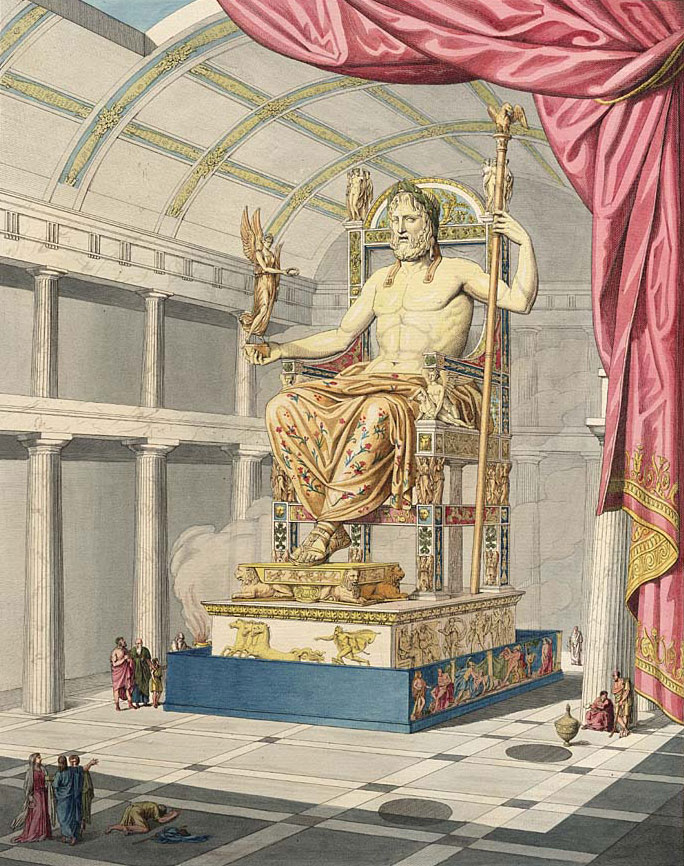

Image: Phidias’s Statue of Zeus (c. 435 BCE) at the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, as fancied in 1815 by Antoine-Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy