PREVIOUS PART HERE

From Plato to Foucault

The late Foucault – the Foucault of The Care of the Self, published only a few days before his death in 1984 – goes back to a notion which is not very different from Plato’s notion of σωφροσύνη (sophrosyne, “soundness of mind”), about which we wrote in our previous post.

The Care of the Self is the third volume of Foucault’s History of Sexuality. Foucault examines in it the ethics of the Hellenistic period in connection to the usage of pleasures, analysing thereof recommendations of austerity regarding sexual practice, sexual relations outside the marriage, and love for boys which seem to go far beyond than any earlier Ancient-Greek advice on such issues, but which can be seen, nonetheless, as a continuation of the ethic of sophrosyne. And he remarks that such recommendations have nothing to do with later Christian moral suspicions and prohibitions, since they are based on the convergence of “nature and reason” at the service of an ethics of the “care of the self” (ἐπιμέλεια ἑαυτοῦ, epimeleia heautou). The book concludes thus:

Thus, as the arts of living and the care of the self are refined, some precepts emerge that seem to be rather similar to those that will be formulated in the later moral systems. But one should not be misled by the analogy. Those moral systems will define other modalities of the relation to self: a characterization of the ethical substance based on finitude, the Fall, and evil; a mode of subjection in the form of obedience to a general law that is at the same time the will of a personal god; a type of work on oneself that implies a decipherment of the soul and purificatory hermeneutics of the desires; and a mode of ethical fulfillment that tends toward self-renunciation. The code elements that concern the economy of pleasures, conjugal fidelity, and relations between men may well remain analogous, but they will derive from a profoundly altered ethics and from a different way of constituting oneself as the ethical subject of one’s sexual behavior.(*)

The ground on which Plato’s ethic of sophrosyne and Foucault’s epimeleia heautou stand is the strict interdependence of wisdom, freedom, and happiness: by thinking we become capable of knowing and, therefore, of living our lives in a way such that we are not unreflectively carried away by our feelings; there is no other premise for a truly happy life, as life’s vicissitudes are unpredictable and many.

On Deleuze’s Dismissal of the late Foucault

Interestingly, Deleuze remained reluctant to the late Foucault. He wrote that Foucault’s “return to the Greeks” seemed to him “extremely partial and ambiguous,” since the question of “the body and its pleasures” in Ancient Greece “was related to the […] relations between free men, and hence to a ‘virile society’ that was unisexual and excluded women.”(**)

It is a mean reading of Foucault – strangely enough, for Deleuze is often generous in his interpretations of other philosophers. More importantly, it is a reading that overlooks Foucault’s willingness to find a regulatory ideal – as Foucault himself expressed – “valid for all human beings.”(***)

Possibly, Deleuze’s feared a return to Platonism behind Foucault’s epimeleia heautou. If so, he acted unfairly, but lucidly, since, following Nietzsche, Deleuze believed the task of contemporary philosophy to be the overturning Platonism.

But, as we have underlined, Nietzsche struggled against a ghost, that is, against a distorted image of Plato. An image that had turned Plato’s insights into rigid “norms” against which one cannot but rebel, thought Nietzsche. But then again, Nietzsche’s anti-Platonism must be explained not so much against the background of what Plato wrote in his dialogues as in light of the Prussian transformation of the German philhellenic/neoclassic educational tradition – of which Platonism had been the core in the 18th century – into a massive promoter of moral conservatism, bourgeoise utilitarianism, and state values.

The Untimely

Like Nietzsche, then, Deleuze takes the overturning of Plato to be the “untimely” (unzeitgemäß), or what goes against the tide. And, like Nietzsche, he makes of the revolt against all normativity the axis around which all true philosophy must revolve. Thus Deleuze’s famous saying: “A concept is a brick. It can be used to build a courthouse of reason. Or it can be thrown through the window.”

For us, however, philosophy is neither about norms nor about their transgression. To transgress a norm means to remain captured in it, if negatively. Althusser: “it is impossible to leave a closed space simply by taking up a position merely outside it […]: so long as this outside […] remain[s] its outside […], [it] still belong[s] […] to that closed space, as its ‘repetition’ in its other-than-itself.” Instead, philosophy – as we suggested last week and as both Nietzsche and Deleuze would anyway agree – is about which ideas help us to see reality in a richer way. But this means that, above anything else, philosophy must be educational whatever philosophy may need to break off with in order to educate.

But it is not only the dialectics of normativity and revolt (or dogmatism and scepticism, as Kant said) that has put at risk both philosophy and education, which might soon become extinct species. Pragmatism has contributed its own to it. Both education and pragmatism cut any norm/revolt dialectics by the half, but with different results: knowledge and utility, respectively. Therefore, they stand in opposition to one another. Furthermore, utility is becoming today’s new norm, which leaves us with the alternative: either revolt against any norm, utility included, or education at the expense of any norm, utility, and revolt. We do not mean by this that education should not suggest rules, consider practicality into account, and oppose whatever may threaten its existence. We are just not talking here about education in general, but – in line with our two previous posts, with which this one forms a trilogy – about the Ancient-Greek educational ideal based on the equivalence of the “beautiful and [the] good” (καλὸς κἀγαθός, kalos kagathos), or καλοκαγαθία (kalokagathia), which Plato thematised in philosophical terms and on which he built his philosophy.

Which of these two options – kalokagathia or revolt, then – can be identified as “untimely” today? The fact that normativity (in the form of science), revolt (be it political, libidinal, or both), and utility (in the like of capitalist benefit, self-entrepreneurship, or consumerism) form modernity’s three concentric circles, points to kalokagathia as the answer.

A Political Note, to End with

Should anyone suspect in this an aesthetic withdrawal from politics, we would like to make clear that it is the other way round indeed. But not only because divorcing politics from education is disastrous in the long run. There is more to it. The triangulation of the beautiful, the good, the intelligible, and the desirable with which we opened our Platonic trilogy two weeks ago and that, subverting Nietzsche, we have described today as the “untimely,” makes expendable any norm inasmuch as it makes dispensable the subjection and submission of our ἔρως (eros, “desire”) to any extrinsic principle imposed on it. Therefore, it makes any form of coercive power, and hence any state, expendable as well. For it amounts to a declaration of freedom – of freedom as being the essence of all beings and the first principle of any philosophy deserving such name.

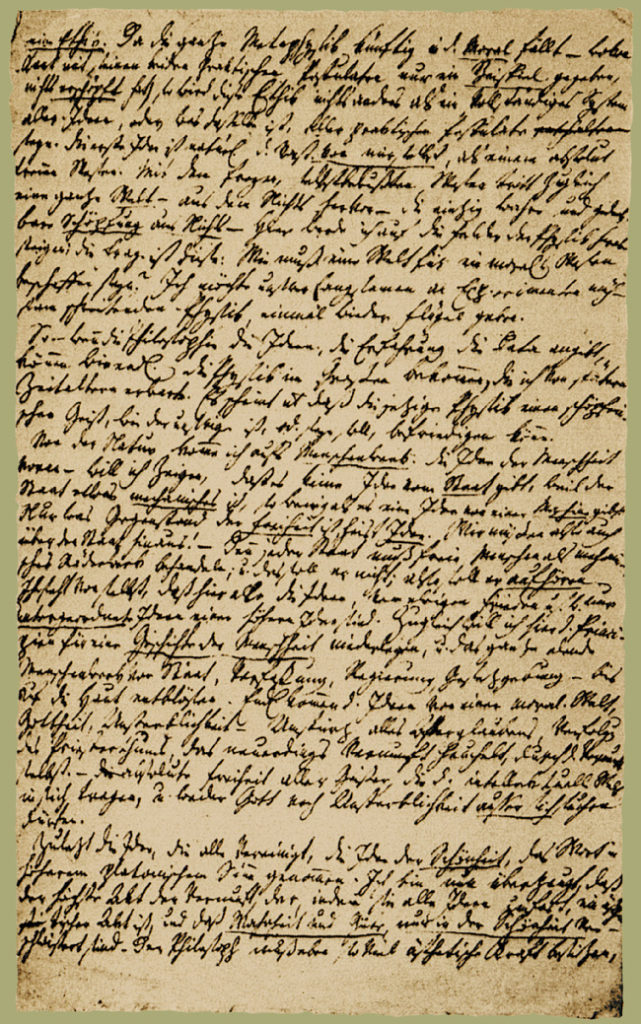

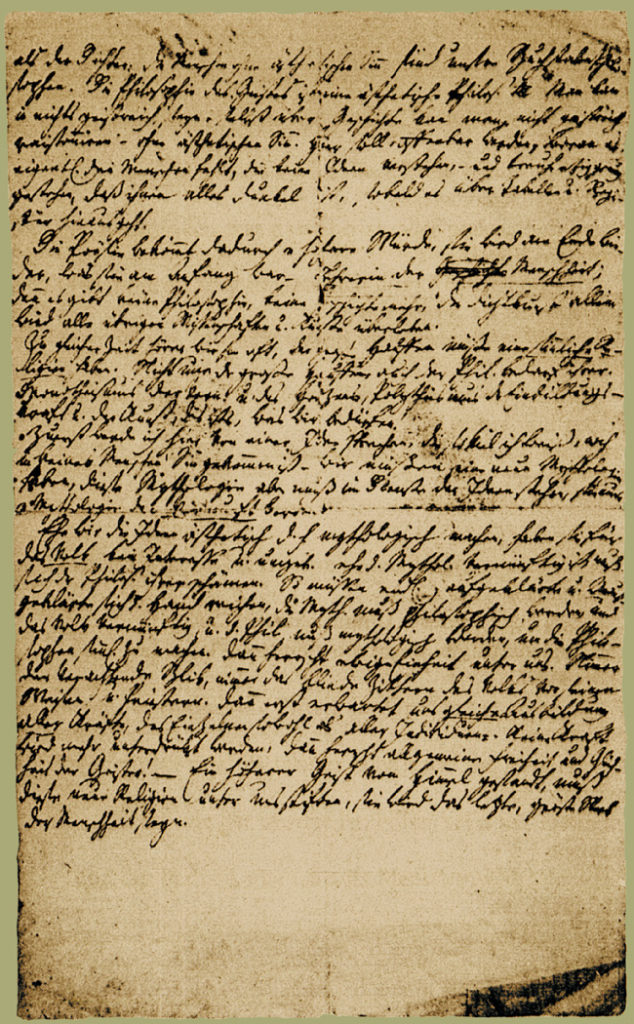

Thus, in a brief but remarkable text composed by Hölderlin around 1795 in dialogue with Schelling, which Hegel hand-copied in 1797 and has come down to us (since it was first published in 1917) as The Oldest System-Programme of German Idealism,(****) Hölderlin avows:

I want to demonstrate that there does not exist any idea of the state, because the state is something mechanical, just as there is no idea of a machine. Only that which is object of freedom is called idea. Hence, we must also move beyond the state! For every state must treat free human beings like a mechanical set of wheels; and that it must not; therefore, it shall cease to exist. […] I want […] to strip the entire miserable human construct of state, constitution, government, legislation down to its very skin.

It is a beautiful fragment that shows, moreover, that Platonism and the state are less compatible than we have been taught to think through a poor reading of Plato’s Republic – one that says more about the philosophical myopia of its readers than about Plato’s arguments and concerns.

(*) Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality (3 vols.; New York: Pantheon Books, 1978–1986), vol. 3, p. 239.

(**) Gilles Deleuze, Foucault (Minneapolis and London: Minnesota University Press, 1988), p. 148, n. 28.

(***) Foucault, op. cit., vol. 3, p. 238.

(****) It is quite remarkable because, in only two pages, it lays the foundations of Hölderlin’s philosophical poetry, of Schelling’s three consecutive philosophies (i.e. his philosophy of nature, freedom, and mythology), and of the political philosophy that Hegel’s philosophy of right would betray, so that it is possible to assess Schelling’s and Hegel’s philosophies and Hölderlin’s poetry by their proximity to and distance from the programmatic views expressed in the document.

Manuscript of the so-called The Oldest System-Programme of German Idealism (Das älteste Systemprogramm des deutschen Idealismus) in Hegel’s handwriting, recto and verso. Source: Augsburg University, Germany.