Hypercomplexity. It is hypercomplexity we are in need of in both ontological and epistemological terms—that is to say, in terms of our descriptions of what things are and of how we should study them. For we have lacked it for too many centuries, since Aristotle (and later Boethius, followed in this by the medieval Christian philosophers) offered us the oversimplified view of the world we still cling to—which is made out of four basic things, no more.

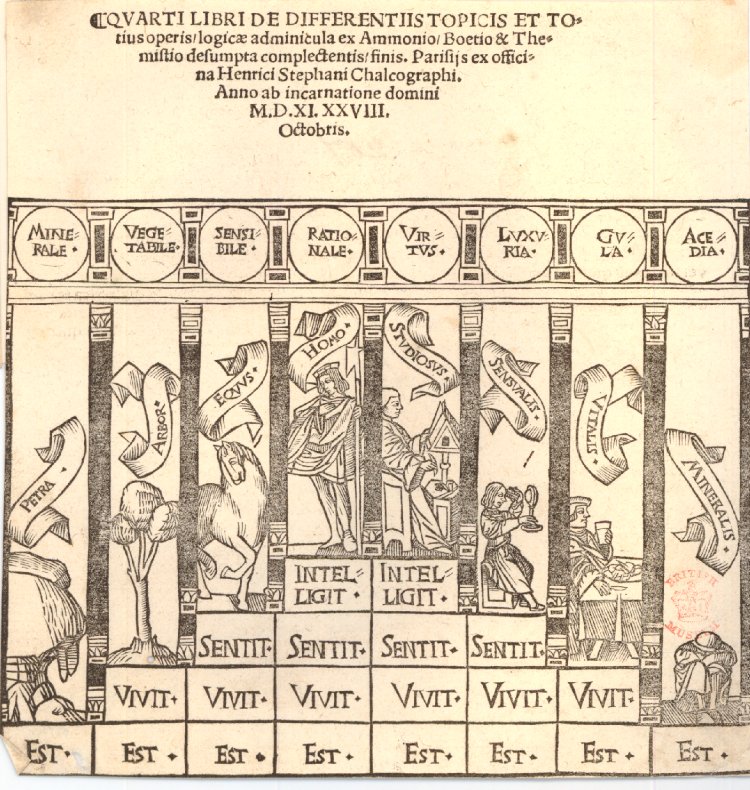

Consider carefully the following picture, which corresponds to a 16th-century Renaissance instantiation of Boethius’s natural philosophy (more precisely, of the fourfold division of its object):

“Stones” (petras, sing. petra) are assigned the lowest level of the pedestal, followed by “trees” (arbores, sing. arbor) or plants (placed one step above them), by “horses” (eqvi, sing. eqvvs) or animals (one step above these), and finally, on the top level of the whole thing, Man (homo).

Stones only “are” (on the bottom of their column it is written est,which is the third person singular of the present tense of esse, the Latin equivalent of the English verb “to be”); that is to say, they only exist. Plants exist and “live” (vivit). Animals exist, live and “sense” (sentit). Humans exist, live, sense and think or “reason” (intelligit). Such is the standard modern mainstream view of what there is in the world—a hierarchical world where humans acquire a dominant position.

But needless to say the world is different from this and much more fascinating… Let’s enchant it a little bit. In other words: let’s allow some of its hypercomplexity to surface and become apparent.

Petras

There is this an extremely interesting book by François Dagognet, Une Épistemologie de l’espace concret (An Epistemology of Concrete Space), which is unfortunately not translated into English. Among other things, it dedicates some pages to the fascinating being of stones. As Donna Haraway would have it, stones are good to think with! They merge being and non-being in themselves, as they keep memories of plants, animals, and environments that have past. Therefore, studying a stone amounts to studying what-is-no-longer inside what-is—a sort of philosophical paradox that would have made Parmenides rise his eyebrows(*). Also, stones seem to be non-living, yet the story they tell is all about life. Thus, stones present a strange admixture of being and non-being, living and non-living. Moreover, through stones time can be viewed within space. When studying rocks, one observes space (something placed in space, that is) in order to see (or reconstruct) time! Indeed, stones are beautiful poetic books, and cannot be depreciated.

Arbores

Obviously, plants do not only live but also sense (sentit) themselves and their environments. We may presume that what the authors of this picture meant is that they do not feel pain. Well, maybe they do not—but we do not know for sure. What we call pain is a reaction of animal nervous systems. Pain is a signal that something is not going well. Plants lack a nervous system. But they have other ways of managing dangerous situations, and eventually they can even fight the enemy back. Their alleged lack of pain does not mean that they are to be placed in lower echelon vis-à-vis animals and humans. They are simply different from us. You may be surprised to know that plants play, very likely see, listen to music, and think. All in their own ways, of course. You may learn more about it by reading Stefano Mancuso’s The Revolutionary Genius of Plants; you can also watch this short video by Mancuso himself here.

Eqvi

Animals do not think? Only we do—as Aristotle famously claims? Firstly, in order to pose this question and to confer it sense, in order to give it the sense it would otherwise lack, one must separate humans from all other holobionts—which ultimately we all are(**). This is already a huge problem. But moderns still perceive they must be somehow superior to every other form of life on Earth: they like to see humans in a different light, as an exception or an anomaly. A proof that people have not yet recovered from this Christian legacy is the number of New Age websites, videos, and books repeating that humans come from a different galaxy or that they are the descendants of a great civilization created by super-intelligent extraterrestrial beings. Many moderns dissatisfied with Christianity want to escape modernity through different channels like Buddhism or paganism, and “reconnect with nature” by using natural medicines and living outside the cities, still cannot accept the fact that, although humans can adapt to different environments, and build their own, they are a part of this planet and have evolved together with all other living beings on Earth, above which they do not stand. Back to our question now: animals do not think? In fact, they do—they are self-conscious, can feel empathy, make calculations, and even plan ahead. Carl Safina’s Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel is a very recommendable reading in this respect.

You and Me?

If we, humans, are unique in any possible way, it may just be because we use a type of language which is symbolic, which allows us to adapt to different environments, build, rule, and destroy. But all other animals also have their own semiotics, that is to say, all other animals engage in various ways in the production of meaning. Furthermore, if symbolic language made human abstract thought possible, we should not forget that it derives from the non-symbolic, both iconic and indexical communication, shared by all animals. Eduardo Kohn explores this in How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human—another must for anyone interested in restituting to reality its inherent complexity.

Finally, thought is not a privilege of humans. If life is autopoietic and sympoietic it is, precisely, because it is indissociable from thought. Wherever there is creativity there is thought. And what is life but creativity and variation?

(*) Since, according to Parmenides, what is is, what it is not is not, and they should never be confused.

(**) Holobionts are inter-species assemblages or alliances. Many relevant contemporary biologists find the notion of “individual” beings problematic at best. We are all holobionts, that is to say, alliances of multiple species living in togetherness, they underline. See further Scott Gilbert, “A Symbiotic View of Life: We Have Never Been Individuals.” In short, mainstream Darwinist biology is giving way today to a new scientific paradigm based on biological hypercomplexity.

Would you know an ‘anti-Aristotle’ of his times? What’s the theory, or why you think such philosophers go on shaping historical, philosophical thought for so many centuries and creating such influence even when sometimes it’s ‘nonsense’ and many people should be mad about arbitrary categories in which philosophers put themselves?

Sorry I know the article was about rocks and plants and sympoiesis… but I got angry at Aristotle 😂😂

Being angry at Aristotle is normal – how could one not be? He’s a key figure in the history of philosophy, as he puts together many ideas, with a rather systematic intent, and has important insights about a huge number of subjects… but his way of thinking often proves rigid despite all its apparent nuances. The so-called pre-Socratic philosophers, on the one hand, and Plato, on the other hand, are far more fascinating. But they’re not exactly anti-Aristotelian: first, because they predate Aristotle; secondly, because they do not aim at playing Aristotle’s game of classifying reality, their concerns are altogether different: the politics of language plus an ethics (Plato), the relation between identity and difference (Heraclitus), the difference between being and non-being (Parmenides), the dynamics of the world (Empedocles, Democritus & Leucippus), etc. After Aristotle, both Epicureans and Stoics engage in ways of thinking that rival with Aristotles’ in crucial aspects, including logics and physics, but after Justinian I turned Christianity’s back to philosophy (as you may guess the relation between the two, Christianity and philosophy, has always been highly problematic, since philosophy has to do with freedom, curiosity, and perfection) Western Europe became void of any thought on the composition of the physical world… other than the Biblical story of the world’s creation (if that can count as thought!). And then, suddenly, around the 12th-13th centuries, the works of several Islamic philosophers were received by the Western Christians, in a moment of social and intellectual transformation in Western Europe, because such works dealt with medicine, cosmology, etc. and could provide new ideas. And guess who was the key author thus received? Aristotle. Arabic translations of his works and Arabic commentaries were rendered into Latin and half of the Church became Aristotelian, and ever since Aristotle has been part of the curriculum of Western education (in combination with a Christianised Plato).