I

Nietzsche claims that the way in which we picture the world affirms or denies what we are ready to put in it, in short, that our representations rely on a pre-representational basis, inasmuch as we see what we see depending on how we are inclined to value it. In other words, he underscores the view that the material out of which our ideas are made is ultimately axiological (from the Greek ἄξιος, “worthy”).

Now, two values stand out at the core of Nietzsche’s project: life’s untamed avowal (which he identifies with what he calls the “Dionysian”) and, opposite to it, life’s dismissal (on behalf of the representations by means of which we attempt at secure the world for us, representations which he groups around what he calls the “Apollonian”). Yet, Nietzsche himself develops two likewise different, in fact contradictory, views on such opposition: sometimes he interprets those two contrary terms, the Apollonian and the Dionysian, to be mutually exclusive (= view no. 1), whereas other times he expressly supports any Apollonian representation that does not turn its back on life’s rawness, which amounts to reconciling the Apollonian and the Dionysian (= view no. 2).

None of these tendencies can be said to be prevalent throughout Nietzsche’s work: they interfere with one another thus drawing a notional zigzag. Nonetheless, by thinking with more or less accuracy depending on the occasion, but always passionately and often insightfully, on their nature of such notional puzzle, Nietzsche was the first to put forward a critical philosophy of modern Western culture – again, on an axiological basis.

In this sense, we are all Nietzscheans. Inevitably, for by now we have had enough of non-Dionysian or closed Apollonian spheres: the Christian one proved miserable first, then ruinous; and the modern one followed suit.

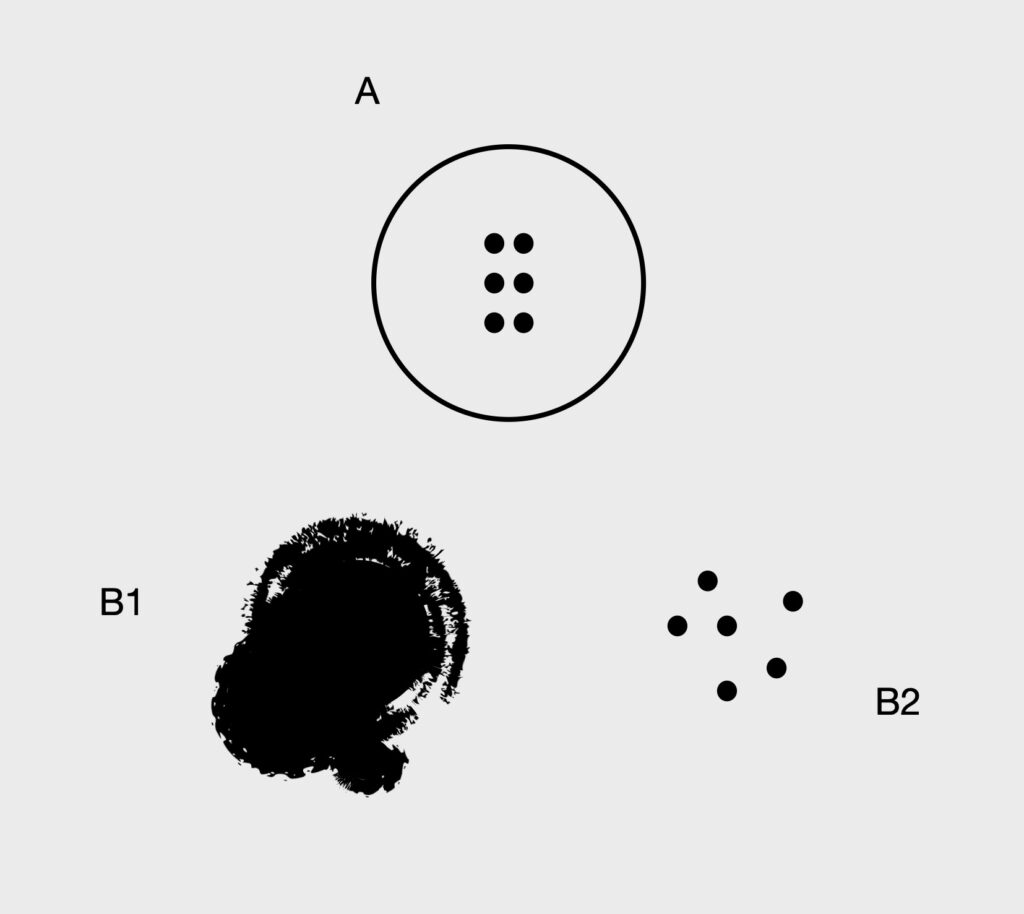

There is little mystery, then, in the fact that contemporary philosophy has been seduced by, and attempts to seduce us with, notions like the “fragmentary,” the “contingent,” the “indeterminate,” or the “negative.” I have summarized elsewhere the main options thus explored in contemporary theory with recourse to the this tripartite diagram, which I improvised during a seminary in Kyoto in March of this year; figure A depicts CLOSURE (i.e., the Apollonian, in Nietzsche’s terms), figures B1 and B2 OPENNESS (i.e., the reintroduction of the Dionysian, which Nietzsche famously portrays as an open sea):

Therefore, B1 and B2 must be seen as two different but similarly subtractive ways of contesting closure: by its complete dissolution which entails too that of the elements enclosed within it (B1), or by the random dispersion of these (B2).

I have equated B1 and B2 with “speculative realism” and “new materialism,” respectively. But a simpler way to put this would be to imagine how would you prefer to cross trough a dense forest: by knowing beforehand what you can expect to encounter in it (A), by closing your eyes and venturing yourself blindly into the unknown (B1), or by adopting an empiricist cum heuristic or pragmatic attitude (B2).

(Assuredly there is yet a fourth option similar to B2 but different from it in that it supplements pragmatics with a limited dose of Apollonian assurance which combines well with heuristics while it runs perpendicular to any empiricism, but I shall hopefully return to this in a future post.)

A, B1, B2. Note that so far we are still playing on Nietzsche’s chessboard, though – or rather Nietzsche’s X-board, to grant the game he wanted to play on it its novel features. What would happen then if, moving slightly aside from it, we were to ask: how did Dionysus and Apollo originally becomevalues – and for whom? Would their Nietzschean portrayal stand or would it not? And what implications should one draw from it?

We aimed at responding to these questions in our joint book Dionysus and Apollo after Nihilism (Brill, 2023), where, to cut the matter short, we identify Dionysus with the idea of a-yet-unwordled-earth-awaiting-to-be-wordled-or-at-least-not-reluctant-to-be-worlded, and Apollo with the idea of an-earthly-world-or-worlded-earth-reminscent-of-its-earthly-nature. The Dionysian and the Apollonian thus reconcile in our book (we follow in this Nietzsche’s view no. 2). Yet, at the same time, they remain in a permanent or dynamic disequilibrium that avoids totalizing them, for they are less the two halves of a single thing than each other’s multiplicative inverse – each other’s inverted image, that is. The expressions “permanent” and “dynamic disequilibrium” are Lévi-Strauss’s, who is one of the key references in our book, the other one being Heidegger, but careful here!, by this we mean neither the so-called “first,” nor the so-called “second” Heidegger, neither the Heidegger of Sein und Zeit, who focusses on the Da-sein’s throwness, nor the Heidegger that thematises human receptiveness towards an always-withdrawing “being,”neither the thinker of human exposure and vulnerability, nor the neo-Eckartian mystic, but what we call the “third” Heidegger, the Heidegger of the “Fourfold” (Geviert) formed by “earth,” “sky,” “mortals,” and “immortals,” which we reread (as I have further done later, as well) in Guattarian fashion (since Guattari, too, plays with a quadrant) as the overlapping of the “real,” the “posible,” the “given” and the “given.”

In a nutshell, then: the dynamic disequilibrium of Dionysus and Apollo as twin gods represents a non-subtractive way to escape CLOSURE, a way to rethink OPENNESS as neither dissolution nor dispersion.

Nevertheless, the dynamic disequilibrium of Dionysus and Apollo reflects an ever deeper dissymmetry. This idea can be read between the lines of our book, but lacks a proper statement there. Dealing with it now, however briefly, will help me to clarify what I take to be a truly important point and, additionally, to put my current work on Nietzsche and, above all, Guattari (but also on Heraclitus and Plato), in due perspective; and to reaffirm the central role that Dionysus and Apollo after Nihilism plays in what I am doing and will be doing over the next few years.

II

Althusser once wrote that “it is impossible to leave a closed space simply by taking up a position merely outside it, either in its exterior or its profundity: so long as this outside or profundity remain its outside or profundity, they still belong to that circle, to that closed space, as its ‘repetition’ in its other-than-itself.”[1] In the last instance this, too, is the problem with Nietzsche’s game – there where Nietzsche tends to merely substitute Dionysus for Apollo (see view no. 1 above), which is also how he has been commonly interpreted.

For all its restrictive claims, the post-Greek dismissal of Dionysus, which begins with Christianity attributing Dionysian traits to the “Devil” (literally: God’s antagonist), is an excess that has not only had, however, an eroding effect of its own, to wit, the curtailment of our freedom; it has had a corrosive after-effect as well: the renunciation of all responsibility.

For “House” and “Cosmos” (as Deleuze and Guattari put it in Qu’est-ce que la philosophie ?), “territory” and “deterritorialization” (Guattari’s nuclear categories), go hand in hand; as do “care” (read: “responsibility”) and “freedom,” to employ Sofya’s preferred terms, or, again, “world” and “earth,” Apollo and Dionysus. We do know that the capacity to deterritorialize and be deterritorialized, to exceed the limits of any conceivable territory (physical or not), is typically human. Our physical maladaptation – “we are a turtle when we take shelter under a roof, a crab when we take up a pair of pliers, a horse when we trot through the countryside,” says André Leroi-Gourhan[2] – makes us deterritorialized and deterritorializing creatures. A poem or a painting is the effect of deterritorializing powers, as is, for example, adding red curry to a stew or looking at a map of Southeast Asia and deciding to move to Laos. Moreover, it is undeniable that humanity’s deterritorializing powers have increased exponentially, both quantitatively and qualitatively, in recent decades. In other words, there is nothing natural about us except the unnaturalness that defines us. This is why conservative reterritorializations, whether political or religious, and whatever their sign, are extremely dangerous. Because even if we accept that, in almost everything, there are some small (or not so small) natural details that are difficult to ignore (the night, for example, is naturally different from the day), the fact is that the added or purely deterritorializing value that we can attribute to them is much greater (after all, I can decide whether I spend the night sleeping or listening to one of Bach’s latest fugues). But there is also the care of things. Caring for things, even things that in principle do not concern us (a plant, a pet, another person) is also something specifically human. In other words, we do not just exercise our freedom: we freely impose responsibilities on ourselves. And it is here that another capacity emerges that characterizes us as much as our capacity to deterritorialize and to be deterritorialized: our capacity to contain, that is, to territorialize or reterritorialize that which, if not, would disperse and become extinct, or become indifferent. This double concern can then be expressed by the formula: from the House to the Cosmos, and back again.

Despite being an extremely powerful deterritorializing machine (“there is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus”), Christianity laid a fatal curse on any further powers of deterritorialization – while it dissolved one by one all the ancient territorialities, that is. Initially, modernity limited itself to replicate that gesture in what might be labelled as a system update (“there is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; you are all equally destined to achieve Human progress”). First, then, a moral God built a prison and placed us inside it, warding off anything that could excite our natural quest for freedom. Later, we killed that God (a purely human creation, after all, yet an allegedly omnipotent God) and occupied his vacant throne. From this moment onwards, we told ourselves, reality would be whatever we fancy. Initially, in the image of that moral God, we chose to assign to it a closed, predetermined meaning: that of an unilinear, progressive tale, the mainstream modern narrative. Next, we have declared it a (postmodern) playground for no matter what, asking ourselves whether the death of God does not resemble an unconditional “yes,” whether it does not open onto the “Great Outdoors” (Meillassoux) of a “crowned anarchy” (Deleuze).

The latter was Nietzsche’s temptation (see once more view no. 1 above), for Nietzsche aimed at erasing God’s name and (re)writing over it that of Dionysus, on whose mirror our own reflection should then appear free of any chains: Dionysus against the Crucified. But then, the willingness to renounce to any House so as not to fall back on God’s prison, to be wonder-less wanderers in a permanent exile (as Badiou likes to say),[3] must be seen as the “repetition in its other-than-itself” of the decision to confine reality within the walls of that prison: Dionysus against the Crucified who, by having to save us, makes patent our prisoner condition, from which paradoxically – here is the key point – Dionysus, too, purportedly delivers us. There is no better way to reinforce something’s presence than by telling ourselves we are no longer there.

Today, the path we have thus taken to escape the inescapable – which we would only be in position to overcome if we were to redraw the board https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/opphil-2022-0209/html on which we have been playing a single game for more than two thousand years – bifurcates in three distinct directions: either reality proves meaninglessness in the lack of anything capable of bringing it together (our will being impotent thereof), or else we engage in a permanent trial and error without setting any durable horizon for it (as though situatedness ought to entail unreflectiveness), or, else the vertigo induced on us by the absence of any rules (which is fine, but perhaps only to start with?) makes us want to try no matter what and no matter how (consumerism being the corollary). Leaving this third path aside – for it has no philosophical relevance whatsoever – the other two form the Janus of contemporary theory with its somber and festive profiles, nihilist and pragmatist, childish and senile. But they run down that same slippery slope.

III

We definitely need a new game, and it is here that rethinking how did Dionysus and Apollo becomevalues makes the difference.

For even if pragmatism is preferable to nihilism (who doubts it?), it is not enough. Nor are we, and this may well be the whole issue. We are persuaded we are just because, first, we removed any consistency from reality and transferred it to an extra-cosmic God; and once we have killed him (at last), we feel orphans of reality. But reality is there, and it interpellates us and rocks us. Even a constructivist like Guattari ends up talking about phenomenology, which need not remain anchored to its Husserlian premises! In short, Dionysus and Apollo are not simply values: they name, like any other gods and goddesses (i.e., they are names we give to), forces that are immortal (or, in Nietzschean terms, eternally recurring), forces that make and unmake us like they make and unmake everything else, for they traverse all things. Dionysus names the power of deteritorialization, Apollo the power of reterritorialization, and togetherthey form and transform reality, which is broader than ourselves.

This and no other was the teaching of Greek tragedy, as it was the purpose of the Greek pantheon.

In a memorable passage of Sophocles’s homonymous play (ll. 450–7), Antigone tells Creon that it is neither Zeus who makes her (note the dative μοι on l. 450) defend the burial of Polynices’s corpse, nor the justice due to the gods of the underworld or to humankind’s laws, but “an unwritten, unshakable, and divine usage […] which nobody knows whence it springs forth” (ll. 454–5, 457). Which can its root be then, if it predates both gods and men, or, more precisely, the ways in which they relate? In the Greek worldview, before gods and men there is only the earth (Hesiod, Theog., vv. 116ff.), who is mother to them both (Pindar, Nem. 6, vv. 1–2). Yet, the fact that Antigone mentions a “usage” (μόμιμος), makes it patent that there is something specifically human about it. If it is a “custom,” it cannot be but human: a human usage that precedes in time any ritual relation between men and gods and any form of divine inspiration. Again, what can this be? Response: the making of the difference men|gods, that is to say, their distribution qua terms of a dual structure in which A proves to be what it is inasmuch as it differs from B, and vice versa, their co-implied difference thus being the meaningful relation that determines at once their individual and joint being.

Dionysus, Apollo… and all other gods and goddesses as well. “Immortal mortals, mortal immortals, leaving each other’s death, dying each other’s life,” says Heraclitus (frag. DK B62). The double chiasmus implies that not only do the gods live lives which are deeper and wider and longer than men’s lives, but that they need of the lives of men (like they need of the lives of everything else) to take form, for their overflowing powers must be delimited and contained to become expressive in concreto; and vice versa, that human lives are exceeded and sustained by these, from which they get their shape and to which which they give shape hic et nunc.

A new figure, different from A, B1, and B2, is formed here. Something like this:

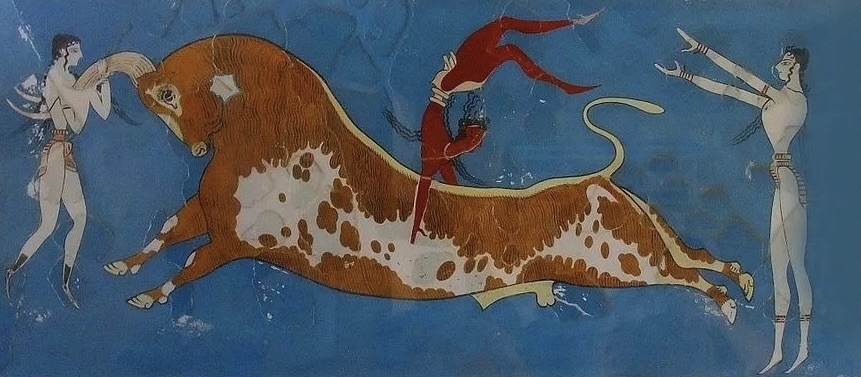

which, interestingly enough, remains for us, Europeans, a typically Greek one (in German it is called ypsilon, which is its original Greek name; in French, i grec (“Greek i”); in Spanish, i griega). Its shape is reminiscent of the horns on which Minoan athletes jumped during their most important religious festival.

Fresco from the Great Palace at Knosos, Crete. (Public domain)

The Greek “Y” symbolizes (or rather, graphically represents; Pierce would have said that it is an “icon” rather than a “symbol” of) life’s knots or dual structures – that is, its enigmas. Let us think, for example, of the crossroads where Oedipus meets Laius, which – Sophocles is careful to specify – is not in the shape of an “X” but of a “Y”; in the fact that in the Iliad Hector confronts Patroclus thinking he is Achilles, and that Achilles in turn must confront himself when he confronts Hector, for the armour of Patroclus that Hector wears is in fact his own; in the Entrückung or “snatching away” (as Hölderlin calls it) of Antigone, which enables her to cross between worlds; in the reciprocal but unequal relationship that unites and separates the Erinyes and the Eumenides in Aeschylus’s Oresteia; in the logic underlying the fragments of Heraclitus, which Clémence Ramnoux (followed by Blanchot) once described as “the most difficult thing to think about,” and which echoes the very structure of the riddles of Apollo, the god of the bow and the lyre; in the way Parmenides thinks the joint articulation of “being” and “non-being,” according to which what seems less is actually more; in the strangely symmetrical qualities of the two most complex and longitudinally distant but, at the same time, closest of all Platonic concepts, namely, those of τὸ ἀγαθόν and χώρα; or in Aristotle’s two causal axes: material and formal, final and efficient. The same applies to Dionysus and Apollo, who shared one sanctuary: Delphi, where Dionysus was worshiped in the winter and Apollo in the spring.

Only that “Y” (which is not only Greek but also indigenous Amazonian, Papuan…) can bring us back to the realm of possibilites we one day chose to close, and that we have anything but regained by attempting to escape that closure while maintaining its premises; and only that “Y” can help us to move forward from there. Variant: only that “Y” will truly allow us to supplement (in the Derridean sense of the term)the “thought,” and hence to expand the sphere of the “thinkable” beyond it (i.e., beyond A, B1, and B2), because only that “Y” can raise in us the awareness of what lies “unthought” beneath the “thought” and as the non-beforehand-predetermined horizon of the “thinkable” – unless we indulge ourselves by repeating the same empty formulas over and over again (immanence, otherness, becoming, etc.)

IV

Our book, Dionysus and Apollo after Nihilism, sets the stage for, and prefigures, this gesture. Afterwards, I have prolonged this same line of thinking in several publications, including three forthcoming books. On the one hand, I have argued that Nietzsche himself leaves room for something beyond his Dionysian philosophy, that there is moreover, as scandalous as this might sound, an Apollonian Nietzsche that predates Die Geburt der Tragödie and Die dionysische Weltanschauung and that expands, if intermittently, until Zarathustra’s fourth part, where it clearly its zenith. My upcoming book with Peter Lang: Nietzsche’s Pre-Dionysian Apollo and the Limits of Contemporary Thought,moves along those lines. Yet, on the other hand, I have tried to show that one of the most suggestive philosophical voices today revered, less problematic than Heidegger’s due to Heidegger’s commitment to Nazism, to wit, Guattari’s, points in a direction which is not that of subtraction, if his philosophy is read independently from Deleuze’s. In fact, Guattari puts forward an extraordinarily complex chiastic thought which defies the modern and post-modern conceptual imagination. I make this claim in my upcoming book with Palgrave Macmillan: Guattari Beyond Deleuze: Ontology and Modal Philosophy in Guattari’s Major Writings, to be published on December 2 of this very year. Furthermore, I intend to inquire into the early development of such chiastic thought, which Guattari partly adapted from Leibniz and which I have examined elsewhere in relation to Fichte, through a comparative study of Heraclitus and Plato; and my purpose is to put together the results of such inquiry in yet another book with Peter Lang which is provisionally titled: Ulyses’s Mast: Prolegomena to a Post-nihilist Philosophy.[4]

Meanwhile, Sofya has undertaken the task of exploring the bodily and imaginary ways in which our being-there in the midst of reality and lacking any a priori guarantees, intersects with our being-with not only other humans (and their ghosts), but also other species (and their own ghosts); and not only other material species but other incorporeal species, as well. Life’s greater ghosts or transcendental qualities, which are the condition of possibility of whatever succeeds to vectorize itself (thus becoming present) and of its receding into non-being for other things to become present in turn. Back to the gods and to our lives fully traversed by them, of which butō (philosophy’s obverse) is but the dance…

Only out of them – only out of those greater ghosts – will we be able to project freely, travel through, and dwell in, as many worlds as we may like to, for everything else will rapidly crumble and fall to powder. Those worlds will too, of course. But when they do, they will do so leaving a gleam behind.

Notes

[1] Louis Althusser and Étienne Balibar, Reading Capital (London: New Left Books, 1970), p. 53.

[2] André Leroi-Gourhan, Gesture and Speech, trans. Anna Bostock Berger (Cambridge [MA] and London: The Mit Press, 1993), p. 246.

[3] Alain Badiou, Théorie du sujet (Paris: Seuil, 1982), p. 185.

[4] For other publications of mine dealing with these and other related issues, see the “External Publications” section.