Detail of a 1st-century Roman copy of one of the statues of Athena sculpted by Myron and housed in the Parthenon. Madrid, Prado Museum. Photograph taken by the author

I

“I will not turn you into stones with snake-haired terror (schlangenhaarigem Schrecken): with my shield of beauty (Schild ,Schönheit‘) I protect myself.” Thus reads one of Nietzsche’s unpublished fragments (no. 9[17]), from 1883.

Who – or what – does Nietzsche write against? It is unclear. Yet, it can be surmised he directs these lines against Lou Salomé and Paul Rée, with whom he had broken towards the end of 1882. Be that as it may, there is good reason to suppose that the shield in question is no other than Athena’s, given the oblique but unequivocal reference to Medusa’s snake-haired gaze, for it is the Gorgon’s head that Athena carries on her shield as a sign of Medusa’s beheading by Perseus, which Athena herself had incited.

“Ceto bore to Phorcys […] | […] the Graeae | […] and the Gorgons, who live beyond eminent Oceanus | at the [world’s] limit, towards the night,” says Hesiod (Hes. Th., vv. 270–5). Medusa and her dreadful sisters stand, thus, at a threshold: the threshold that divides Zeus’s cosmological domain (or the world, as we know it) from Nyx’s, and hence Chaos’s, offspring. Much later, in Ovid’s retelling of Medusa’s myth, her transformation from a mortal and beautiful woman into a monster due to Athena’s curse, is connected to Poseidon’s sexual attack on her in Athena’s temple (Ovid, Met., IV, 794–803), that is to say, it is implied by Poseidon’s profanation of the latter.

Nevertheless, it would be wrong to assume that Athena takes revenge on Medusa instead of Poseidon because she has no power over a fellow god. Whatever their tales (which are precisely that: tales), it makes no sense to distribute guilts among the Greek gods, for they name forces, not persons. As the earth’s immortal, everliving forces, the gods confront one another and, as a result, see how their own areas of influence are at times broadened and at times narrowed by their ongoing disputes. Plus, their dynamic exchange affects the lives of mortals, whom they sustain (cf. Heraclitus, frag. DK B62). If a mortal has sexual intercourse (which is what Poseidon’s presence means, for he is the god of the depths) inside Athena’s temple, where a clear vision of things must prevail instead (notice that Athena is the goddess of the clear gaze), the consequence cannot be other than the confusion embodied by Medusa’s monstruous transformation; a confusion that, seen from a Greek perspective, cannot be identified with anything desirable – which is why it is severed or set aside.

(I have an extra-modern friend who reacts with perplexity when I tell him about the contemporary flirt with the idea of equivocality; when you are chased by a jaguar, he observes, you better know where to step next.[*] With this I do not mean to say that everything needs to be clear to us, let alone beforehand. Things often take time to become more or less clear, and some never do; plus, certain things are essentially ambivalent, and it is good that it is so. What I am questioning here is the preference for confusion, as such.)

Consequently, it makes no sense to read Athena’s curse of Medusa, which aims at drawing a line of demarcation between what is clearly and distinctly perceptible and what proves confusing, as the self-complacent violence exerted upon the Other, the marginal, the unspeakable, the fallen, by those who like the taste of victory. Reading it thus – as it has been recently proposed against the backdrop of the 70th International Festival of Classical Theatre of Merida – is not only an anachronism, but also the sign of a shameful misinterpretation of what is at stake in the myth. In other words, Medusa is not someone to be pitied, but the very epitome of confusion and danger at once.

Medusa, after a drawing on a Greek vase painting currently at the Louvre

II

These brief notes may help us to better understand, moreover, the well-known Ancient-Greek thesis that evil is irrational and that, therefore, the wicked act out of ignorance.

It is often interpreted that this is equivalent to affirming that the wicked act without knowledge in the sense that they ignore what they do. Once more, though, this amounts to interpreting the Greek thought-world according to non-Greek categories.

Evil is per se irrational, it eludes both thought and knowledge. Therefore, the wicked act out of ignorance. This is the thesis. Now, irrational in Ancient Greece is, by definition, that which escapes the measure of any εἶδος or “idea,” a term that denotes not su much the mental representation of something as the limit (read: the determination) which allows that something to appear according to its perceptible qualities (the brightness of the day, the darkness of the night, etc.). For the word εἶδος, in Ancient Greek, originally denoted something’s “visible aspect” and “form” – that is to say, the characteristic way in which something appears.

Thought, says Heraclitus (frag. DK B1), is witness to that appearing, and only through it can one expect to gain knowledge. Heraclitus employs here the term λόγος, which is commonly translated as “reason.” Thought is what allows us to distinguish all things. It is then, one may deduce, the opposite to Medusa’s confusion.

Why, then, can it be claimed that the wicked transgress such λόγος with their doings? To respond to this question, it will suffice to ask how pleasure happens to appear to our understanding. It does so in expansive terms whatever its form. Indeed, pleasure wants to spread and thus to last.

Now, where is it that the wicked find pleasure? They find it in contorting everything. Their idea of pleasure is thus contrary to the very εἶδος of the latter. In short, the wicked confuse (read: mix) pleasure and pain, which is why they transform the others’ pain into their own pleasure. But this means that they do not let things appear clearly before them – and before us.

(Again, I do not mean to say that everything must be clear to us, let alone that it ought to be clear a priori. Things take time to become clear, if they do; and it is fine if some things prove ambiguous. What I am questioning here is their distortion.)

The wicked thus act under the sign of Medusa, whose snake-like hair symbolizes confusion. (Notice that it is Medusa’s head that is snake-like.) Conversely Athena, the goddess with clear eyes, symbolizes the clear vision of things and thereby thought, which is why she carries imprisoned on her shield Medusa’s head.

III

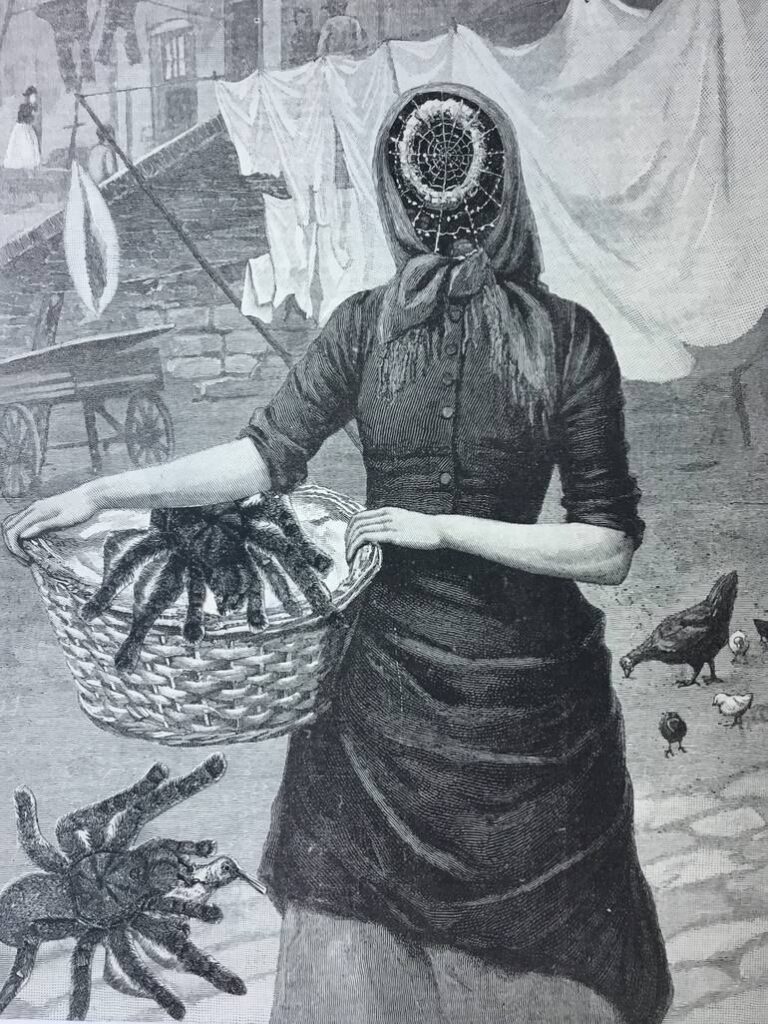

The room where I am writing this note is packed with boxes of books, for we are about to leave for Berlin after the two years we spent in Madrid on our forced return from St. Petersburg. On the floor, books are like grain that chickens peck at. Yet the fact that they will remain closed in their boxes for two or three months highlights the fact that they are in transit between two worlds, one gone, another one yet to come. I look back over the last year and remember someone who, strangely, reappeared in it after a good many years of silence with an apparently fragile appearance. But after several months of pretended kindness – impossible not to think here of Max Ernst’s Une semaine de bonté, between whose pages parade a plethora of Victorian characters who are never what they seem to be – the little bird revealed itself a poisonous spider that enjoyed trapping reality in its icky web and changing being into non-being in order to feel sorry for its own inherited fake misfortune – as false as the pseudo-reality in which all of Wilde’s secretless sphinxes live immersed…

Max Ernst, illustration for Une semaine de bonté (1934)

I reread Nietzsche’s unpublished fragment and I smile. Plus, I recall that, in the Odyssey, it is Athena who accompanies Odysseus and helps him to tell what is from what is not. Furthermore, it can be said that Ancient-Greek philosophy took up the problem of the rivalry between presence and absence as outlined in the Iliad as much as that of the rivalry between reality and its ψεύδη or “falses appearances” outlined in the Odyssey. It is ultimately the same problem; but a problem that only makes sense at the price of Medusa’s head served on a platter – or, at the very least, there where her stifling kingdom crumbles like sand.

c.

[*] Athena’s rejection of Medusa is also an indigenous feature: like her, the Yanomami fear that which makes their heads spin (Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman [Cambridge, Mass., and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013], 40) and the Atchei fear distortion (Pierre Clastres, Chronicle of the Guayaki Indians [New York: Zone Books, 1998], 219–20).