December 9, 1973. In an article published in the Corriere della Sera Pasolini laments the acculturation brought about by capitalism. In particular, he deplores the loss of the “peripheral cultures which, until a few years ago had their own life assured – essentially a free life, even if within the poorest, or even miserable, peripheral areas” of the modern Italian cities.

“Fascism,” Pasolini goes on to say, “did not achieve what consumerism has in terms of centralism. For Fascism proposed a social model that was both reactionary and monumental, but which, ultimately, remained a dead letter. As a consequence, several non-bourgeois cultures (peasant, sub-proletarian, and proletarian) lived up to their old models; in fact, Fascism only aimed at obtaining their nominal adhesion. Conversely, the adhesion to the model imposed today by the Centre is total and unconditional. No other cultural models are left alive. It is all finished in this sense. It can be even argued that the ‘tolerance’ characteristic of capitalism’s hedonistic ideology is the worst form of repression known in human history. How does it operate? In two revolutionary ways: through the transformation of the infrastructures and through new circuits of information. General motorisation and new roads have tightly linked the periphery to the Centre by abolishing all material distances. But the revolution in terms of information has been even more radical and decisive. Through the television, the Centre has assimilated the whole country, which was so very diverse and rich culturally. A new era has commenced – but one characterised by the erasure of all differences and the destructive homologation of any authenticity. […] And the Italians have accepted with enthusiasm this new model imposed by the television on behalf of the welfare state, or, more exactly, to save everyone from poverty.”(⊕)

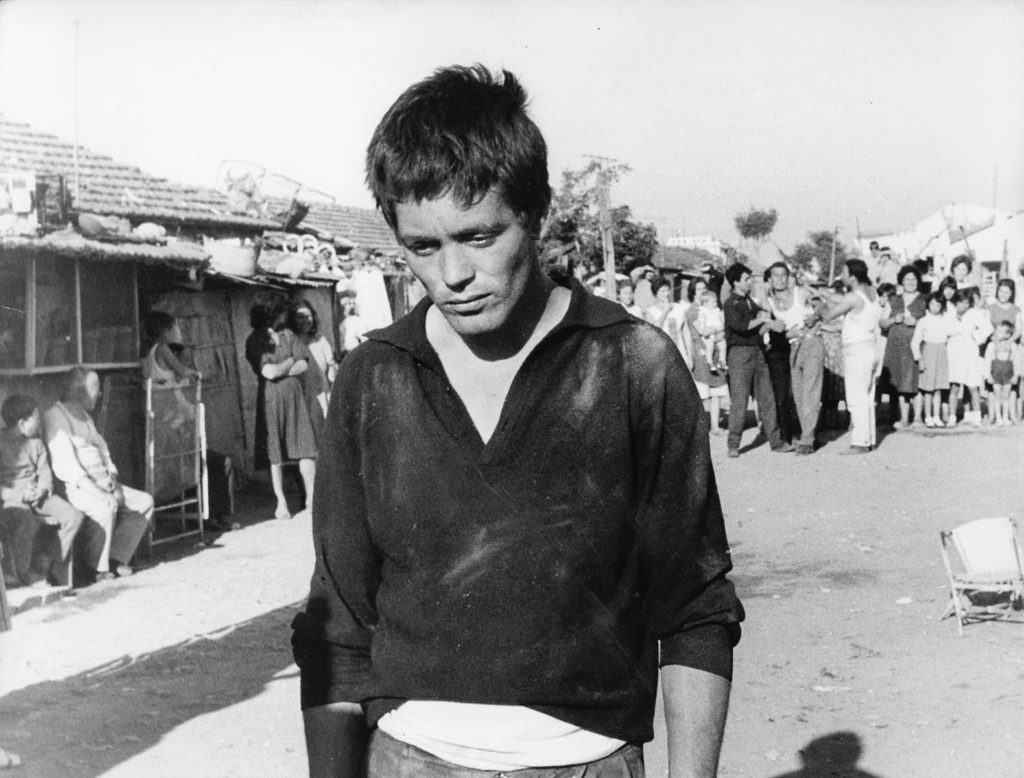

Similarly, in another article published in the same journal on October 8, 1975 – i.e. less than a month before his brutal murder – Pasolini confesses that, if he were asked to reshoot Accattone (his first film, from 1961), he would be unable to because he would no longer find the people he had recruited as actors: not only their culture and mentality, but also their physical types, are extinct. For they belonged in a sub-proletariat and a proletariat which are no longer. Their characters have been erased from the face of the earth, avers Pasolini.(⊗)

As we have written elsewhere, Pasolini goes as far as to speak of an “anthropological mutation” or “revolution” by which the petty bourgeoisie, with its American-shaped combination of pragmatism, superficiality, hedonism, and self-indulgence has become de facto the model for all humanity. We have already examined the effects of such “revolution” upon the fundamental affective aspects of being on which human lives rely however differently they may be experienced. So we should like to briefly examine here, in turn, the cultures that it has suppressed; that is to say, its acculturation effect, which Pasolini does not hesitate to label as a “cultural genocide.”

Peasants, Sub-Proletarians, and Proletarians

The urban revolution of the 1950s and the two subsequent decades entailed massive flows of population from rural to suburban areas in Italy and, more broadly, Europe. Despite the governmental propaganda, work opportunities were few in comparison to the large amount of migrants who felt encouraged to migrate, and the promised improvement in the living conditions of peoples who, only one decade earlier, had experienced war and, as a result, misery, proved to be nothing short of a sham: it was a deceiving strategy aimed at motivating rural migration for the purpose of industrial development, capital growth, and the consequent enrichment of the ruling classes. Besides, not all rural migrants were willing to assume the drastic changes in habits and mentality that settling in the suburbs demanded from them, that is, not many were ready to embrace individualism as a newly-imposed ideology which questioned their traditional social values and to subject themselves to abstract laws and a working ethics which they rightly suspected were but means to grant compliance-based exploitation; nor were they happy to lose the freedom of movement of their pre-urban lives. Hence many did not adapt to the new setting: some of them refused to whereas others tried but could not. A new sub-proletariat – not very different from that of the mid-19th to early-20th century, and which is admirably depicted in Accattone – consisting of pimps, thieves, prostitutes, etc. was thus born; and, with it, new social conflicts among its integrants (rivalry, delation, etc.) and between these and the other social classes: the bourgeoisie, which viewed the sub-proletarians as a menace and judged them as per their “free” individual adherence or refusal to comply with a state of things that, to the eyes of the bourgeoisie was all the more “natural” inasmuch as it represented “human progress”; the subsisting peasantry, which generally felt inclined to support its children, but other times perceived them as deviants and thus opposed them as dangerous strangers; and the proletarians who had adapted to urban life at the price of many renouncements which the sub-proletarians found deplorable – just like the proletarians deemed despicable the intractability of the sub-proletarians. Thus, for example, Accattone’s rejection by his proletarian wife and her family in Accattone, or the contrast in Mamma Roma (1962) between an ex-prostitute’s hopes that her peasant son becomes a proletarian, the son’s homesickness, his sub-proletarian present, and his detention and imprisonment.

Yet initially peasants, sub-proletarians, and proletarians, observes Pasolini, shared, unlike the bourgeoisie, and especially the consumerist-oriented petty-bourgeoisie, “absolute [moral] values”(⊛), e.g. pride and faithfulness to their own kin; values which, depending on the circumstances, could become their opposite, i.e. moral defects like, say, prepotence and injustice; but such defects which, stresses Pasolini, were/are “human defects,” hence too “personable,” and “socially justifiable,” because they are “the defects of men who obey a scale of values different from that of the bourgeoisie”(⦿) – a scale of values in which, by the way, “purity” is still meaningful in the end, which is, above all, what Pasolini films in Accattone, as its incipit – four verses from Dante’s Divine Comedy – anticipates: “an angel took me, and the one in hell / shouted at him” ‘Hey, you, the one in heaven, why do you wish / to take him from me and to draw him with you to eternity?, / why does a single little tear of his make me lose him?” (“Purgatory,” Song V, vv. 104-107; Pasolini’s own emphasis to stress how beautiful and relevant an apparently-minor thing can be, here “a single little tear,” when it testifies to an inner transformation). Compare this to Rossellini’s and De Sica’s Neorealism, which, despite its cinematographic greatness, limits itself to pity the oppressed in humanist terms; or to the early-Fellini’s and to Antonioni’s otherwise lucid portrayals of bourgeoise ennui.

Extra-Moderns and the Savant Classes

As for the extra-moderns of what was called, in the 1970s, the “Third World,” Pasolini said unambiguously to Michel Maingois: “In my films, barbarism is always symbolic: it represents the ideal moment of mankind.”(⊚) For, as we have seen (here), they were, on Pasolini’s reading – which we do share – far more sensitive than the modern industrialised classes to the gleaming of the “sacred” that frames, consciously or unconsciously, the nucleus of any truly-human experience.

The same can be applied to the proletarians, sub-proletarians, and peasants mentioned in the preceding section. On the other hand, before being transformed into the “ghosts,” i.e. into the replicants, of the petty bourgeoisie,(⊙) these were neither ashamed of their “ignorance” nor did they show – unlike the petty bourgeoisie – disrespect for what can be authentically labelled “culture,” underlines Pasolini.(⦷) In other words they knew they belonged in “life” and felt in contact with the “mystery” of “reality”(⊜) – the very mystery which nurtures art, literature, and thought.(⦶). Thus Pasolini’s adaptations of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Chaucer, and Boccaccio.

In this, moreover, the extra-moderns, the European non-bourgeois classes, and some members of the Western savant classes (some artists, intellectuals, and, exceptionally too, some small traditional sectors of the aristocracy and the high bourgeoisie truly committed to artistic patronage) are to be seen as enemies of the petty bourgeoisie as long as they are more interested in living and thinking life than in consuming goods – hence, too, as potential allies in the struggle against capitalist acculturation.

The “Revolutionary Force of the Past”

Italo Calvino reproached Pasolini what he saw as a dangerous nostalgia of what is called in Italian the “Italietta,” i.e. the provincial, proto-Fascist Italy prior to its modernisation. Pasolini responded elegantly: if Calvino is to say so it cannot but mean, he complains, that he has neither read a single verse of my poetry nor a single line of my novels, he has not watched a single sequence of any of my films, and thus, apparently, he knows nothing about me. Furthermore, adds Pasolini, he obviates I have been bitterly persecuted for two decades by the authorities of that “Italietta” he accuses me of being nostalgic of; and if the youth may well not know it, Calvino should. I am nostalgic of something else, argues Pasolini: not so much of a supposed “golden age,” as the influent communist leader Maurizio Ferrara reproached him in turn, but a reality which was both less superficial and less homogenous. “The men of that former universe,” writes Pasolini, “were consumers of strictly-necessary goods, and it was this fact that rendered their lives necessary, regardless of how poor and precarious such lives were; whereas it is clear that living out of superfluous goods turns life equally superfluous.” (⊖) This as regards the superficiality of modern life. As for its homogenisation, Pasolini writes: “the cultural model offered to the Italians today (and to all men everywhere for that matter) is only one. And it is our lives, our very existences, that are forced to conform to it: our behaviour and our body. It is in these domains that the values, not yet fully patent, of a new one merely-consumerist society are experienced, and with them the most repressive totalitarianism ever seen.” And he gives a most telling example: “not a single guy of the borgate [= the Roman suburbs] would be able to understand today,” he says, “the slang still reflected in my own earlier novels. What an irony! In order to understand it he would need to consult a glossary, like a typical bourgeois from the North!” (⊘)

Hence Pasolini’s thought-provoking words, with which he put an end to his 1971 documentary on the ancient city of Sana’a in Yemen, titled The Walls of Sana’a, asking the UNESCO to protect these and the city within them on behalf of the “revolutionary force of the past.”

We would like to begin a new year with this reflection – and, more importantly, with these words of Pasolini.

(⊕) Pier Paolo Pasolini, Scritti corsari (4th ed.; Milan: Garzanti, 2008), pp. 22-23 (hereinafter our translation).

(⊗) Pier Paolo Pasolini, Lutheran Letters (New York: Carcanet Press, 1987), pp. 100-105.

(⊛) Ibid., p. 101.

(⦿) Ibid., p. 102.

(⊚) Michel Maingois, “Interview with Pier Paolo Pasolini,” Zoom (October 1974), p. 24.

(⊙) Pasolini, Lutheran Letters, p. 102.

(⦷) Pasolini, Scritti corsari, pp. 23-24.

(⊜) Ibid.

(⦶) Compare, for example, Pasolini’s ongoing reflection on the human condition – in his novels, poems, films, and essays – and the spontaneous, ad hoc insights on it voiced, for instance, by Accattone’ protagonists.

(⊖) Pasolini, Scritti corsari, p. 53.

(⊘) Ibid., p. 54.

(⦹) These words are often interpreted as an index of Pasolini’s many “contradictions”: he was incomparably “lucid,” we are told, but also “unrealistic;” admirably “bold” but so much that some of his views (e.g. on sexual freedom) can be deemed “improper”; a “progressive” mind, yet one possessed by too “romantic” a spirit, etc. Those who read Pasolini in this way, we should like to argue, have simple not understood a single idea of his. In fact, by accusing Pasolini of displaying here and there a “contradictory” thought they only prove adamant to think beyond the prejudices Pasolini himself denounced.

Franco Citti in Accattone (1961)