A diagram is not merely a way to illustrate something. It is rather the transformation of “content” into “form.” It therefore involves a recoding, e.g., the recoding of an idea in visual terms.

The following diagrams attempt at diagramming Antigone’s rhythm, in particular the confrontation between Antigone and Creon and that between Tiresias and Creon, as well as the conceptual premise and outcome of Sophocles’s play, whose deep meaning (which intuited through his notions of Entrückung and Verrückung) we seem to have lost by identifying it with an ode to political freedom and projecting onto it our own modern concerns.

Additionally, AntiGONE glimpses into the essence of Greek tragedy, following Nietzsche(*) but offering an altogether different interpretation of what is at stake in it – which has neither to do with destiny’s overwhelming power over and against our fragile human lives, nor with the suffering that these undergo accordingly.(**) The diagrams hint at it, as well.

Below are the diagrams, then – six in total.

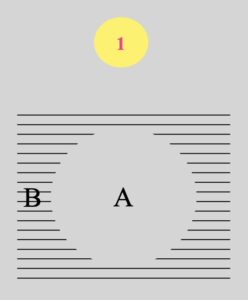

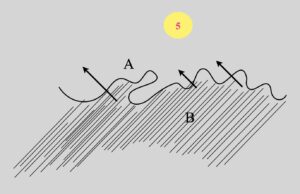

1. Creon has forgotten the essential: the sacred background on which mortal life rests; that is, he has forgotten what makes men mortals and gods immortals, he has expelled world B to the outskirts of world A:

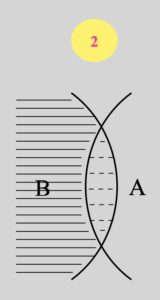

2. Ideally, both worlds should be kept in equilibrium, and humans should take care of their intersection:

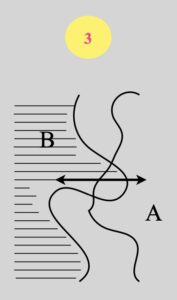

3. Yet, this balance is always lost, because humans irremediably lose sight of the essential and refuse from it; hence the relationship between the two dimensions (world A and world B) is always-already unstable:

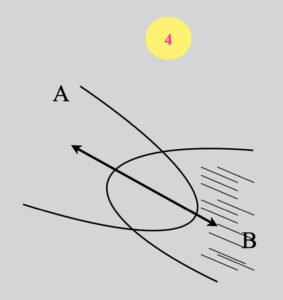

4. Antigone and Creon (and likewise Tiresias and Creon) confront each other, and through their confrontation we witness the confrontation of both worlds (the diagonal nature of the diagram seeks in this case to express the violence of this confrontation, i.e., its dynamic character):

5. Finally, the ground (the forgotten, the repressed) breaks through and rises to the surface:

6. It does so, though, in such a way that it floods and sweeps through the world A, engulfing it as a tsunami swallows the earth. The tragedy thus reaches its climax, moving the audience at once to horror, pity, and understanding:

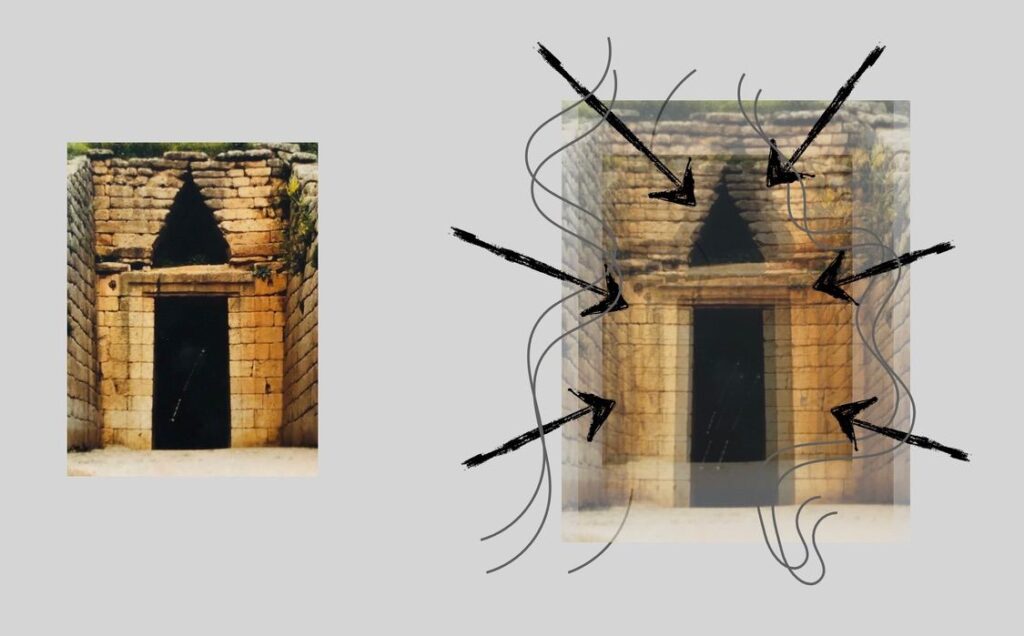

This one, on the other hand, is a supplementary diagram (inspired by the entrance to the tomb of the Atridae in Mycenae) of attraction towards world B, and of entry into it.

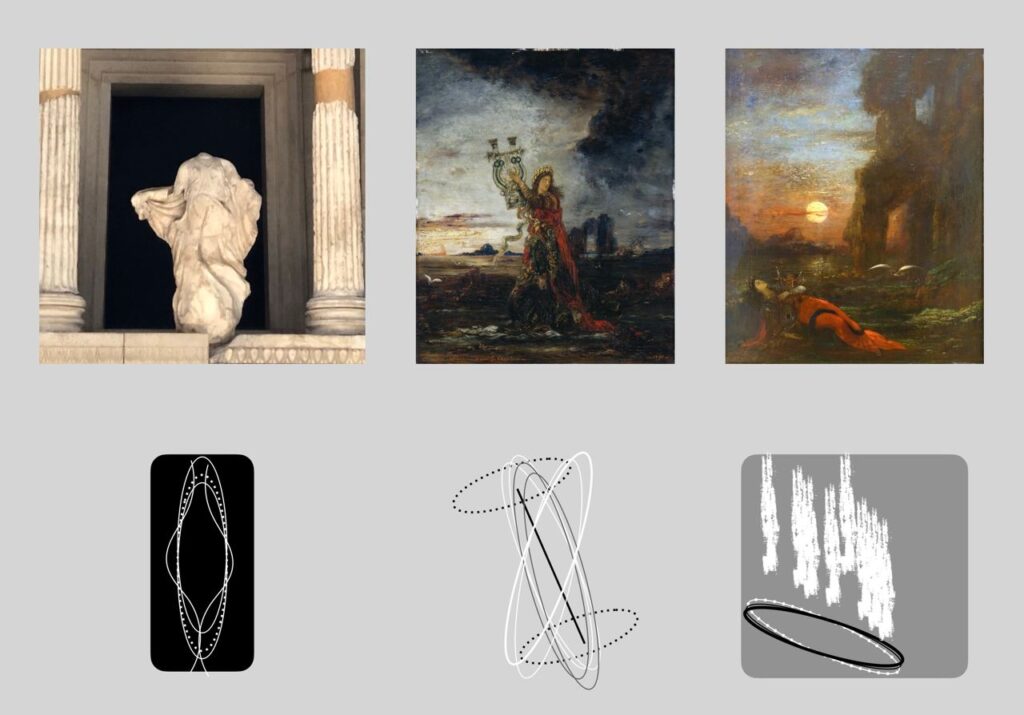

And finally, these are three supplementary diagrams centred on the figure of Antigone and the three phases through which her activity may be said to pass (intuition, proclamation and death), based on the Nereid Monument from Xanthos and two paintings (Arion and The Death of Sapho) by Gustave Moreau, respectively.

———

(*) On whose oft-overlooked pre-Dionysian Apollo Carlos will be soon publishing a monograph Peter Lang, titled Nietzsche’s Pre-Dionysian Apollo and the Limits of Contemporary Thought and that re-assess inter alia Nietzsche’s take on the birth of Greek tragedy, the “Aorgic” (Hölderlin), and the “Archaic” (Creuzer).

(**) It is, conversely, around the idea of the inevitability and pervasiveness of human suffering that Nietzsche’s interpretation of ancient tragedy – which is based on a misreading of Oedipus Rex through Hamlet‘s lens – gravitates.