For Mahoro Murasawa and Kevin Swierkosz-Lenart

I

Like everything else, music is (to use a Guattarian concept) an “optional matter”; that is to say, there are many ways to organize any sound material.

Take, for instance, the chromatic scale, which represents a way of classifying and gathering together a finite number of sounds, namely, twelve so-called notes which correspond to seven tones (C, D, E, F, G, A, B) and five semitones (C#/D♭, D# / E♭, F# / G♭, G# / A♭, A# / B♭).

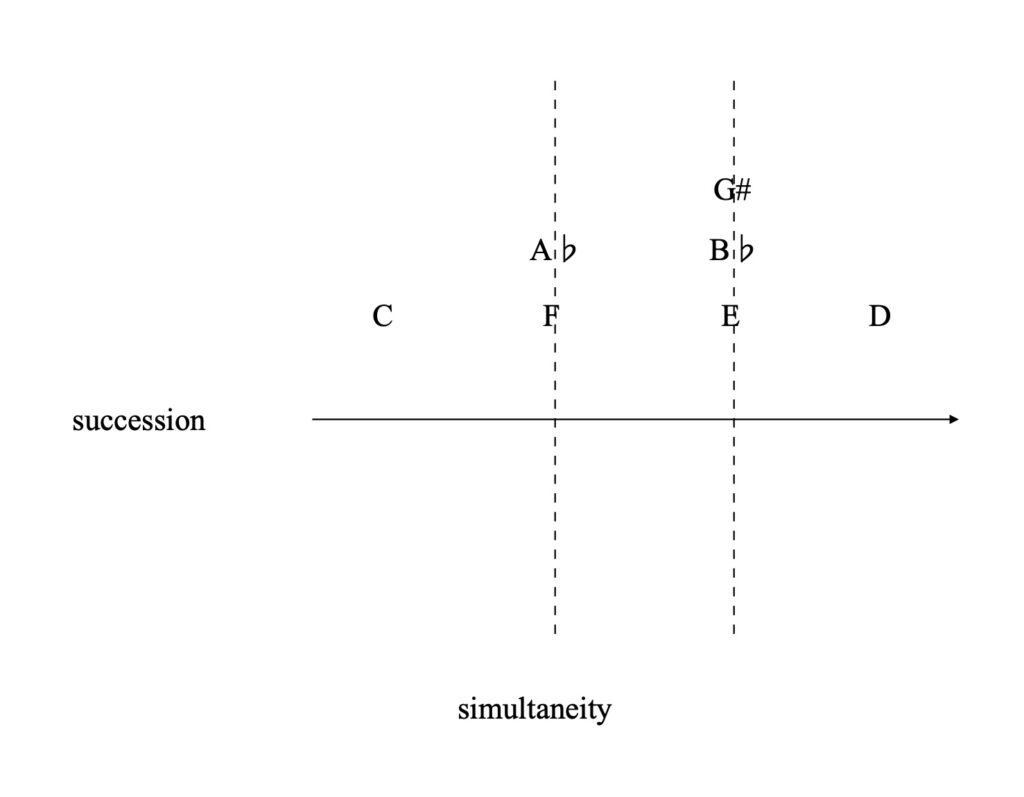

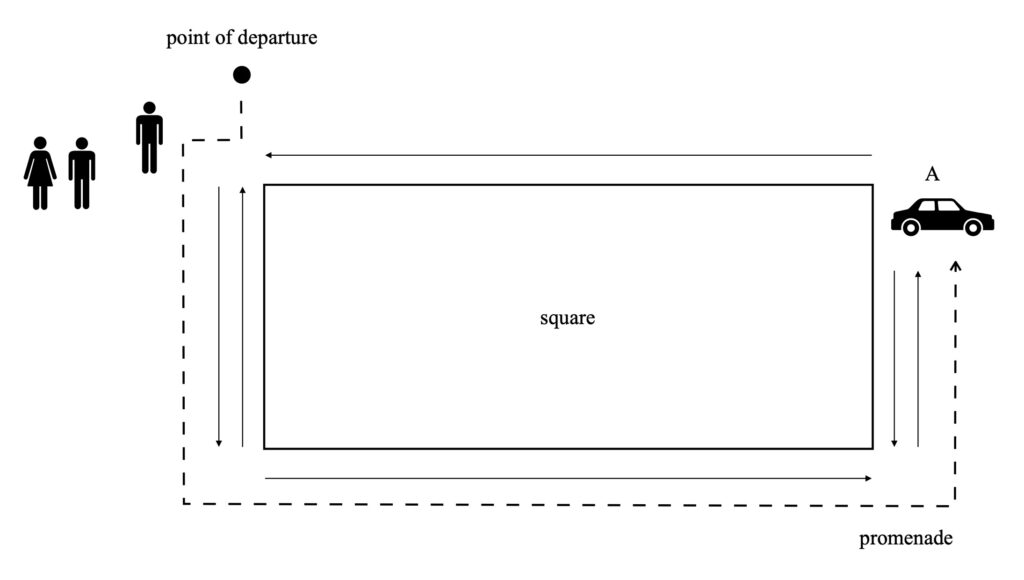

A first option (fig. 1) could be to select a few and distribute them randomly while allowing for some degree of simultaneity and succession:

Fig. 1. An almost-random distribution of a few musical notes

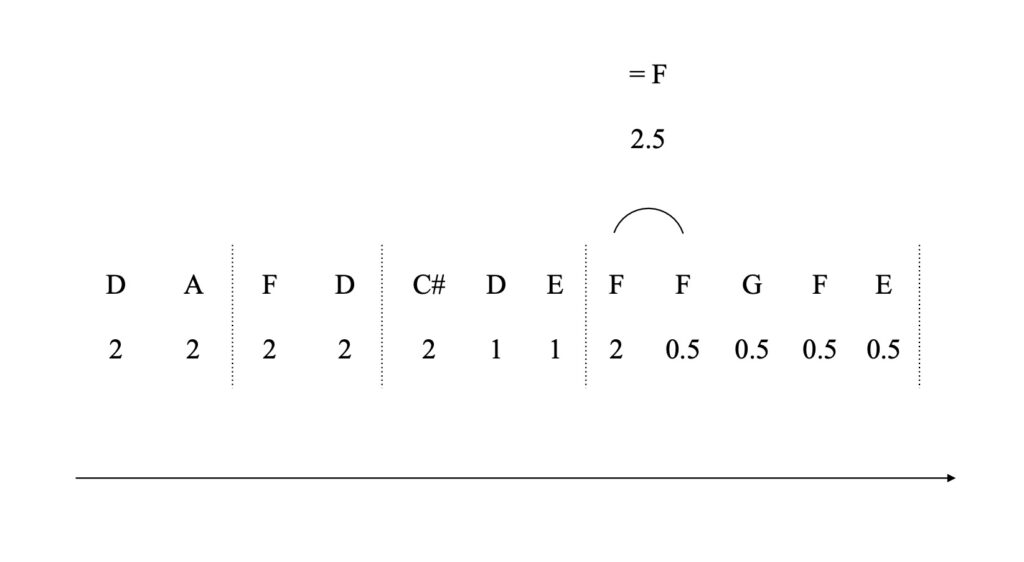

A more elaborate option (fig. 2) would be to form with them a melody, e.g.,

Fig. 2. A little melody

Here, moreover, each note is given a certain length (0.5, 1, and 2 seconds, respectively), and two of them are linked by a curved line, which implies that the transition between them, when played, should be imperceptible. For their part, the dotted vertical lines indicate that, according once more to their length, the notes are distributed within four rhythmic clusters that measure 4 seconds each.

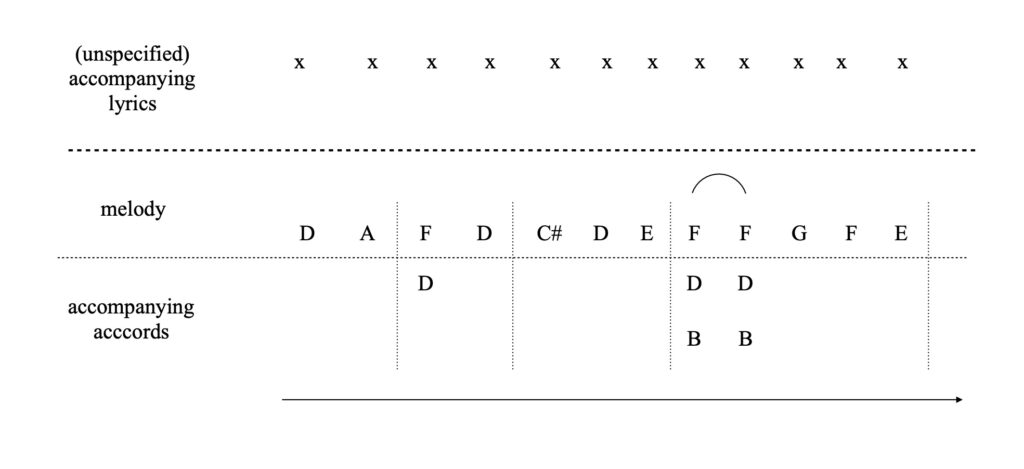

Now, one could play this little melody on a piano without any accompanying lyrics and/or accords. But one could also supplement it with these (fig. 3):

Fig. 3. The same melody, now accompanied

In the first case (unaccompanied melody) we would have what is called a monody. In the second case, we would have an accompanied melody.

Most of the music we are used to listen to is of this kind. Yet, there are other options, as well.

One of them is polyphony, a term that denotes the coexistence of many voices doing different things – not the very same thing (e.g., sing in unison the melody in fig. 3), as this would not be polyphony. In turn, the term counterpoint names a particular type of polyphony, one of its many possible formal variants.

I have mentioned that most of the music we are used to listen to is some kind of accompanied or unaccompanied melody. Thus, for example, medieval songs, Gregorian chant, any classical musical piece more or less cantabile (e.g., Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words) and the totality of pop songs fall under this category. Now, what does this mean? It means that, whatever one’s preferences, the same listening principle is at stake in them, i.e., that they all ask to be listened to inthe same way.

With polyphony and counterpoint, however, this changes: they require another way of approaching them, and this explains the difficulty that one may experience in listening for the first time to Bach’s Die Kunst der Fuge, can be far greater than the difficulty one might experience in enjoying Patti Smith proto-punk or The Rolling Stones’ rhythm and blues after having listened to Gregorian chant, and vice versa. For the different ways in which the sound material is organized in these three different musical genres, remain paradoxically closer to one another than to the way in which it is organized in Bach’s fugues (a fugue is a form of counterpoint). I am tempted to write that, in a certain sense, they are also closer to the ways in which the sound material is reorganized in serial or dodecaphonic music and to the ways it is disorganized in concrete music, both of which rebel against the primacy of melody (and harmony) in music. And I am also tempted to write that, for this reason, counterpoint is more of an alien phenomenon than even noise music – which in, in turn, anything but alien to us, as it merely reflects the world as we permanently hear it; you may well open the window to check it out.

II

According to The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music, a fugue is a “type of contrapuntal composition for particular number of parts or ‘voices’ (described thus whether vocal or instrumental, e.g. fugue in 4 parts, fugue in 3 voices)” where “the voices [first] enter successively in imitation of each other” and then develop (unlike in the canons, where their mutual imitation is considerably more strict) in different and relatively free yet interconnected ways.[1]

The fourteen fugues (one of them incomplete) and four canons of Bach’s Die Kunst der Fuge (The Art of the Fugue, BWV 1080), which is often regarded as his musical testament, likely represent, for their part, the peak of counterpuntal writing. Here is a beautiful interpretation, by Franco-Haitian pianist Célimène Daudet.

Inevitably, one gets the impression that, more perhaps than any other one of Bach’s, this work, with its fractalized subjects and mirroring counterpoints, pays homage to Leibniz’s monadology, according to which every single point of reality reflects differently the whole of which it constitutes but a part.

In §§ 56 and 57 of his Monadology, Leibniz writes:

56. [The] interconnection or […] accommodation of all […] things to each other and of each to all the rest, means that each simple substance [or monad][2] has relations which express all the others, and that consequently it is a perpetual living mirror of the universe.

57. The same town, when looked at from different places, appears quite different and is, as it were, multiplied in perspectives. In the same way it happens that, because of the infinite multitude of simple substances, there are just as many different universes, which are nevertheless merely perspectives of a single universe according to the different points of view of each monad.[3]

The same can be said of the subjects and counterpoints of The Art of the Fugue: they multiply the perspectives of a single universe according to different points of view. It is, therefore, the notion of a constant and manifold correlation between unity and multiplicity that vertebrates the whole work, while Leibniz’s monadology offers a suitable intellectual frame thereof.

It would be wrong, however, to suppose that the universe thus infinitesimally reflected in Bach’s fugues – and probably too in Leibniz’s philosophy, despite Leibniz’s apparent tendency to wrap it all up around a single stable axis[4] – is a closed world.

To begin with, its own infinitesimalness points in the opposite direction; so much so that one gets the impression that other possible variations could be added to those displayed in a work of which Bach himself produced different versions.[5] After all, some of the fugues and/or of the passages in the collection result from shortening the temporal intervals that separate the entrance of the voices in question, whereas others result from augmenting and diminishing the length of their notes, and it seems obvious that measures different from those explicitly explored by Bach.

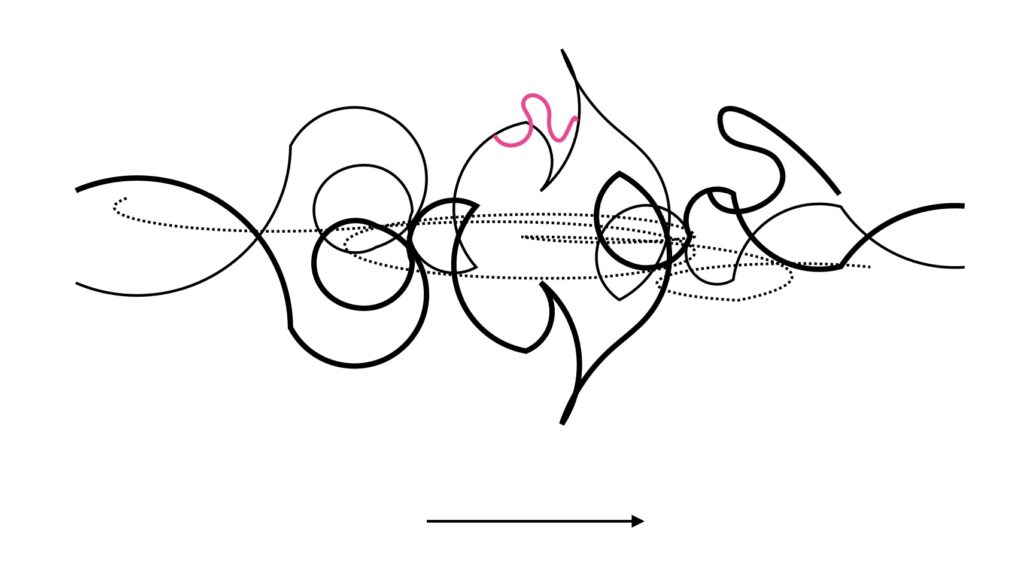

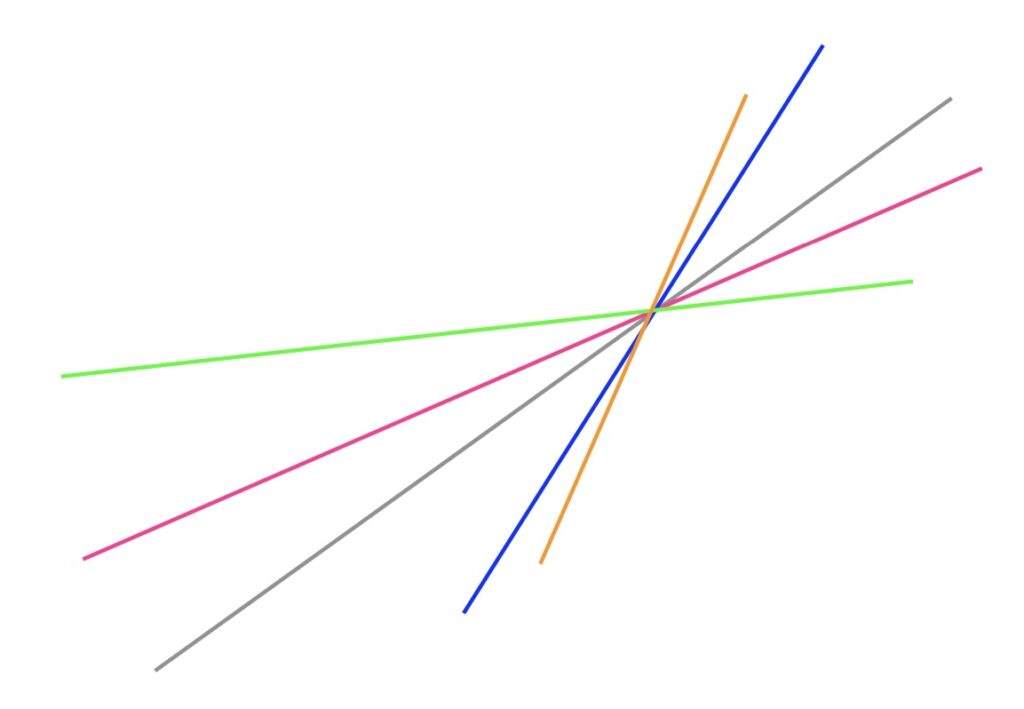

Secondly, one often comes across two types of molecular (in the Guattarian sense)[6] fleeting elements whose manyfold reflections form quasi-imperceptible but ever-growing cells similar to overlapping arches or to the intermingled splashes from a water fountain (fig. 4).[7] Consider, for instance, the first fugue (Counterpoint No. 1). In addition to a sea of voices whose surface gradually curls (or “ruffles,” as Joseph Kerman puts it)[8], or maybe not so much in addition to it as fleeing from it, an ample tonal interval (that is, a wide jump between two notes) recurs from the sixth bar onwards (it can be first heard after the fourth note of the second voice, once this one is introduced), and it does so with such pregnancy that one wonders whether everything else ultimately vanishes before it or, rather, behind it, in an extraordinary figure-ground reversal.

Fig. 4. The molecular fleeting element in Bach’s Counterpoint No. 1 (BWV 1080)

Other times, a tiny detached cell manages tosurfacefrom within, and to ephemerally but beautifully surf through, the implacable waves formed by the criss-crossing of the many intersecting voices, as though a little fish could become visible and momentarily fly over these only to become, in the next instant, foam swallowed back by them. This is easily perceptible, for no more than three seconds, at minute 01:40 of Counterpoint No. 5: an little unannounced ritornello, very much moving, vectorizes itself at that point and then disappears leaving no trace.

Fig. 5. The molecular fleeting element in Bach’s Counterpoint No. 5 (BWV 1080)

But it can also happen that another tiny detached cell reappears miraculously elsewhere, where and when one would not expect it. An attentive cross-listening of Counterpoint No. 8 and Counterpoint No. 14, whose subject is different from the subject developed by all other counterpoints in the collection, hints at this unpredictable mirror effect, whereas several other counterpoints (e.g., nos. 1, 4, 12, 13) explore more structurally predictable, yet not less thrilling, mirroring effects.

In short, not only is the nanoscopic is variously raised, here and there, to the main role: it paves the way to openness. And this not to speak about the incompleteness of last fugue (Counterpoint no. 14), which Bach could not finish because death surprised him working on it, for which reason we cannot fancy how he might have ended it, despite some interesting attempts at figuring it out (e.g., Davitt Moroney’s); or about the fact that no he provides no indication whatsoever as to the instrumentation more suitable for the collection (organ? harpsichord? string ensemble? other?)

III

Again: accustomed, as we are, to listen to essentially melodic tunes, whether accompanied or not, Bach’s latest fugues might prove somewhat alien to our sensibility; even in comparison to earlier fugues of his like, say, the central piece of his Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro, BWV 998 (originally written perhaps for lute-harpsichord) or fundamentally contrapuntal works like the Goldberg Variations, BVW 988, on which I have recently written here, also in connection to Leibniz’s philosophy.

And yet, it may well be that dreams are not so different after all, that they, too, run like fugues through our unconscious, provided that they can be mapped – rather than interpreted, but more on this difference below – according to alter-structural principles which, nonetheless, leave room for contingency in them.

Guattari’s supplies a wonderful example thereof.

In the first of the appendixes to his Schizoanalytic Cartographies,[9] Guattari not only plays with Bakhtin’s notion of “polyphonic lines”[10] and “sequences”[11]; he speaks, too, of the possibility of undertaking “a polyphonic analysis of [a dream’s] lines of subjectivation”[12] in relation to a dream of his which he thus offers as an example.

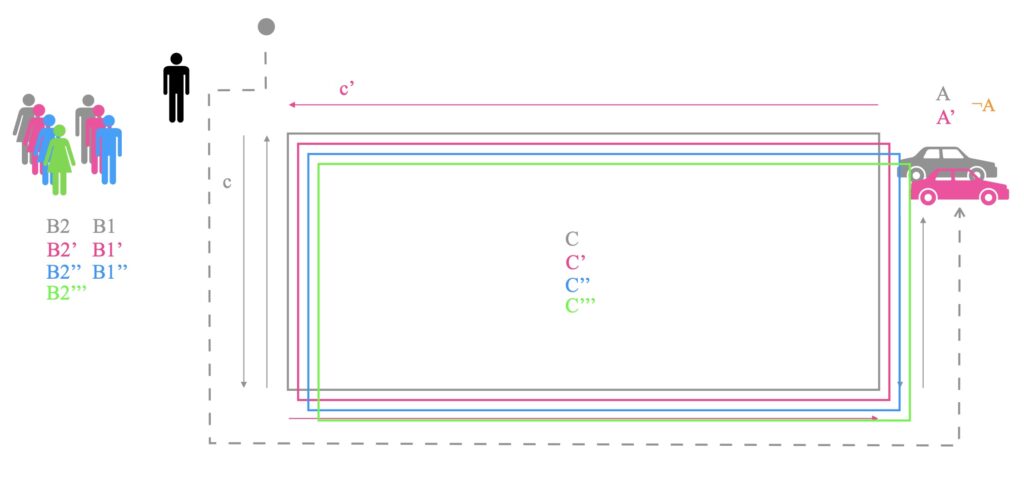

Overall, the tangible components of the dream in question – in which he dreams of himself trying to recover, in the company of a couple friends of his with whom he had spent the evening, his car, that he had supposedly parked somewhere nearby, but whose precise location he had apparently forgotten – are:

| A | The forgotten car (which is his) |

| B | The friendly married couple: (B1) a man and (B2) a woman |

| C | A rectangular square (near which he thought at first to have parked the car) |

Table 1. Main subjects in Guattari’s “A.D.” dream

Yet three additional, intangible, components ought to be added to these, namely:

| X | A certain anguish he feels because of having forgotten his car |

| Y | A lapsus he has towards his friend when he thanks him for having guided him back to the place where he thought he had parked his car (which puts an end to his anguish) |

| Z | A hesitant gesture he has towards the man’s wife when they farewell, so as to avoid making the husband jealous |

Table 2. Additional components in Guattari’s “A.D.” dream

It would be possible to label A, B, and C as the dream’s main themes or subjects. Now, they all undergo variations (A’, B’, C’…) – or else must be viewed themselves as variations.[13] Plus, the same applies to component Z. Finally, C decomposes into a sub-theme (c), relative to the directions of the streets bordering the square, while A reverts into an anti-theme: (¬A) actually, he had not forgotten the car, as that evening he had gone by foot!

| A | Is it a Renault (Guattari’s current car at the time)? |

| A’ | Or is it rather a BMW (a car Guattari had a few years back)? |

| B | Is it (B1) Yasha David (a specialist in Kafka, responsible of an exhibition latter at the Pompidou on the occasion of Kafka’s centenary, and with whom Guattari had fruitfully collaborated thereof) and (B2) his wife? |

| B’ | Or is it rather (B1’) Jean Gallard and (B2’) his wife Héléna Gallard (a friend of Guattari), that is to say, a different couple (which Guattari liked very much)? |

| B’’ + (again) A & A’ + Z & Z’ | Or is it neither (B1) Yasha David nor (B1’) Jean Gallard but (B1’’) Deleuze, who had been also at the Pompidou and whose name Guattari is (Y) about to pronounce in his dream when he hugs Yasha David when he feels released from (X) his former anguish? Interestingly, if it were to be Deleuze, this could explain A → A’, i.e., Guattari’s mixing of (A) the Renault he then owned with (A’) the BMW he had had a few years back, when he began collaborating with Deleuze. Back then, though, Guattari lived with a woman, Arlette Donati, vis-à-vis whom he felt jealous. Is it, then, that (Z) he fears Yasha David to be jealous (for he has been told David is) if he greets his wife effusively when departing? Or is it that (Z’) it is his own jealousy that is disguised as his friend’s. |

| B’’ & B’’’ | Furthermore, can the name of (B2’’) Arlette Donati be just a clue to that of (B’’’) Adélaïde, a woman with whom Guattari was amorous at the time in which he had the dream and whom he usually called A.D.? (As with Arlette Donati, their relation also proved problematic.) |

| C | As for the rectangular square, which square is it? Is it just the square nearby which he thinks to have forgotten the car? |

| C’ | Or is it Michoacan’s? |

| C’’ | Or is it an old square in Louviers, where he lived some time with his grandmother a good many years back? |

| C’’’ | Or is it a square in Mer, nearby which he currently stays half of the week? |

| C’’’’ | Or is the square an image of Guattari’s own schizoanalytic fourfold?[14] |

| c & c’ | And why is it, anyway, that in order to retrieve his car he had to go around almost all the square and that the streets bordering it were (c) two way (those bordering its two shortest sides) or else (c’) go one way but in opposite directions (those bordering its two longest sides)? |

| ¬A | Lastly, what does it mean that, in the end, Guattari realizes he had gone by foot that evening, not by car? |

Table 3. Contrapuntal variations on the subjects of Guattari “A.D.” dream

Each subject does not only divide, therefore, in several variations: these can be described, literally, as their counterpoints at different heights. Hence, either during the dream or through its analysis,

- the presence of A’ and ¬A behind or before, underneath or above A, as if they formed three opposing mirrors;

- that of B’, B’’, and B’’’ behind or before, underneath or above B, as if they formed four opposing mirrors;

- that of C’, C’’, C’’’, and C’’’ behind or before, underneath or above C, as if they formed five opposing mirrors;

- that of c’ next to c, as if they formed two opposing mirrors; and

- that of Z’ behind or before, underneath or above Z, as if they, too, formed two opposing mirrors

become patent – they compose, says Guattari, a series of “harmonic constellations of levels of enunciation”[15] or recursive metaphors[16] that coexist and must be deemed, as we shall see, open-ended. Put otherwise, here too the variations of each subject run in imitation of each other; plus, here too they intertwine and develop, more or less freely, in different ways.

Besides, those many mirrors fold ultimately into two temporal mirrors that reflect each other, each of which corresponds to one of the years at stake in the dream (one latent, the other one manifest):

1968 | 1984

“Everything is as if the initialling of the period 1968 climbed back up to 1984, passing from Arlette Donati to A.D. (Adelaide),” writes Guattari[17] – in a sort of mirror fugue in which each period therefore chases the other one, one may add, for at first it is the present (1984) that dives or runs backwards into the past (1968). If we were to add to it the three pairs of key-figures thus involved, we would get the following table:

| 1984 | Renault | A.D. | Yasha David |

| 1968 | BMW | Arlette Donatti | Gilles Deleuze |

Table 4. The two mirroring time periods in Guattari’s “A.D.” dream. (Guattari’s own table[18])

Accordingly, it is possible to map the dream as follows:

Fig. 6. Cartography of Guattari’s “A.D.” dream (subjects). Cf. Guattari’s own diagram [19])

Fig. 7. Cartography of Guattari’s “A.D.” dream (variations)

Just like a fugue is made of a subject (or more than one subject) and its (or their) contrapuntal variations chasing one another, the “dream of A.D.,” as Guattari calls it, is made of several subjects and their variations in counterpoint.

As for A and ¬A (had he really forgotten the car, had he not?), those two components highlight in turn, metaphorically speaking, the problem of one’s self-analysis (auto[= French for “car”]–analysis!)[20] – and probably too the need to undertake the latter as a thorough mapping (after all he had gone, and ought then to return, by foot!) of the subjectivation lines served by the dream and of the questions they posit; instead, that is, of identifying the analytic object (a dream in this case) as the symptom of a pre-determined psychological complex or archetype. In fact, the difference between traditional psychoanalysis (whether Freudian, Jungian, or Lacanian) and Guattarian schizoanalysis lies there.

“When I first came to live among the Daribi [of Papua New Guinea], one of the most common explanations given to me to excuse the early-morning absence of an informant was that ‘he had a dream’ and had gone hunting. Generally Daribi men regard a good hunting dream as an opportunity not to be missed, and take immediate action on it. Dreams are usually felt to be prophetic and are often mentioned in myths as revealing some secret or hidden danger to the hero,” writes Roy Wagner[21]. Furthermore, while for the Daribi – like for most extra-modern peoples – magic creates capabilities that, says Wagner, pull different pragmatic fields into alignment, dreams reveal possibilities that prove apt for such undertaking.[22] In other words, instead of enclosing their dreams within the sounding board of a single resonant signifier (again, such or such complex or archetype), the Daribi engage in what can be properly called a pragmatics of dreams which is also that of Guattarian schizoanalysis.[23]

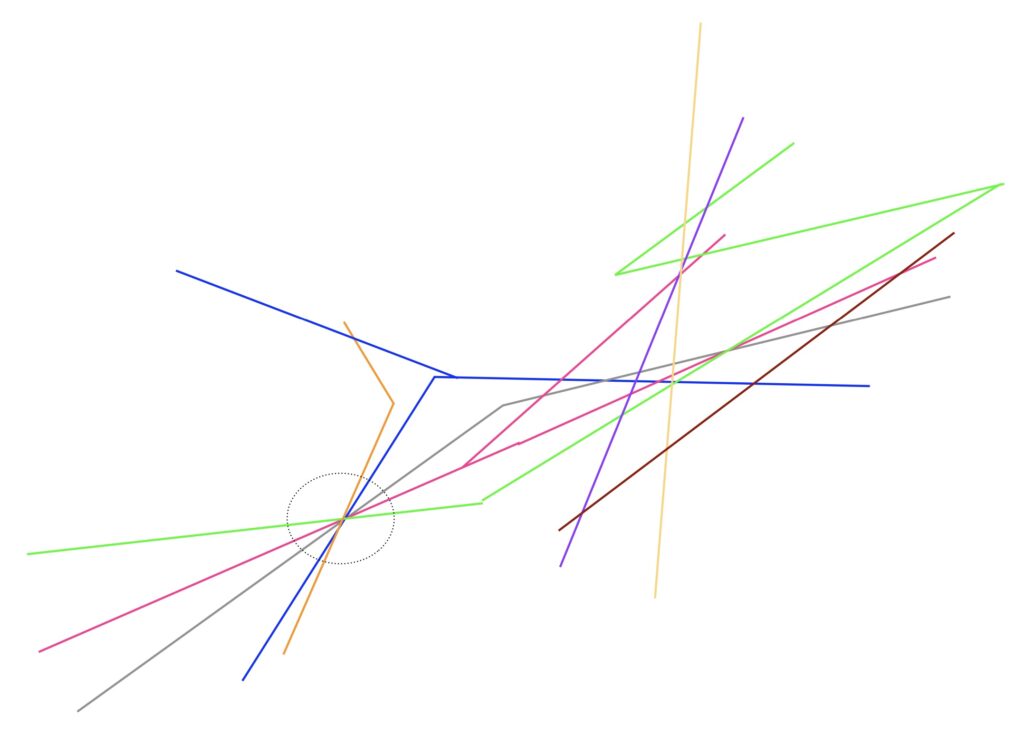

Now, it is paramount to stress at this point that, from a schizoanalytic perspective and despite their apparent coherence, dreams remain – like Bach’s fugues – open-ended. For, more often than not, the different lines of subjectivation that shape it according to a principle of homology, lines which thus co-incide in it (fig. 8), may well co-incide elsewhere, that is to say, in other dreams, and do so in a different pragmatic context (fig. 9).

Fig. 8. Guattari’s “A.D.” dream: restricted geometrical composition

Fig. 9. Guattari’s “A.D.” dream: expanded geometrical composition

Contingency is thus granted a major role here.[24] Moreover, it would be likewise possible to depict such or such dream as per the geometrical drawings ventured in figs. 4 and 5. above, e.g. a dream with an initially overlooked and seemingly minor yet recurring core leitmotif that may also recur elsewhere, or a dream in which a little but key fleeting element rises from the tide opening onto a new world of possibles; and all of it while the flowing waves that make and unmake reality criss-cross endlesly.

In short, dreams may be said to behave like fugues within the field of the unconscious…

c.

* * *

Notes

[1] Michael Kennedy, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music (4th ed.; Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 271. On the semantics of the noun “fugue,” see Paul Mark Walker, Theories of Fugue from the Age of Josquin to the Age of Bach (New York and Suffolk, UK: University of Rochester, 2000), p. 348: “Because of its original non-musical meaning of chasing or fleeing, ‘fugue’ [is] associated with imitative counterpoint.”

[2] Derived from the Greek monas (“unity”), the term monad denotes something that stands alone because of being one and only, i.e., “unique” (monos). The world is, according to Leibniz, a collection of monads or simple substances which must be viewed as perceptive and acting entities rather than as purely material substances.

[3] Lloyd Strickland, Leibniz’s Monadology: A New Translation and Guide (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), p. 25.

[4] Can one read it otherwise, though? What if the Leibnizian need to somehow bring all things together were just to express the need to somehow bring meaningfully all experienced things together?

[5] See Anatoly P. Milka, Rethinking J. S. Bach’s The Art of the Fugue (London and New York: Routledge, 2017).

[6] There is, writes Guattari, a “[m]olar order [that] corresponds to the stratifications which delimit objects, subjects, their representations and their systems of reference,” and a “[m]olecular order” which is, in contrast, “that of flows, of becomings, […] of intensities” (Félix Guattari, Molecular Revolution: Psychiatry and Politics [trans. R. Sheed and D. Cooper; London and New York: Penguin, 1984], p. 289).

[7] Like Lévi-Strauss’s canonical formula of myth, which does not aim at arithmetical exactness, these diagrams do not aim at geometrical exactness either: they want to be suggestive of something that, no doubt, could be drawn differently. On the pertinence of these type of visual metaphors, anyway, see here. As for the value of metaphors, more broadly, I have examined the issue here.

[8] Joseph Kerman, The Art of the Fugue: Bach Fugues for Keyboard, 1715–1750 (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), p. 33.

[9] Félix Guattari, Schizoanalytic Cartographies (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2013), pp. 191–202.

[10] Ibid., p. 199.

[11] Ibid., p. 195.

[12] Ibid., p. 196 (trans. slightly modified). By “subjectivity,” Guattari understands what we are and what we can become in relation to the world, as well as the various dynamic process (pathic, synaptic, modal, temporal, etc.) involved in it.

[13] As in Lévi-Strauss’s Mythologiques, where there is no source myth, but all myths reflect one another, and thereby tend to coincide infinitesimally, in the lack of any underlying paradigm. “The science of myths might therefore be termed ‘anaclastic,’” writes Lévi-Strauss, “if we take this old term in the broader etymological sense which includes the study of both reflected rays and broken rays” (Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Raw and the Cooked: Introduction to a Science of Mythology, Volume 1 [trans. J. and D. Weightman; New York: Harper & Row, 1969], p. 5).

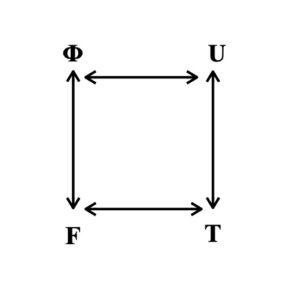

[14] I.e.,

Fig. 10. Guattari’s four-functors (a very basic depiction).

where where “F” stands for any given Flows of desire, energetic, material, and signaletic (rather than narrow libidinal drives); “Φ” for the Phyla or relatable sets of existing diagrammatic connections (cognitive, informational, etc.) that those flows happen to intersect with; “U” for the Universes of reference (rather than unconscious complexes) emerged from such intersections; and “T” for the resulting existential Territories (rather than personological instances) that they delimit.

[15] Guattari, Schizoanalytic Cartographies, p. 199.

[16] I have coined this term in a study on the baroque nature of Yaminahua shamanic songs, titled “Metaphoric Recursiveness and Ternary Ontology: Another Look at the Language and Worldview of the Yaminahua” (Tipití: Journal of the Society for the Anthropology of Lowland South America, vol. 17, no. 1 [2021]: pp. 66–82).

[17] Guattari, Schizoanalytic Cartographies, p. 199.

[18] Ibid., p. 192.

[19] Ibid., p. 199.

[20] bid., p. 195.

[21] Roy Wagner, Habu: The Innovation of Meaning in Daribi Religion (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1972), p. 98.

[22]. Ibid., p. 99.

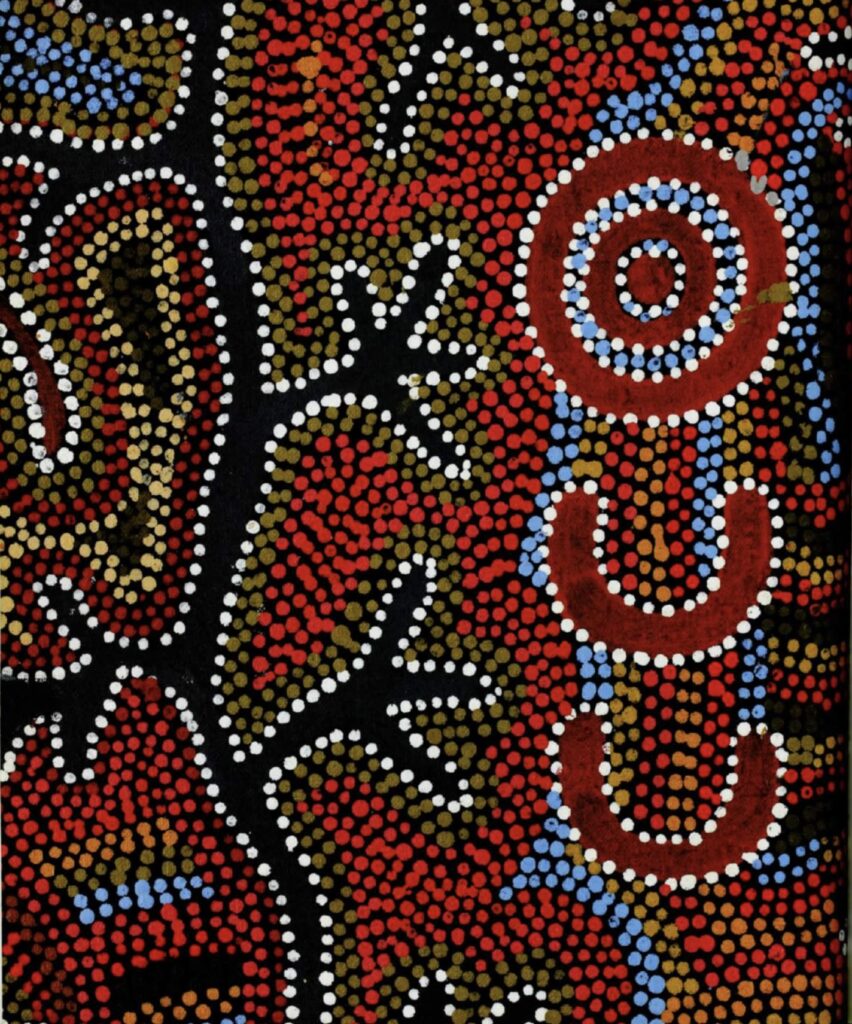

[23] In the case of the Warlpiri and other Australian Aboriginal groups, the pragmatics of dreaming are extensive to other-than-human beings, as well; dreams, consequently, form a world wide web of which human dreams are but a parcel. See, e.g., Barbara Glowczewski (whose work considerably influenced Guattari), Desert Dreamers: With the Warlpiri People of Australia (Minneapolis: Univocal, 2016). The following painting (taken from Philippe Descola, ed., La fabrique des images. Visions du monde et formes de la représentation [Lyon: Musée du qui Branly/Somogy, Éditions d’Art, 2011] p. 138) shows a Warlpiri crossroad-like dream:

Fig. 11. “A Fire’s Dream Traversed by an Emu’s Dream” (Warlpiri painting)

[24] Borges has written admirably on oneiric superimpositions, yet often under the sign of fatalism: “One day or one night – between my days and nights, what difference can there be? – I dreamed that there was a grain of sand on the floor of my cell. Unconcerned, I went back to sleep; I dreamed that I woke up and there were two grains of sand. Again I slept; I dreamed that now there were three. Thus the grains of sand multiplied, little by little, until they filled the cell and I was dying beneath that hemisphere of sand. I realized that I was dreaming; with a vast effort I woke myself. But waking up was useless – I was suffocated by the countless sand. Someone said to me: You have wakened not out of sleep, but into a prior dream, and that dream lies within an other, and so on, to infinity, which is the number of the grains of sand. The path that you are to take is endless, and you will die before you have truly awakened” (Jorge Luis Borges, Collected Fictions [trans. Andrew Hurley; London and New York: Penguin, 1999], p. 252).