In what follows, we render all indigenous terms in curly brackets to remind the reader that indigenous languages were, originally, non-written languages. This does not mean they were simpler, though. The fact that many indigenous languages are polysynthetic, for instance, makes them complex to an extreme which is hard for us to even fancy; thus a single verb in Amuesha, an Arawak language from South-America:

{ø-omaz-amy-eɁt-ampy-es-y-e.s-n-e.n-a}

means: “they are going downriver by canoe in the late afternoon stopping often along the way.” In some languages like Iatê, a Macro-Jê variant, nominal phrases and even nouns have grammatical tense (i.e. they can be specified as naming something past or future) while nouns can be specified too considering their degree of reality (a “former house” being more real than “what could have been a house,” for example). Also, in Pirahã, from the Mura-Pirahã language family, the language can be either spoken, sang, or whistled, whereas many languages like e.g. Pastaza Quichua have abundant (c. 1,000) regular ideophones that “communicate through imitative simulations the vivid impressions of sensory experience […] including bodily processes, configurations, cognitive capacities, movements, sounds, and proprioceptions” as well as non-human “reaction to being acted upon by humans.”(*) And to almost close this short list of remarkable features to which many more could be easily added one may note too that Karajá, another Macro-Jê language, has a phonological gender-based speech distinction, while in Kadiwéu, a southern Circum-Amazonian language belonging to the Guaicuruan family, men and women often use different words for the same things. Lastly, we would like to emphasise that Panoan languages present morphological possibilities which are unique in the world and that Karawanka speakers – to move now from South- to North-America – held back their breath while speaking, releasing it at the end of each sentence with a heavy exhalation and never looked at the person to whom they were speaking.

***

The Aché define {bayja} as the personal quality or power that a man has to “attract living creatures.”(*) Only men (i.e. the hunters in the group) can be affected by {bayja}. They are strongly affected by it when their spouses give birth. Thus when the man whose wife has just given birth goes hunting on the next day, it is taken for granted that he will return to the village with something. “We know. That’s the way it is…,” say the Aché. Is {bayja}, then, as a superstition, a belief the Aché irrationally cling to? It is something far more complex and altogether different indeed.

As Pierre Clastres writes,

The Guayaki divide animals into two main classes: there are the animals normally hunted by the Indians (monkeys, armadillos, wild pigs, roe bucks, etc.) and then there are the jaguars. Jaguars are the first to discover that there is a man in a state of {bayja} in the woods, and the Indians say, “{Ache bayja bu baipu tara iko}. When a Guakaki is bayja, Jaguars come in great numbers.”

Who are the jaguars to the man?

They [are] the threat that weigh[s] on him, and he [can] overcome it only by killing one or more animals. In other words, if the man does not fulfill his role as a hunter […] he himself w[ill] become the prey of that other hunter, the jaguar.

The man, therefore, has two alternatives: to die like a pray or to kill like a hunter.

This is the effect of the {bayja}: it provides the man it infects with the means to reaffirm . . . [himself] by giving him the power to attract animals, but at the same time it increases his danger because of the many jaguars who will approach him. To be {bayja} therefore means to live in ambiguity.

Nevertheless, this ambiguity – and, ultimately, then, the danger that threats the hunter – reflects the unsteadiness of his ontological situation. This, in fact, is the main point of it all:

In reality, he walk[s] […] in quest of his own self […] [because] he [has been] […] put to death, even though symbolically, [by the birth of his son].

Why? Because the joining of the world and the child, as Clastres says, signifies the separation of the world and the father:

The father and the child cannot live together on earth. The jaguars, bearers of death and messengers of the child […] fulfill a destiny unconsciously thought out by the Indians as a form of parricide: the birth of the child is the death of the father. […] Even if the father escapes the jaguar by killing an animal, symbolically he has already been sentenced to death by the birth of his child […] [since] men are not eternal.

There is a curious “meeting ground” here, adds Clastres, between indigenous and early-Greek thought:

The Indian and the philosopher share a way of thinking because, in the end, the obstacle to their efforts lies in the sheer impossibility of thinking of life without thinking of death.(**)

Put differently: {bayja} is, for the Aché, the notion they have (invented) to capture the co-presence of life and death, and more specifically the closeness of death for those who give life, for by giving life they are reminded of their own approaching death.

It is, then, a notional “centre of vibrations” that allows life and death to simultaneously resonate and vibrate in their minds qua existential vectors. And, therefore, as per Deleuze’s definition of what a “concept” is,(***) it is a concept. Purely and simply. A concept then, not a belief, let alone a superstition.

Besides, indigenous concepts often prove to be astonishingly rich in semantic terms. Thus, for instance, while we have three basic expressions to denote “transgender” people: “transgender,” “transexual,” and “non-binary,” the number of words for it among the different North-American aboriginal languages, or even among one single language among these, is greater and thus far more nuanced, e.g. {nádleeh}, “one who changes” (Navajo), {iskwêhkân/napêhkân}, “one who lives as a woman/man” (Cree), {winyanktehca}, “one who wants to be like a woman” (Lakota), {ninauh-oskitsi-pahpyaki} “manly-hearted woman” (Niitsitapi), or {înahpîkasoht} “someone who fights everyone to prove they are the toughest” (Cree), to merely mention a few terms.

(*) Janis B. Nuckolls, “Ideophones in Bodily Experiences in Pastaza Quichua (Ecuador)” (paper presented to the 2011 Symposium for Teaching and Learning Indigenous Languages of Latin America (STLILLA), University of Notre Dame, Indiana, October 30–November 2, 2011), pp. 0, 3.

(**) Pierre Clastres, Chronicle of the Guayaki Indians (trans. by Paul Auster; New York: Zone Books, 1998), pp. 35-37, 40-41. Clastres has in mind Heraclitus, in particular.

(***) Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, What Is Philosophy? (trans. by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchell; New York and Chichester, UK: Columbia University Press, 1994), p. 23. Despite the official attribution to Guattari as well, book is known to be Deleuze’s alone (unlike the two coauthored volumes of Capitalism and Schizophrenia: The Anti-Oedipus and A Thousand Plateaus, and Kafka: Towards a Minor Literature).

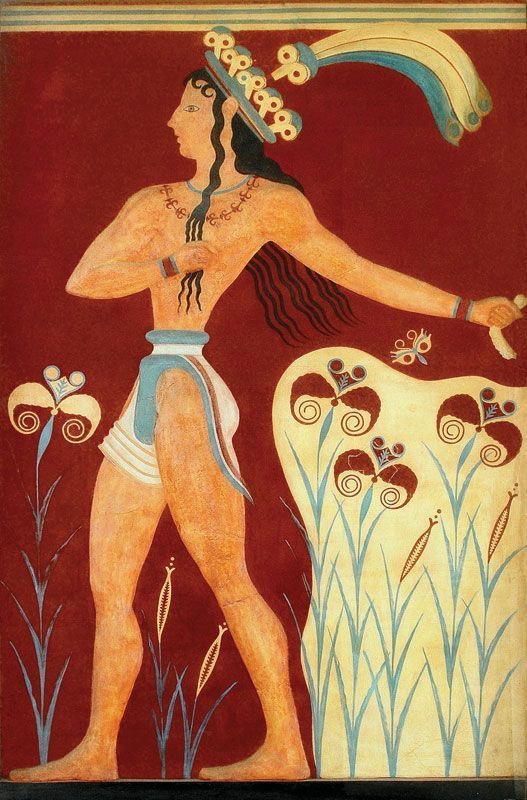

A (Pre-Hellenic) Minoan man, from a fresco in Knossos (Crete), Europe’s oldest city, whose “dress” somehow reminds us that we were all indigenous peoples once. There still is, moreover, an indigenous person in all of us, since our languages, by which the world opens to our experience, are ultimately rooted in the indigenous languages we once spoke (on which see further here).