The Yanomami myth of the “falling sky” – which resembles that of the Celts reported by Ptolemy to Alexander during his campaign in Thrace against the Illyrians – offers a perfect site to briefly explore the relationship between metaphor and meaning. Davi Kopenawa narrates the myth thus:

At the beginning, the sky was still new and fragile. The forest had barely come into existence and everything there easily returned to chaos. It was inhabited by other people, who were created before us and have since disappeared. It was the beginning of time, during which the ancestors changed into game one after another. And when the sky’s center finally collapsed, many of them were hurled into the underworld. The back of this sky that fell in the beginning of time is now the forest where we live and the ground that we walk on. This is why we call the forest […] the old sky […] the […] ancient celestial layer. Later another sky came down and fixed itself above the earth, replacing the one that had collapsed. […] Our shaman elders know all this. As soon as the sky starts to shake and threatens to crack, they instantly send their xapiri [spirits] to reinforce it. Without that, it would have collapsed long ago.(*)

Like those of other Amazonian cultures, the Yanomami universe is profuse in pre-cosmological metamorphoses by which a number of all-human primordial beings changed into various kinds of non-human beings. Each stable resulting combination, i.e. all worlds that have come out of the primordial chaos, comprise a ground below and an upper domain above it: an earth and its corresponding sky, or a sky and its corresponding earth.

As it happens in so many Amerindian and non-Amerindian cultures alike, it is the sky that treasures the principles out of which the earth’s beings take shape; hence the opening lines: “At the beginning, the sky was still new and fragile.The forest had barely come into existence and everything there easily returned to chaos.”

Besides, the Yanomami think that all worlds come to an end, and that a new world always rises upon the remains of the preceding world. But how does this happen? It takes place as follows: The sky of the world that is coming to an end collapses, given that the values of any world must decline for that world to become effectively extinct. And on the back of that collapsed sky a new earth surges, as any new world must be based on new values which are necessarily located “on the back” (i.e. out of sight) of the values replaced by them. Therefore, each fallen sky becomes the ground on whose back a new world emerges.

The logic of the myth is faultless. We are before a fully-rational myth. Yet the recourse to metaphor in the myth demands that the question be asked about the relation between meaning and metaphor. Does metaphor merely serve to illustrate meaning – that is, does the myth refer to something else? Or does it produce meaning as such – so that the myth can be deemed to be meaningful on its own? The primacy of the myth over its explanation, of which the transmission of the myth alone is the proof, militates in favour of the latter option.

(*) Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman (translated by Nicholas Elliott and Alison Dundy; Cambridge [MA] and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013), pp. 130-131.

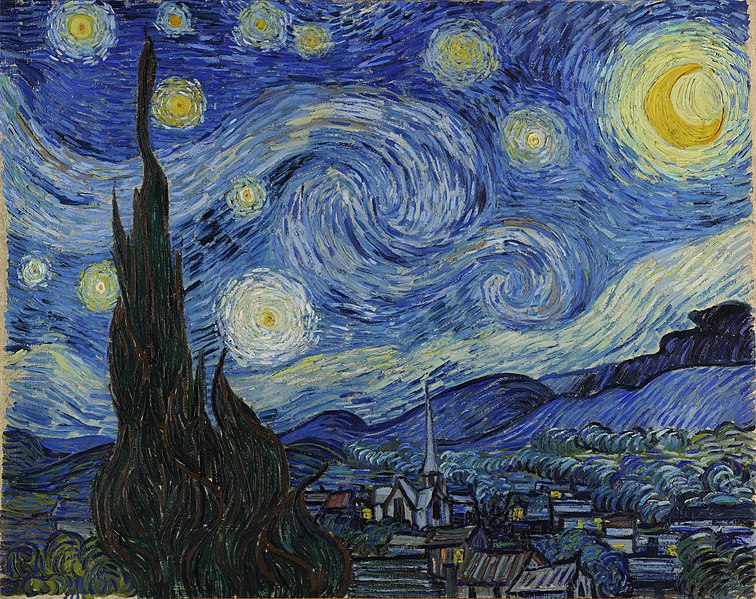

Vincent Van Gogh, The Starry Night (1889). Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York.