We have written elsewhere on schizophrenia, following Jean Oury, as a “rhythmic distortion.” We would now like to add that such distortion is neither what one presences when one witnesses a schizophrenic delirium nor what one enters when one enters one. For, as Freud stresses, it is at re-building their collapsed worlds that psychotics aim by displaying what we reductively call their “delirium.”

Francesc Tosquelles offers a moving example of this in an exchange with one of his patients:

Patient. – I’m broken, I’m not detached, I’m not broken, I’m like you; suddenly I thought I had died, but I’m here now.

Analyst. – How did it happen – your death?

Patient. – All of a sudden; we’ve all disappeared.

Analyst. – And what are you doing now?

Patient. – Always waiting.

Analyst. – What?

Patient. – I don’t know.

Analyst. – Who are you?

Patient. – I don’t know.

Analyst. – Who are you?

Patient. – The creator, the builder, the creator.

Analyst. – What have you created?

Patient. – Everything, the world.

Analyst. – And you?

Patient. – Me too, yes. I’ve brought myself into being, which is most absurd… and yet it’s true… I can’t stop thinking about it; otherwise nothing would be, there would be no food, no people, no ice, no winter…

The patient oscillates at the outset: first s/he admits to be torn apart – but then no, s/he says s/he is neither torn apart nor detached from the world in which, presumably, the doctor (and everyone else?) lives: s/he thought s/he was dead, but only to later realise (i.e. now, present tense) that s/he is there “like you” (like the “doctor.”)

Next oscillation: after describing how it all happened, how her/his world collapsed (all of a sudden and carrying down with it whoever was part of it: “we all disappeared”); and after being, immediately afterwards, unable to respond to the question about her/his identity (“Who are you?” – “I don’t know”), when s/he is asked the same question again (“Who are you?”) s/he then responds: “I‘m the creator, the constructor, the creator.”

What has s/he created?, inquires the “doctor.” “Everything,” the patient replies, “the world.” “And you?,” asks the doctor, “what about you?” “Me too,” s/he adds, “I’ve created myself.”

These words testify to an extraordinary display of creativity in an attempt to restore the world whose collapse the patient has experienced.

Otherwise, s/he suggests, how could anything at all take place?, how could one eat?, how could there be people?, how could there be ice?; and – by a straightforward association of ice to the winter, or perhaps by reverse association of the latter to the icy surface of a mirror that, when looked upon, shows back no face (since both terms, ice and mirror, are said in the same way in French) – how, then, could there be winter?

Notice the poetic qualities of these comparisons. The “imaginary world,” which the schizophrenic activates in her/his delirium to get cured is therefore, as Oury puts it, an imaginary “aesthetic” domain, or, in other words, a “metamorphic space” charged with new existential valences and ontological possibilities. By entering it, the schizophrenic returns to the “nascent” state of which her/his illness represents the distortion, and in this way tries to re-build a possible world – unless the delirium becomes chronic of course, which can also happen.

But if s/he manages to, s/he will successfully replace existential vertigo by existential rhythm, and eventually extract from the latter at least some forms.

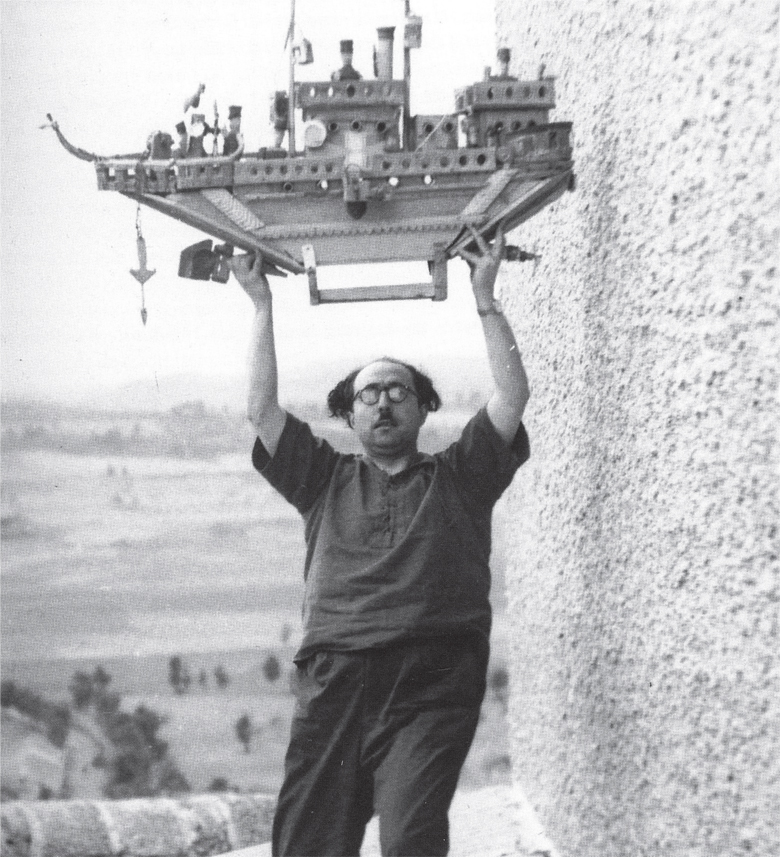

Francesc Tosquelles on the roof of the Hospital of Saint-Alban with a ship made by Auguste Forestier, May 1948. Archive Tosquelles. / Photography: Romain Vigoroux.