I

Curves, Concavities, and Pottery Bowls

The following drawing (which we have adapted from Paul Klee’s notebooks) represents the earth before any name is given to what the earth contains and, consequently too, before any distinction is made about its components (solids, liquids, and gases; obscure and bright things, long and short and hard and soft objects with rough or smooth textures; rocks, plants, and animals, etc.):

Figure 1

Suddenly, our (human) mind grasps two elemental “ideas” and their corresponding “forms” (and vice versa) in one of the regions of the earth’s mesh:

1) a “curve”:

Figure 2

and thereby 2) a “concavity”:

Figure 3

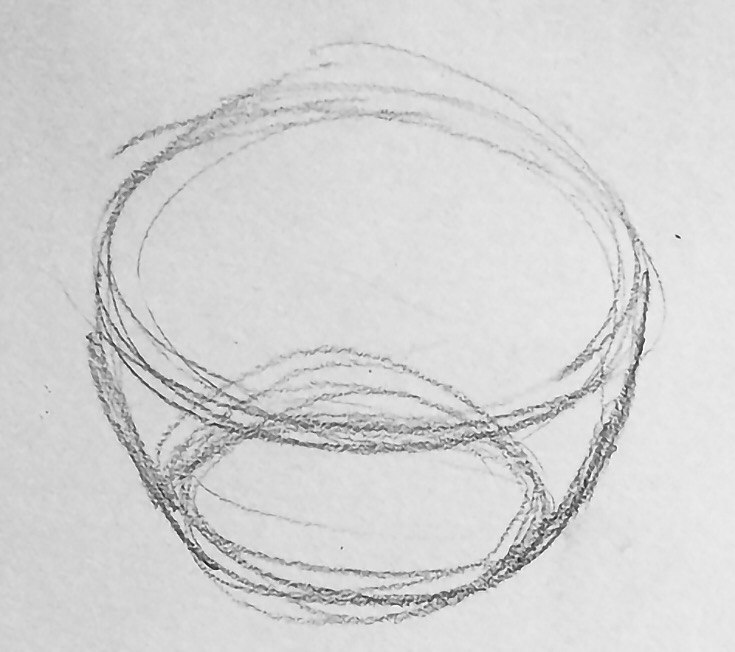

And from this the “idea” of a bowl may eventually result. Furthermore, it would be possible to conceive it and draw it:

Figure 4a

and, eventually, to fabricate a rudimentary model-bowl out of it:

Figure 4b

Lastly, the bowl in question can be handmade and decorated in such or such way, e.g. it can be made out of clay and decorated like this one made by a group of Northwest Coast native Americans, who have added to the bowl proper an upper part in the form of a “hat” or “hut” to cover it, so as to keep the food contained in it either warm or at least protected for a while:

Figure 5

II

The Human Body as a Reversed Pottery Bowl

But why is the bowl decorated in such manner, why does it resemble a human face, with its eyes, its nose, and its mouth? Because, as Lévi-Strauss famously argued in one of his last books(*), just like “nature” and “culture” (or, what Heidegger calls “earth” and “world”) stand in inverse correlation (that is, co-belong each other without forming an empty unity and without merely opposing one another), so too the ingestion of food and the making of pottery (which reflect the “Nature”⎮“Culture” binary) stand in inverse correlation:

A1 The food is contained in the earth

A2 It is cooked

A3 It is digested and thus relaborated by the body

A4 It is ejected from the body as excrement

B1 The clay is extracted from the earth

B2 It is moulded

B3 It is baked

B4 It is turned into a container

A1 is to B4 what A2 is to B3, what A3 is to B2, and what A4 is to B1, and vice versa.

And this means that the pottery bowl and the human body, while standing in inverse correlation to one another, are, nevertheless, structurally equivalent to one another. Thus the human face on the bowl reproduced in Figure 5 above.

III

Nature and Culture

We may assign Figure 1 to “Nature” (henceforth N) and all the other figures instead to “Culture” (henceforth C); in the sense that what figures 2, 3, 4a, 4b, and 5 display entails some degree of (human) conceptualisation (or thought) and elaboration (or handcraft). Thus we have:

N1 (the earth)

C2 (the idea of “curve”)

C3 (the idea of “concavity”)

C4a (the idea of a “bowl” and its projection in a drawing)

C4b (the subsequent fabrication of a “model-bowl” that corresponds to that idea)

C5 (a particular “type” of pottery bowl handmade and decorated by a particular group of people)

We can add to this that C2 and C3 represent a form of “basic conceptual culture” which is common to all humankind. That C4 represents, in turn, a form of “popular conceptual culture” which is likewise universal, as both the idea of a bowl and material bowls of whatever kind can be found across all human cultures. That C5, for its part, represents a form of further-developed “popular culture” specific to a particular human group. And that, in addition to it all, C5 not only further develops and materialises C4 but also illustrates a particular myth relevant for such human group, a myth by which that human group in question represents in a particular manner the aforementioned relation between the human body and a pottery bowl and transmit it thus from one generation to the next as immaterial wisdom; in short, then, a myth that, being intrinsically part of that “people’s culture” reflects, as a myth, what may be called “popular savant culture,” which stands above such people’s “popular material culture” – any of whose bowls may break without the myth thereby being lost: only its preservation will ensure the making of any future bowls. In other words, there is something like C6 (the “myth”) above C5 (which both “materialises” the idea behind C4a and C4b and “reflects” the myth in C6).

Thus we have:

C2, C3 = the BASIC CONCEPTUAL CULTURE common to all humankind

C4a, C4b = the POPULAR CONCEPTUAL & MATERIAL CULTURE developed after the former and common as well to all humankind

C5 = the POPULAR MATERIAL CULTURE particular of a specific human group developed after the former

C6 = the POPULAR SAVANT CULTURE particular of a specific human group

With this we have apparently reached a final distinction, between:

(i) NATURE

(ii) the BASIC CONCEPTUAL CULTURE common to all humankind

(iii) any POPULAR (conceptual & material) CULTURE

(iv) the popular SAVANT CULTURE that constitutes any culture’s wisdom

We ask the reader to keep in mind this division in what follows, including the Latin lower-case numbers assigned to each category.

IV

The Nature⎮Culture Divide in Light of the Difference between Concrete-, Pop-, Classical-, and Serial Music

Today’s music can be classified in four categories:

• Concrete

• Pop

• Classical

• Serial

CONCRETE MUSIC abolishes any distinction between noise and sound. For its proponents, the sound of a car’s horn, of the leaves of a tree when the wind blows or any electroacoustic frequency are as good to make “music” (which is no longer music, therefore) as any note or any interval of musical notes. Concrete music thus helps us to regain attentiveness towards the pluriverse of sounds in which our existence flows, and to experience them more consciously. But if we were to pretend that all music must become concrete, as its supporters claimed in the 1940s, we would have nature without culture or un unworlded earth, i.e. we would remain in region i. Eventually, concrete music can experiment with basic sounds as well, in which case we move from region i to region ii, but do not go beyond that point.

POP MUSIC is like popular culture and extends from folklore to present day pop, rock ’n’ roll, techno, etc. It does something with the basic sounds common to all humanity: it extracts from them musical notes and composes with them simple melodies charged with affective values that make us dream about something, long for something, remember something, feeling emotionally accompanied, etc. It can be better or worse and it of course varies from one culture (national, regional, urban…) to another, even if the quick Anglo-Americanisation that we have undergone over the past sixty years has imposed certain cliches on it to the glory of the capitalist market (strategically designed for the youth in the first place); plus the raise to prominence of suburban pop music and electronics have likewise contributed to standardise it and to turn it into something else instead. In pop music we then witness how the world is rudimentarily extracted from the earth, culture deduced from nature. Rudimentarily and to some degree repetitively, which explains the fact that all popular-music regions would in principle remain enclosed in themselves, i.e. without exploring new sound-possibilities, were it not for the directives of the capitalist market according to which everything must mix to thereby multiply the opportunities of exchange and consumption.

CLASSICAL MUSIC is like the savant culture that constitutes any given culture’s own wisdom: it reworks in more-or-less-complex ways the material produced by pop music, like literature does with the language and the stories distinctive of a specific human group, painting with the chromatic perceptions we are exposed to (which vary from Iceland to Sri Lanka), and philosophy with the notions through which we look at reality and enable ourselves to experience it. Yet at the same time classical music can move downwards to the domain of basic sounds and even below them to the domain of random sounds and think them and explore them afresh to extract from them new musical-possibilities overlooked by popular music, just as it can create other new ones out of its own inventiveness. In a word, its spectrum is broader in comparison to both concrete and pop music. We are willing to define classical music, therefore, as a fully worlded earth, or as a better-achieved equilibrium between nature and culture.

SERIAL MUSIC (and its variants) is instead like a world without earth, or like culture without nature. Music remains music, i.e. something more than sound, but it loses its link to popular music and it is no longer classical music either. It becomes a purely intellectual game: a mathematical game, more or less mathematical (like Boulez’s) or more or less playful (like Cage’s, whose music, therefore, is no longer serial but its very reverse: indeterminate by being open to chance). If concrete music is like putting toothpaste in between two lines of Chinese literature written in Braille, and pop music like a couplet, and classical music like a novel by Balzac or a poem by Trakl, serial music is rather like a 375-line poem (plus an optative additional verse) made with all the letters of the Latin alphabet but without forming with them a single meaningful word.

(*) Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Jealous Potter (translated by Bénédicte Chorier; Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1988).

John Cage, score for Fontana Mix (1958), excerpt