(A sequel to “Phantasmagoria“)

There are two different theories of dreaming. One interprets dreams according to well-established a priori categories (such as complexes) and views dreams as symptoms of the dreamer’s personal expectations and frustrations, family and social roles, etc. Conversely, the other one approaches dreams in pragmatic and heuristic manner (as in a trial-and-error procedure lacking predetermined rules) and takes them to potentially help the dreamer explore new worlds of possibles which need not be person-centred (after all, one can dream of becoming the wind that ripples through a wheat field, just as one can dream with Sashiko geometrical patters or with the theriomorphic powers of an Amazonian shaman).

The roots of the former theory can be traced back to the various forms of typological interpretation of the Bible peculiar to late-antique and medieval Christianity, though it was Freudian psychoanalysis that first projected a typological grid onto the doings of the unconscious.[1] In turn, a pragmatic approach to these (dreams included) is characteristic of Guattarian schizoanalysis[2] and echoes extra-modern approaches to dreaming.

The Ngaing living in the Finisterre Range of Papua New Guinea think for instance (I have chosen the verb very carefully; see further my discussion of the common misinterpretation of indigenous thoughts as believes) that it is not oneself who dreams, but one’s double or asabeiyang (“shadow,” “ghost,” “spirit”).[3] But to understand what this actually means it will be necessary to take a little detour.

Let’s begin by looking at the constitutive parts of the extra-modern body. The latter usually divides into a tribal body and a shamanic body; and the tribal body subdivides, in turn, into a totemic body and a family body. Hence, it is safe to deduce that an extra-modern body is best though of as collection of different bodies, or, more exactly, that what we call a body denotes a relation of unstable equilibrium between distinct bodies.

The family body links the “person” (in lack of a better term)[4] to its group (family, clan or tribe); in fact, in many indigenous languages the expression “my body” refers to that extensive body. For its part, the totemic body links the person to the group’s totem (“I am a toucan”).[5] And then there is the person’s shamanic body which is capable of undergoing transformations or becomings (“I have become a jaguar”).

In this respect, the extra-modern body resembles the archaic Greek body, which is kept together by virtue of its parts’ shared memory and friendly disposition towards each other[6] butpresents no other form of unity, for which reason any of its parts can be individually possessed by gods and daimons. Besides, these two types of bodies differ from the Christian and modern body, which is enclosed within the organism and subjected to the person’s soul or self, thus forming a self-contained totality governed by an indivisible and likewise self-contained entity (“me”).

What about the self, which in Western culture(s) is commonly taken to be the dreaming subject? Is there an extra-modern term for such notion? Not really. In archaic Greece, the word ψυχή (psyche) refers to what one can become through life (notice its performative character) and/or to the lifeless shadow that leaves the corpse when one dies (notice this time its unessential overtones). In short, it denotes both a figure (a mask) and a ghost. There are several extra-modern words for it, as well. We have written elsewhere on the role attributed to the ghosts of the deceased in most indigenous worlds, where a dead person usually becomes a ghost (that is to say, a floating figure or image) before becoming an ancestor. Yet, one’s ghost (asabeiyang in the Ngaing language) is also one’s double in life.

Let’s be clear: that double is not oneself, for one’s self (“who are you?”) is made (a) of several overlapping kin relations (“son of…,” “husband of…,” “father of…”) and (b) of certain rather conspicuous physical traits epitomized in one’s given nickname. No indigenous person will ever respond to questions about their identity but mentioning either their nickname or their relational names. One’s double is, therefore, one’s other. And yet, that other is paradoxically more central to oneself that one’s own self is. Why? Because it does not name what one is, but the secret power that enables one to become more than one is. Accordingly, it is designated by one’s proper name, which must never be pronounced, or be pronounced only exceptionally, to avoid making it fall where it does not belong: on the side of the world as it is and we know it. For it belongs in that other part of the world which is not yet (and no longer).

Ultimately, at stake in all this is the DIFFERENCE between the REAL and the POSSIBLE, which, to keep things simple, stand in opposition to each other, in the sense that the possible is the reverse, i.e., the shadow of the given, and vice versa.

In philosophical terms, real and possible are catalogued as two modal categories, as they denote two specific modalities of being, or how things can be (real or possible).

Thus, asabeiyang (or any other similar term, e.g., ψυχή according to its original meaning) is not an object of belief (which is what one would wrongly assumes if one were to state: “the Ngaing believe we all have a double”). It is a concept: the very concept of the possible as opposed to the real, but it is a concept turned sensible, hence a sensible concept, like the concept of baiya among the Atchei of the Paraguayan Chaco, which serves them to thematize the modal difference between the living and the dead. It is a sensible concept because… you can indeed see someone’s asabeiyang. But again, there is nothing irrational in this either, as we shall immediately see.

Let me add first, though, that there is not only a sensible surplus to what we would label merely as a concept (as a pure concept turned sensible and thus somewhat impure): there is also some delight put by the Ngaing in the twisting nature of the bi-dimensional opposition whose knot such concept reveals.[7] This makes of the concept of asabeiyang not only a sensible concept, but a humorous concept, as well.

We have already quoted it elsewhere, but I cannot resist reproducing it here again – for the sake of the passage’s humorous nature and because it goes straight to the point; I add a few comments in square brackets:

Roy: “One evening in 2000 I was walking across the Karimui air-strip [in the Highlands region of Papua New Guinea] – the only really cleared area in the region – with some young Daribi kids. The kids were dumbfounded by their long shadows projected across the field by the setting sun. ‘Wow,’ they said, ‘SOULS!’ and then they giggled.”

[That is to say, they identified their shadows with their doubles… or souls.]

Coyote [mocking the way in which the kids downplayed what is elsewhere seen as a crucial metaphysical issue, namely, the existence or not of the soul]: “That, too, is a funny way to put your whole existence.”

Roy: “Next day I took the matter up with my friend Danu, the magistrate: ‘Why is it that you people identify the animating principle, that thing you call the bidinoma, with the shadow, or name, or photograph of a person?’”

Coyote: “And he gave you the Daribi blessing, didn’t he: po mene, ‘no talk,’ an expression of extreme satisfaction or annoyance.”

[Like saying: you’ve got it, the bidinoma (the Daribi noun for the double) is also the shadow. But c’mon, can’t you guess yourself why?!]

Roy: “As a matter of fact he did not. He simply said ‘I’ll show you. Stand over there, Roy, and stare at your black shadow on the ground. When you are finished, look up at the blue sky and tell me what you see.’ I did as I was told, and when I looked up at the sky I saw a visual effect, a rods-and-cones afterimage of the dark silhouette I had just been staring at – a glowing, luminous shape of my body floating in the blue.”

Coyote: “And you said something like ‘That’s it?’ or ‘That’s all?’”

Roy: “Something like that. And he said, ‘Well, it ANIMATED you, didn’t it?’”

[It entertained (animated) you to realize we envisage the soul (anima) in this way, didn’t it? (He laughs.) And to think we have been despised as animists, we have been told we irrationally projecting animating principles onto things inanimate… They’ve never understood our sense of humour!]

Coyote [focusing now on the enigma implied in the episode and creating new playful concepts to delimit it in a sort of dice throw]: “So was it your impersonation looking at your expersonation, or your expersonation looking at your impersonation?”

Roy: “That’s IT, Coyote, you got it in one. [For who’s who depends on the perspective taken! (Joking:)] Next time try flipping a coin with only one side.”[8]

After all, humour is – what else?! – the art of flipping reality’s (always-already) two-faced coin (for reality is always composed of this and that, now and then… and their many interstitial nuances) and to make you flip thus.

Plus, look around and you will see that the concern with the asabeiyang (whatever the name given to it) is, how to put it, pervasive – again, inasmuch as it amounts to the concern with a particular form of reality’s ever-twisting bi-dimensionality: real or possible? Or do we all not take shelter in the fact that the possible always points beyond the given? Does this not inspire us and keep us dreaming?[9]

By way of example:

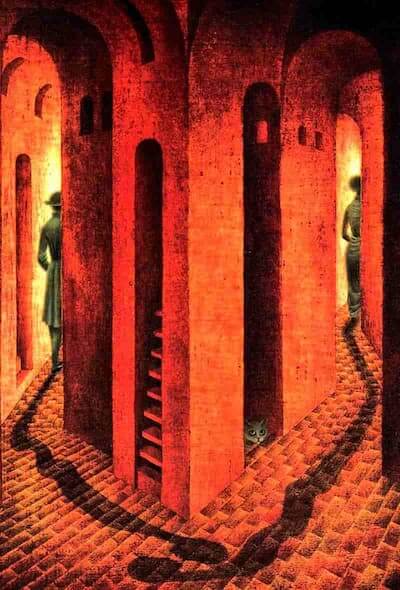

Remedios Varo, Farewell (1958)

(There is little mystery in that a cat witnesses the event dreamt by the farewelling couple, the encounter that would counter their farewell; for cats too belong, as we all know, in reality’s other side.)

Still not persuaded? Once more, just look around:

Giorgio de Chirico, Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (1914) • Remedios Varo, A Phenomenon (1962) • Peter Pan, Walt Disney Productions & RKO Radio Pictures (1953) • Morris (Maurice de Bevere), Lucky Luke, a.k.a. The Man That Shoots Faster Than His Shadow (1946).

The shadows in these images hint variously at that which is not or cannot be contained within the given. Consequently, they have acquired autonomous life – a life that, for better or worse, transcends the unambiguity of what is; hence its oddness.

For better or worse? Obviously. De Chirico’s Mystery and Melancholy of a Street proves particularly insightful in this regard, as it opposes a nonchalant shadow (the girl’s, who comes out of the luminous left side of the painting playing hoop rolling) to a disquieting or menacing shadow (the man’s or the statue’s belonging in the shadowy right side of the painting). For both what we fear to come and what we hope for to arrive – the possible’s two sides, that is: one positive, the other one negative – lies in shadows.

Variant: the possible is the field of our dreams and nightmares alike.

F. W. Murnau, Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) • Bob Kane, Batman (1939)

And so the Ngaing say: IT’S YOUR ASABEIYANG WHO DREAMS, NOT YOU.

Now, this equals to say that DREAMS DISPLAY AN ELICITING FORCE[10] CAPABLE OF DANCING THROUGH, BENEATH, ABOVE, BEHIND, AND IN BETWEEN THE DISCRETE FIGURES THAT CONFORM REALITY AS SOMETHING GIVEN.

Roy Wagner distinguishes in this respect a “first” and a “second attention.”With the “first attention,” he says, we “pick out” the forms and “figures” (people, places, things) that make the world as we know it; by contrast, with the “second attention” we “feel” their “background.”[11] “Second-attention,” Wagner adds, “is our ‘dream’ of the world and our bodies use this feeling of the world to move with.”[12] Yet this means that DREAMSCAPES AND DANCESCAPES SHARE A COMMON ONTOLOGICAL PLANE: THAT OF THE OTHERWISE – which is also the plane where the shamanic body and the shadow or ghost or double exchange with one another and become iridescent.

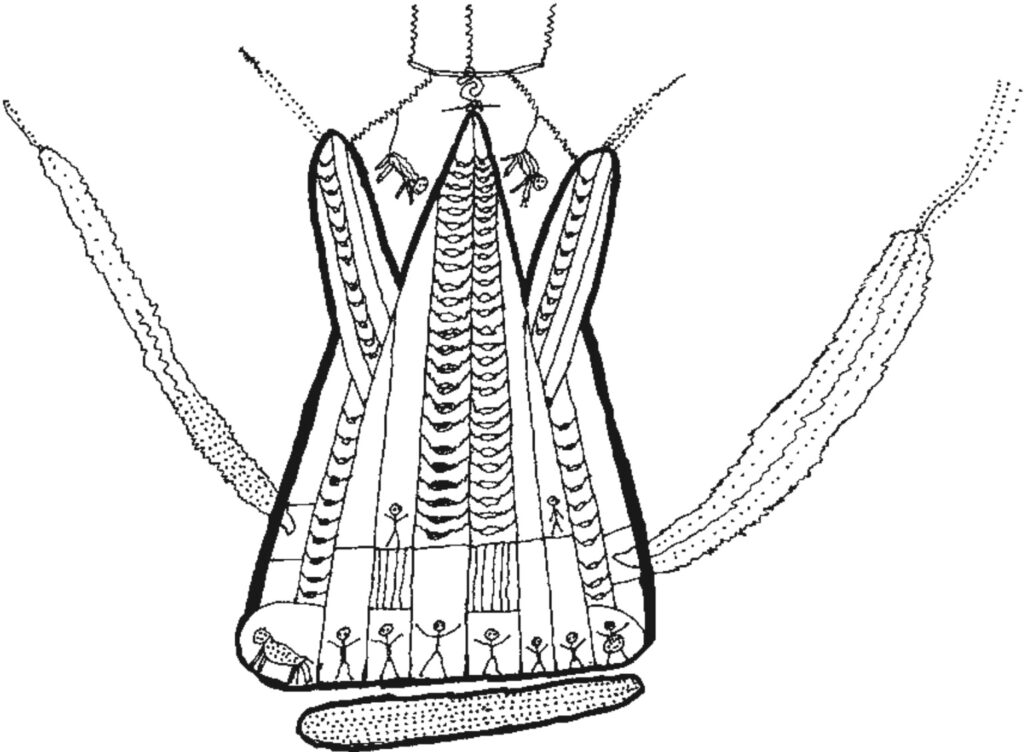

“If you want to move like an old man, don’t imitate an old man, but try to feel how the old man tries to move as though he were still young but can’t,” reds al old Nō theatre maxim. Mardu Aborigines, writes Robert Tonkinson, “do not merely imitate or emulate the movements of the […] being depicted [in their dances], but […] leave their [own] state and temporarily become one with that being.”[13] Sofya would surely say such is also the premise of Butō dance, which can lead the dancer – like dreams can lead the dreamer – to become not just other beings, but also other phenomena (air, water), if such distinction makes any sense, as well as things more difficultly classifiable (a presence? an affect?), or else never seen before. Dreams, too, are made of this, as Davi Kopenawa’s xapiri houses remind us – the xapiri being the images of the forest spirits, which consist in dancing.

Dreamt xapiri house with hammocks, paths and mirrors, where forest spirits arrive dancing – Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert, The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman (Cambridge, Mass., and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013), p. 97

In short, ONE ALWAYS DANCES A DREAM, AND ONE’S DREAM IS ALWAYS A DANCE. For when one dances, like when one dreams, one oversteps the boundaries of that which is clear-cut or present: one moves, that is, as one would not normally move, just like one sees in a dream what one would not normally see.

Butō dance, for its part, brings those waters together in an incomparably powerful way. In my view, Butō dance draws from, and merges, four sources – other, that is, than Nō theatre, where, in addition to what I have already mentioned concerning bodily metamorphosis, a waki (“human person”) meets, and is spiritually turned inside out, by a shite (or other-than-human “spirit”). These sources are: (1) Tatsumi Hijikata’s exploration of the phenomenon of bodily possession; (2) Kazuo Onō’s parallel exploration of the possibilities of bodily metamorphosis; (3) Ono’s use of mime; and (4) Hijikata’s flirt with the surreal and the grotesque. They all point to the Otherwise, albeit differently. (I am personally more interested in 1 and 2than in 3, and in 1, 2, and 3 more than in 4, which has become today the most widespread approach to Butō, perhaps because it is the easiest one; but, again, they all point to the Otherwise.) Mainstream contemporary dance does not, however, for it is mainly about moving (oneself) through space and time. “What do dancers do? They move. […] Where does the dancer move? Through space […] in relation to time? How? […] [W]ith energy!” These are dance’s basics at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (N.Y.), whose educational program thereby puts the stress on the human body qua human body: “The human body is what others see when they look at dance. Sometimes the body is still; other times, it may be in motion. A dancer can use the whole body, or emphasize individual body parts, when moving.” In contrast, Sondra Fraleigh refers to Butō dance in these terms: “since we cannot live in a perpetual mystery, we invented dancing to give the shadows its visible form.”[14]

c.

Sofya dancing (April 2023 • May 2024)

Notes

[1] A. Schuster speaks of two “halves” that do not quite make a “whole” in Freud’s theoretical edifice: on the one hand, he says, we have Freud’s symbolicpicturing of the unconscious in his trilogy works: The Interpretation of Dreams, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, and Psychopathology of Everyday Life; on the other hand, there is Freud’s theory of drives in his Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality and later essays on metapsychology, where “the psyche is presented in quasi-machinic terms, as an apparatus for managing the stimuli that affect it from both without and within” (Aaron Schuster, The Trouble with Pleasure: Deleuze and Psychoanalysis [Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 2016], p. 47).

[2] Jungian psychoanalysis stands in between both, as it aims to enable the dreamer to interpret their dreams in creative terms but in accordance with a series of predetermined archetypes.

[3] See Wolfgang Kempf and Elfriede Hermann, “Dreamscapes: Transcending the Local in Initiation Rites among the Ngaing of Papua New Guinea,” in Dream Travelers: Sleep Experiences and Culture in the Western Pacific, ed. Roger Ivar Lohmann (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), pp. 61–85.

[4] McKim Marriott coined long ago the term “dividual,” which Marilyn Strathern has later reused. See Antje Linkenbach and Martin Mulsow, “The Dividual Self,” in Religious Individualisation: Historical Dimensions and Comparative Perspectives, ed. Martin Fuchs, Antje Linkenbach, Martin Mulsow, Bernd-Christian Otto, Rahul Bjørn Parson, and Jörg Rüpke (Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, 2020), pp. 323–43.

[5] On the meaning of this and other similar sentences, see here.

[6] Why else would I always open the toothpaste tube with my left hand, a gesture which my right hand seems to be incapable of?

[7] Knots of this type are philosophy’s original battlefield – suffice it to read Heraclitus. The reason for it is simple: philosophy is – as Giorgio Colli has pertinently showed – the continuation, by other means, of the twisting logic of enigma that so much fascinated the ancient Greeks (who moreover were sailors familiar with knots).

[8] Roy Wagner, Coyote Anthropology (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), pp. 49–50. Naturally, photographs are equated, too, with people’s doubles. For what you see in a photograph is someone an image that resembles someone, but precisely then what you see is an image; hence not the person, but the person’s image, i.e., the person’s double. After all, I can say: “It is not me who is in that photograph, for look, touch me, I’m here.” But this means it is the other (“my other, my ghost!”) who is imprisoned in the photograph – and the same applies to mirrors. The Ache “had never seen mirrors before and immediately called them chaa, eyes, just as they called my glasses chaa beta, tembeta, eyes,” tells Pierre Clastres. “They were not merely surprised when, like Plato’s prisoner leaving the cave and looking at his reflection in the water, they saw their faces in the chaa for the first time: it would be more accurate to say that they were spellbound. For half an hour at a time, even for an hour, they would look at themselves (especially the men), sometimes holding the mirror at arm’s length, sometimes right under their noses, dumb with astonishment to see this face, which belonged to them but which they could not feel: when they tried to touch it with their fingertips, they felt only the cold, hard surface of the chaa. Sometimes they turned the mirror around to see what was behind it. The Atchei were very excited about the chaa, and they all wanted to own one. This passion even provoked behavior that was rare among Indians: the desire to hoard. Several women actually accumulated as many as five or six mirrors, which they stuffed in their baskets and brought out from time to time to examine” (Pierre Clastres, Chronicle of the Guayaki Indians [trans. Paul Auster; New York: Zone Books, 1998], p. 93).

[9] And living. Pasolini claimed that a person’s life acquires full meaning only when they die; for, until that moment, everything is possible.

[10] We have written on its manifestations here.

[11] Roy Wagner, Coyote Anthropology (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), p. 14.

[12] Ibid. Needless to say, while these two attentions oppose one another, they also change into one another, so that “[c]aught in a play of light and shadow between one extreme and the other” (ibid., p. x) our perception of reality oscillates between two dimensions which shift into each other in a permanent “figure-ground reversal” (ibid., p. 14) like – we have dedicated them a book because of it – Dionysus and Apollo.

[13] Robert Tomkinson, “Ambrymese Dreams and the Mardu Dreaming,” in Dream Travelers: Sleep Experiences and Culture in the Western Pacific, ed. Roger Ivar Lohmann, pp. 87–105.

[14] Sondra Horton Fraleigh, Dance and the Lived Body: A Descriptive Aesthetics (Pittsburgh, PN: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1987), p. 31. In rigour, she wrote this (back in 1987) about dance in general, yet shortly afterwards she entered the Butō world, on which she has written uninterruptedly ever since.