Perfect is an adjective meaning thoroughly done (Latin per-fectus) and thereby done with care and eventually too, then, completed or free of fault.

If, as a general rule, what is beautiful is that which is perfect, then neither everyone nor everything can be equally beautiful.

Conversely, if, as a general rule, what is beautiful is that which is imperfect, then everyone and everything is equally beautiful.

The former argument is qualitative – it points to difference in quality as the criterium capable of determining what is beautiful and what is not. In contrast, the latter argument is political – it aims at the democratic levelling of what would otherwise remain exclusive of a few.

As per this latter argument, then, a failed poem is deemed equal, say, to the Iliad (on which I have briefly written here); and the random recording of a burp, equal to that of Glenn Gould’s interpretation of Mozart.

But how is it that this argument has made it through, one might ask? Very simple.

(1) On the one hand, it unconsciously prolongues the very-widespread Christian view that we are all sinners, hence imperfect, and thus equal on the lowest possible basis; and that whoever objects to this must be seen as arrogant.

(2) On the other hand, it reflects a willingness to reverse the normative logic that has it that what we experience is good if it fits certain standards and bad if it does not, by claiming instead that whatever does not fit the norm is good and whatever fits it is bad.

As any reactive view, 2 has nothing to offer but in negative terms(*). As for 1, it only makes sense as a Christian premise – one that need not be necessarily assumed, therefore.

I feel it is an altogether different kind of logic we must look for. One based neither on miserabilism nor on despotism and its reversal, but on the value of what we do, which needless to say varies from one culture to another and from one domain to another, but is always related to the notion of everything being thoroughly and carefully done.

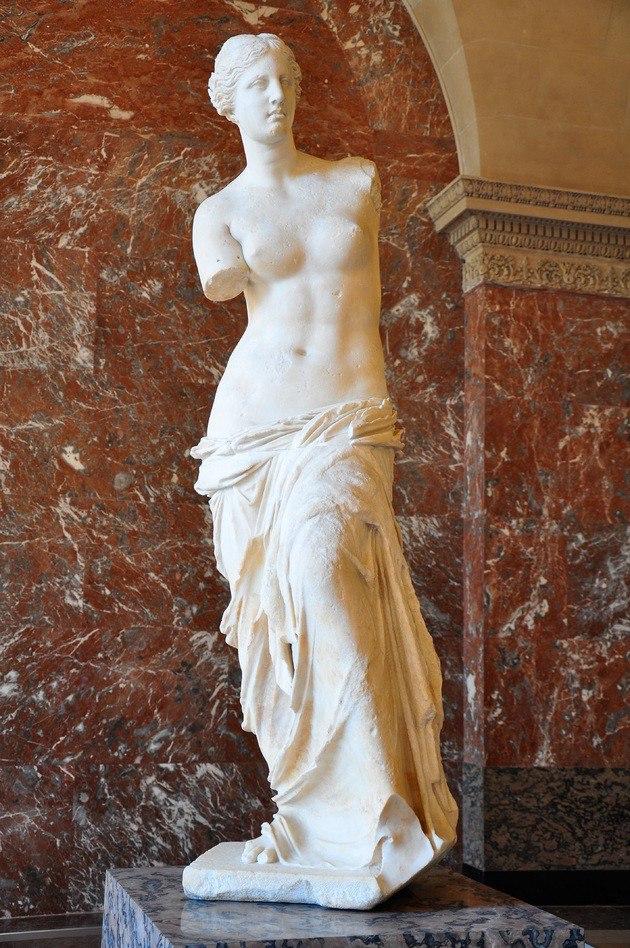

But is it not that the supposedly imperfect can eventually prove beautiful, as well? Of course. For example, it does so whenever it carries with it the trace of life and death having crushed at some point, like in the image below or in the case of a one-eyed kitten. Dissymmetry, too, can prove beautiful, when they supplement with an enriching difference what would otherwise remain too expectable and homogeneous, thus echoing life’s tendency to variation; for instance, a counter-rhythm in a musical composition or a chromatic dissonance in a painting may offer more rather than less.

As suggested above, different cultures have heterogeneous views on what is perfect. However, if, for example, a Western anthropologist deciphers the meaning behind a distorted extramodern ritual mask, she may see it beautiful, that is to say, embodying the perfection of what a ritual mask must be in that context. In the same way, butō dance is usually seen as ugly and disturbing by unfamiliar viewers, although viewers familiar with it may find it beautiful and impressive due to the fact that they understand the ideas that stand behind it and see the dancers’ body traversed by forces, spirits, ancestors or gods – in short, traversed by life.

Understanding, therefore, plays a crucial role in recognising and determining what is beautiful.

In turn, those imperfections that cannot be said to be beautiful – those imperfections that truly deserve the name of imperfections – are those derived of any sort of duplicity and vileness. For example, an abusive boyfriend or husband who justifies himself adducing that he does not know how to love and that imperfection is human after all.

Interestingly, ancients as much as indigenous peoples have generally endorsed ideals of excellence: the sage old man or woman, the best warrior… They understood that we are seldom equal in terms of what we are good in and what we achieve, although we all must be given the same conditions to achieve the best, one must surely add.

Pursuing excellence gives us wings to fly, hence to live thoroughly and intensely and caring for everything by impeding it to fall into darkness and oblivion (on which see more here). And that is why it is beautiful.

One should be careful, then, with making out of perfection and beauty a norm. This often leads to arguments such as “perfection is unreachable, and gives rise to judgement,” and “there is no single standard of beauty.” Doing things well and beautifully has nothing to do with norms, and aspiring to it can only be praised. Moreover, what would any social world be without any ideals of beauty and perfection? Turning perfection and beauty into a question of normative judgment is a mistake, as there are different, indeed infinite, ways of making things perfectly and beautifully, that is, thoroughly and with care. We can all find ours(**).

(*) It is, furthermore, an unjustifiable view, as fighting against something can never be justified in negative terms alone. Subversion is our right, yet its goal cannot be to destruct but to make possible something better than what must be wiped off, and therefore cannot dispense with ideals. Nihilism is always a mistake, even when it is reactive (when in order to fight against certain values one denies the existence of any values) instead of being merely passive (which amounts to the frustrated denial of any values).

(**) One could perhaps rethink in this context Schiller’s idea of beauty as auto-poetic and self-creative, and therefore in connection to freedom. Nature’s autopoiesis is a great example of this.

The Venus de Milo (late 2nd-century BCE) at the Louvre Museum in Paris combines two different types of beauty: formal perfection and the imperfection derived from the passing of time, which makes it a living witness to the dialectics of life and death (the long-lived vs. the short-lived).