In the first place, difference presents itself in two ways: as difference in nature (a dolphin is different from a violin because their respective natures differ) and difference in degree or gradual difference (it is now warmer than it was earlier this morning).

Yet difference can be also thought in terms of archetypes and their mimeographs: she is a good mother, but he is not such a good brother. In this case, an ideal reference is required: a norm against which things may be compared. But then, says Deleuze, identity is privileged over difference, in the sense that iconic reflection, and thus the repetition of the identical, is taken to be difference’s rule. We are here before an extension of what we have called the principle gradual difference: depending on their degree of approximation to, or deviation from, their originals, things are identified as their good or their bad copies; or, what amounts to the same, as their true “copies” and their “false pretenders,” as their authentic mimeographs and their “simulacra.”(⦼) Not only does multiplicity fall into the trap of unity under this all-too-symmetric(⧀) logic of “resemblance,”(⧁) adds Deleuze: ontology, too, falls into the trap of morality, insofar as what is is judged after, and thereby replaced by, what should be. What would happen if such logic were “reversed?” Is it possible, asks Deleuze, to “make the simulacra […] rise and […] affirm their rights among icons and copies?”(⊕) Would this not amount, as Nietzsche intended, to proclaim “subversively”(⊗) the “twilight of [all] idols”(⊛), to vindicate “difference in itself”(⦿) so as to establish “the Different as primary power?”(⦶) Very likely, but the result would be a reality made up of infinite and unrelated singularities: a totally contingent world through which one would only be able to move pointing at things that would ultimately refuse identification, as for things to be identified they must be somehow classified, and it is not possible to classify them at the expense of universals, no matter how nuanced we may fancy them. In short, this (x) would be irreducibly “this,” that (y) would be irreducibly “that,” and so on and so forth: deictics would substitute for concepts. Arguably, we are here, in turn, before an extension – in rigour, before a distortion – of what we have called the principle of difference in nature. Actually, it can be said that Deleuze’s philosophy, notwithstanding its apparent novelty, consists, first, in erasing the notion of gradual difference, and, secondly, in making of any possible difference in degree a difference in nature; which means that, despite all, Deleuze does not move beyond an otherwise classic conceptual dichotomy: he merely privileges one of its two constitutive options, discarding the other one.

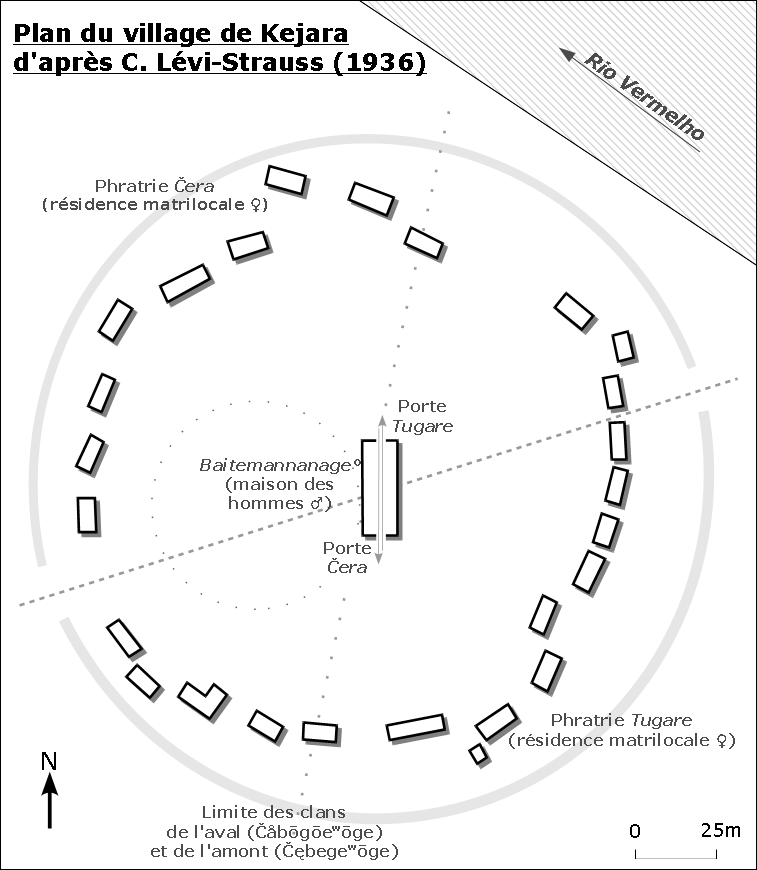

Against this, structuralism offers an approach to difference that affirms difference in its irreducibility, or as that which is: “resemblance has no reality in itself,” writes Lévi-Strauss, “it is only a particular instance of difference […] in which difference tends toward zero.”(⊙) Nonetheless, structuralism posits difference as reciprocity – that is, as bidirectional relationality and as coupled identity – in a number of cases (e.g. kinship, myth, and ritual) which are particular relevant for the study of human sociality.(⦷) Consider, for example, the relationship that exists between the two moieties (or clans) of a tribe, which oppose but at the same time depend on one another in terms of consanguinity and affinity.

“The Bororo shaman,” writes Lévi-Strauss, “offers food to the evil spirits on behalf of the spirit’s son, if the food was brought by a member of the Tugare moiety; and on behalf of the spirit’s son-in-law (or grandson), if the food was brought by a member of the Čera moiety. […] However, the Čera are treated as sons by the shamans and the Tugare as sons-in-law. Thus the shamans stand in the relation opposite to the members of both moieties to that of the spirits”(⊜)

| from the spirits’s viewpoint | from the shamans’ viewpoint | |

| Tugare | sons | sons-in-law |

| Čera | sons-in-law | sons |

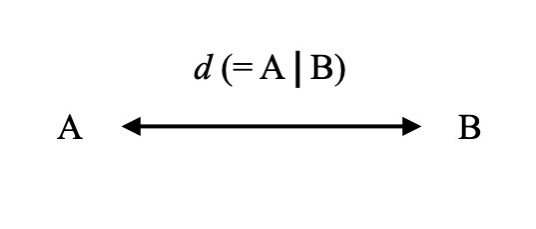

In this case, therefore, difference is best defined as complementary opposition, and hence in structural terms: given two elements, A and B, they can be said to form a “structure” when and only when A proves to be, and to be what it is, inasmuch as it differs from B, and vice versa, their co-implied difference (d and⎮in the formula below these lines) being the meaningful relation that determines their individual qua joint being:

Plus, in addition to thinking difference as reciprocity, structuralism makes of variation another fundamental class of difference. We have written on it here.

Needless to say, difference (in nature) can also be thought in terms of ontological difference: I see myself in a way that differs from the way in which a jaguar sees me. Multinaturalism is at play here: reality is inherently manifold. Cross-cultural variation of the same principle: a Darkhad shamanic gown may look to you a piece of cloth; the Darkhad view it very differently, though: they see it as a device capable of bringing together space, time, communal life, and individual life, as the gown it is made of vegetal and animal tissue, bears on it the chronological marks of the ceremonies in which it has been used, and it is used to heal particular individuals belonging in a specific social group. More on cross-cultural ontological differences here and here.

Lastly, difference and identity can display chiasmatic relations: one may want to be very different from someone else (think, for instance, of a son who does not want to resemble his father) and yet unconsciously behave like that someone; and the other way round: things might seem similar at first sight, and then appear to be entirely dissimilar.

(⦼) Gilles Deleuze, The Logic of Sense (trans. Mark Lester & Charles Stivale; London: The Athlone Press, 1990), p. 253-262.

(⧀) Cf. the critique of symmetry in Deleuze, Difference and Repetition (trans. Paul Patton; London and New York: The Athlone Press and Columbia University Press, 1994), p. 20.

(⧁) Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, p. 257-262.

(⊕) Ibid., p. 262.

(⊗) “There is no sin other than raising the ground and dissolving the form” (Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 29).

(⊛) Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, p. 262.

(⦿) Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, p. 28-69.

(⦶) Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, p. 262. Cf. Difference and Repetition, p. 30: “is difference really an evil in itself? Must the question […] [be] posed in these moral terms?; p. 29: “To rescue difference from its maledictory state seems, therefore, to be the project of the philosophy of difference.”

(⊙) Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Naked Man (trans. John & Doreen Weightman; New York, San Francisco, and London: Harper & Row, 1981), p. 38.

(⦷) Cf. Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis, A Cooperative Species: Human Reciprocity and Its Evolution (Prince Princeton & London: Princeton University Press, 2013.

(⊜) Claude Lévi-Strauss, “Reciprocity and Hierarchy” (American Anthropologist 46 [1944]: 266-268), 266.

Lévi-Strauss’s plan of a Bororo village, with the areas corresponding to the two moieties (the Čera above and the Tugare below) demarcated by a dotted line. Notice that this division is reversed in the case of the main building located at the centre of the village, whose Tugare door opens to the area inhabited by the Čera, while its Čera door opens to the area inhabited by the Tugare. We have written on this “dynamic disequilibrium,” as Lévi-Strauss himself calls it, here, a propos the Mekeo of Papua New Guinea.