It is with Heraclitus that the “thinkable” becomes the very object of thought – and I am tempted to

assert that it is only then that philosophy properly begins. The apocryphal anecdote concerning the death of Homer contained in frag. DK B56 (to which I have already alluded here) hints at this in a lovely manner which tells us about humour’s ability to bring out meaning by piercing it, as Roy Wagner puts it. The poet meets a group of young fishermen returning from the sea and asks them: “Did you catch many?” They reply: “Those we caught, we left; those we did not catch, came with us.” Unable to decipher this enigma – because he has fish in mind, while the young fishermen have

lice – Homer dies.

Thus, the meaning implicit in each case, what transforms the saying into something thinkable like A or B – fish or lice – shifts from one context to another. And this is also the idea underlying Heraclitus’ λόγος [logos, “gathering”], which is at the same time there and not there (cf. frags. DK B41, B91 and B108).

Now, let’s take the simplest possible types of enunciation that anyone can formulate:

“A is B” (which says or predicates something: B about something else: A;

or which, seen in reverse, allows A to manifest itself as B)

“A and B” (which consists of two terms added together: A, B)

“A or B” (which, of two terms, keeps only one: A or B)

“A” (consisting of a single term: A)

In the first case, two things are brought together by attributing something (say, a quality, say, “brave”) to something or someone else (say, “Achilles”). In the second case, two things are brought together by adding them to each other (because they share the same chromatic properties, like two green leaves; or because they are of the same type, like two pairs of shoes; or because they belong to the same city even though they are from different eras, like the Milan Cathedral and the Torre Velasca, etc.). In the third case, two things are brought together by differentiating them (as in Heraclitus’ fragments and Rothko’s paintings, about which I will say more later). But what about the fourth and final case? Here too, something is brought together, now as A, against a background of indeterminacy where there is not yet A, nor B, nor C, or where, at the very least, A cannot be distinguished from other things even though these might be distinguished in turn. Hence, in the four cases a certain λέγειν [legein, “gathering” this time as a verb rather than a noun] occurs; and that λέγειν poses itself as thought’s simplest and most primordial gesture.

Accordingly, if we say “A is B,” if we say “A and B,” if we say “A or B,” and even if we merely say “A,” this means tracing at the same time, even if provisionally, a certain identity and a certain difference: either of A in relation to B (as two distinct but related things, grouped in the same whole or reunited by their dissociation, respectively) or of A in relation to all other things or to what I have called an indeterminate background. And, as I have argued elsewhere, this is why Plato, in his unwritten doctrines, places two ἀρχαί or “principles” (namely, “One” and “Non-One”) above all other ideas (the only exception being the very idea of the “space of meaning” where all ideas must be placed in order not to be devoid of sense).

Let me repeat it then: thought’s fundamental axioms are Two because, as Plato says in the Parmenides, we cannot begin to think what is, that is to say, we cannot begin to think “being,” from the idea of the “One”; if we did, how could we avoid asking ourselves questions such as: is the “One” different from the “non-One”? or what is the difference between the “One” that we say “is” and the “being” of this “One”? In the same way, we cannot begin to think of being from the idea of the “Many,” because then how could we avoid asking questions such as: is the “Many” different from the “not-Many”? or what is the difference between “Multiplicity” and “Totality”? Furthermore, one might ask – this is the idea implicit in the Meno – whether a multiplicity without an idea that unifies and delimits it can truly designate something.

It is therefore only with the “Two” that one can begin to think of what is. And since what may appear as “One” can reveal itself as “Not-One” from another angle and vice versa (A and B can be together and not together depending on the subject matter), this is why Plato suggests in the Sophist – though little if any attention has been paid to it – that “being” is a mixture of “being” and “not being”, of “same” and “other”, of “rest” and “movement”. But then, how can we bring to a halt, if provisionally, the instability of reality, which Plato admitted in the Theaetetus, otherwise than through an activity of permanent (re-)conceptualization?

This is what we find in Plato if we remove from Plato the banalization of his thought, a.k.a. Platonism – the very same Platonism that Deleuze (but he is not the only one!) repeatedly confuses with Plato himself (as I have underlined here): a thought that affirms sensible both fluctuation and ontological instability (and thereby, as can be deduced from the Phaedo, exactitude and conceptual relativity at once) and, consequently, a thought that discards the One and the Many as valid starting points and replaces them with two ἀρχαί which are in chiastic relation to each other.

But all this, which should serve to demonstrate Plato’s systematically overlooked fidelity to Heraclitus, is – let me add it quickly – what we also find, for instance, in Guattari, and very especially in his latest works, where quadripartitions of all kinds (ontological, modal, temporal, processual, psychoanalytic, mythological…) complicate structures that are essentially dual and chiastic (as dual and chiastic were the early categories he was working with before encountering Deleuze, for example those of intensity and figure, “power-signs” and “figure-signs”). Briefly: in the later Guattari Four appears for what it is: a multiple of Two.

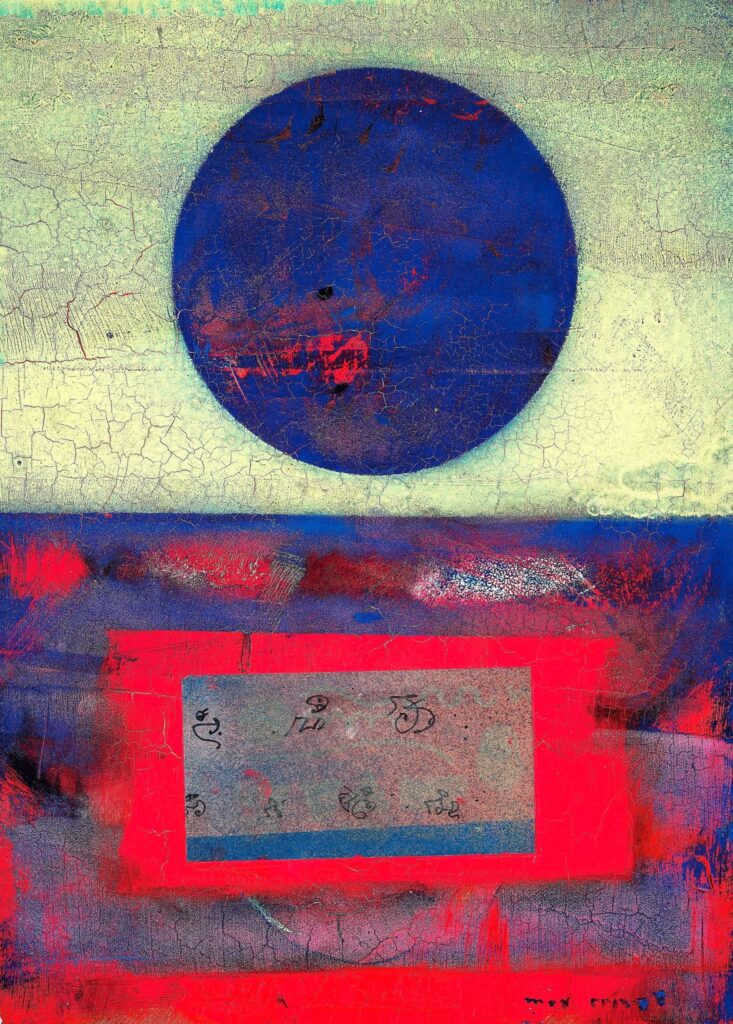

Max Ernst. Ohne Titel (1962)