It is possible to distinguish among two major linguistic functions: one denotative, the other one poetic. We have already touched upon the latter when talking about gods, heroes, and mortal things. The denotative is likewise essential to any living, as by naming things we manage to identify them. And this, moreover, is the basis on which the poetic function stands in turn: you can only sing to what there is in the world by first identifying it. Nonetheless, if used alone – that is to say, if used at the expense of the poetic – the denotative function presents its risks. For by naming things without singing to them we tend to capture them and use them for our own ends (“this is a ‘tree’ from which I can get ‘wood’”). In this way, we sacrifice the sensible – that is to say, reality itself, which is always pre-linguistic – to our own glory. Put differently: we profane it.

It is therefore the sensible that we must recover and explore afresh. This seems to be more or less evident in today’s philosophical discussion, which, once and again, turns around notions like the return of the “sensible,” the “body,” the “affective,” etc.

While acknowledging that this is essential indeed, we would like to point here to something else, something that, together with the sensible, seems to have vanished as well from our lives: pure thought.

By pure thought we mean something different and something more than putting together whatever views and deducing from it whatever conclusions, which merely amounts to what the ancient Greeks called λόγος (logos, that which bounds together) or διάνοια (dianoia, composite vision). We mean something which was called νοῦς (nous) in ancient Greece, something whose Latin translation as intellectus is already misguiding and ultimately inappropriate, as intellectus derives from the verb intelligere, which means to choose between several things: inter (between) legere (to choose), similarly then to the term ratio (reason), which means to reckon, to number, to calculate, and which is frequently used in Latin, in consequence, to translate the Greek term λόγος.

Our thesis, then, is that the disappearance – the vanishing – of the nous is as terrible as that of the sensible, despite the fact that it, in contrast, is seldom acknowledged.

But what exactly is the nous? And how have we lost it?

An example will suffice perhaps to make clear what the nous is. Take Descartes famous formula: “I think, therefore I am.” Much has been written against it in the recent history of philosophy: “couldn’t Descartes feel that he had a body and deduce from it his existence instead?,” “is it that we are because we think?,” and “is it then that if we don’t think we are not?” A verdict has been provided, as well: “Descartes was an idealist,” idealism being, as per its conventional definition, the substitution of reality by thought.

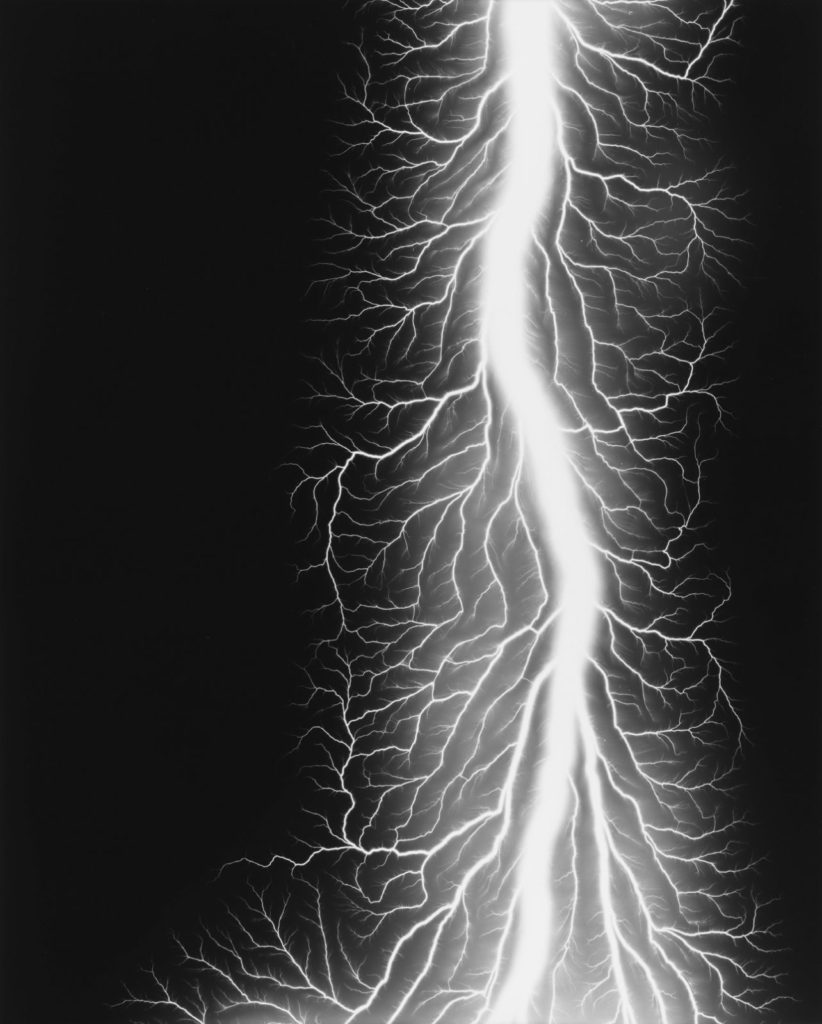

Spinoza reminds us however that Descartes formula is in fact more complex: “I doubt, therefore I think, and therefore I perceive myself as a thinking thing.” This is a composite formula: “(A) I doubt… (B) therefore I think… (C) and inasmuch as I do, I therefore perceive myself as a thinking thing.” As such, it implies reasoning, and thereby a segmentary succession: A → B → C. Reason (ratio, logos) is at stake here, then. But there is something beyond the formula itself – something under it, something behind it – that is simple instead. Like a flash of light.

Try to start thinking. Concentrate on it. It may well happen that, sooner or later at some point, you perceive yourself thinking, and hence as thought, or as a thinking thing. There is no succession there: it can only happen at once – if it happens. In other words, the recognition at stake there is an event, and as such it can only happen now, it can only be instantaneous; it takes place in time, but in the type of time the Greeks called αἰών (aion) in opposition to χρόνος (chronos), the time of the now – a time which is both instantaneous and eternal (aion has both meanings), since it eludes succession (chronos).

Descartes and the aion-vision – Descartes and the nous(*).

In like manner, a small child, when presented circular things – more precisely, things that we, adults, call circular, like a wheel or a coin – does not initially realise their circularity: s/he may, instead, pay attention to their texture, brilliancy, etc. The realisation that all such things are circular constitutes an event: it happens all of a sudden, in a certain now (aion).

Now, it is this singular event that Plato calls εἶδος (eidos, pl. εἴδη, eide), a concept that we usually render as the “idea,” or else, with the help of a paraphrasis, as the “intelligible aspect” of something. But it would be far better to say the “thought-vision” of something, since we have seen that terms like intelligible, intelligibility, etc. are at odds with the visions procured by the nous, inasmuch as these lack succession: they are simple and instantaneous, they take place at the speed of light.

Plato knew too that mathematics is a good way of becoming familiar with what we may therefore call the eidetical or the noetic. That is why he put a sign on the entrance of his school, the Academia, that more or less said that those uninterested in mathematics should not enter there. Surely this was not for Plato a prescriptive issue, but a reasonable one: if you dislike mathematics, you can hardly be attracted to philosophy, which pushes even further the same type of thought that underlies geometric calculations (the vision that this is a circle, that a triangle, and that something else a square rather than a pentagon, etc.).

It is too often, especially over the past two centuries, that Plato has been accused, due to what is commonly called his “theory of ideas,” of being responsible for the intellectual appropriation of the Real and, therefore too, for the sacrifice of the sensible that has been prevalent throughout the history of Western thought, or as we, philosophers, say, of Western metaphysics – in the sense of that which is after or beyond (μετά, meta) the physical. Yet this is an unjust accusation.

For Plato did not dream with, let alone encouraged, the sacrifice of the sensible, or its postponement on behalf of empty universals (the ideas of this and that, rather than the things themselves). One only needs to read his dialogues to realise the importance Plato conferred to both the sensible and the singular (the precise moment in which a young flute player enters a room, a laugh that irrupts in the middle of a conversation, etc.). What Plato discovered is the possibility of adding a supplementary and fascinating dimension to our perception of reality: abstraction.

It is Plato’s latter caricature, as well as Plato’s appropriation by later, specially Christian, thinkers – in short Platonism – that is to blame here, not Plato. For even though Plato discovers the nous, or, better, even though he thematises it for the first time, he does not divide reality into two halves, contrary to what we all have been taught. Of course, reading Plato against his misguiding traditional image requires good doses of sensitivity and sophistication, but Plato’s scholarship is full of both today(**). And it would be important not to blame Plato, or Ancient-Greek philosophy more broadly, for something that only with the irruption of Christianity first, and then modernity, became not only possible but also desirable: the domination of the world.

Furthermore, from Parmenides to Spinoza, Kant, and Schelling – to only mention a few names – philosophy has always involved thought intuition to one degree or another. Actually, there is no philosophy without it. Take, for instance, Parmenides’s identification of thought and being, Spinoza’s third genre of knowledge different at the same time from the imagination and demonstrative reasoning, Kant’s parallel distinction between Reason and Understanding, or Schelling’s concept of pure thought: they all point to something that lies beyond the argumentative skills of the mind.

How have we forgotten about it, then?

Very simple.

Just like Christianity (A) came to portray human inner life as being permanently subject to religious morality, so that whatever one felt, wished, and did had to be classified as either virtuous or sinful according to its own moral standards (“how much does this approach me to God?,” “how much does it distance myself from him?”), it determined too (B) that our mind must also turn towards God through the study of the external world by (C) following three basic rules:

1) Acknowledging that there is something like a universal sensible experience (“if I approach my hand to this fire, it gets burnt”);

2) Inferring from it a universal principle of cause and effect (“fire causes things to get burnt”);

3) Deducing from this law, in turn, a likewise universal law (“therefore, whenever I approach a fire, I will get burnt”);

that should help us reach the notion that in the same way that all things have their cause, there is one first cause of everything: God, whose existence can be proven by remounting the causal chain.

This is what was called in the Middle Ages natural theology (theologia naturalis). As you see, it is based on the ability of the mind to make connections – regardless of the fact that the reasoning itself is biased, since it presumes the existence of that which must be proven: God, which is why philosophy was transformed in the Middle Ages into a servant of theology (philosophia ancilla theologiæ). In this sense, it is fair to say that in the Middle Ages pure thought became less important in philosophy than it had formerly been.

As Schelling observes, moderns have refused from A and B, but have kept C intact under a new name: that of modern science. And have made of the latter such powerful and uncontested idol(***) that we have been persuaded that thought cannot do anything on its own but to deduce laws and principles from our sensible experience. In fact, this together with ethics – what in turn witnesses to the prolongation of Christian morality by other means – is what is called philosophy tout court in the Anglo-American world. Anything else is understood to be speculation, and thereby confined a place where it is a priori disempowered: art and/or literature.

In turn, those who rightly rebel against modern reason often tend to concede too much to the enemy, and, dismissing thought altogether, which they take to be a logical-normative prison made of rules, frequently opt for irrationality; or else they reclaim the freedom of the body from its rational-utilitarian appropriation, reminding of the need to recover the sensible.

And in this way, both moderns and their opponents ignore, and ultimately deny, the freedom of pure thought, of pure thought at the speed of light – the creative freedom of the mind understood as nous.

(*) Through which Descartes furthermore discovers the I as a pure intuition of thought. Needless to say, the I is also other things: (1) a synthesis produced by our reason or logos, that attribute the multitude and variety of our life-experiences, feelings, and thoughts to a more-or-less constant, if never once-and-for-all fixed, subject, in the sense of that which stands beneath (subjectum), without which no conscious life would be possible; (2) a somewhat-oversimplified, unifying notion that, if we cling too rigidly to it, may, nonetheless, prevent us from experimenting reality in less-self-centred, or more-adventurous, ways; (3) a despot, whenever we try to submit reality to our own will, determining that things must be like we like them to be and not allowing ourselves to resonate with the world; and eventually then, therefore, (4) a prison that disables us to be conveniently exposed to, and properly connect with, the outside. Refusal of 3 and 4 and engagement with 2 need not imply, however, a parallel rejection of 1, which is not a fiction but an indispensable living-device and stands at the root of linguistic pronominality.

(**) See e.g. Drew A. Hyland, Plato and the Question of Beauty (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2008).

(***) So much so that Nietzsche suspects that the modern scientific endeavour is a religious, and more specifically Christian, thing after all.

Further reading: F. W. J. Schelling, Ausarbeitung der Reinrationalen Philosophie [Exposition of Pure-Rational Philosophy], that is to say, Schelling’s latest work, which he wrote as an appendix to his Philosophy of Mythology. Sadly, it has not yet been translated into English, despite the fact that it is a key text in the recent history of philosophy – and for imagining afresh philosophy’s future.

Hiroshi Sugimoto, Lightning Fields 225 (2009)