I

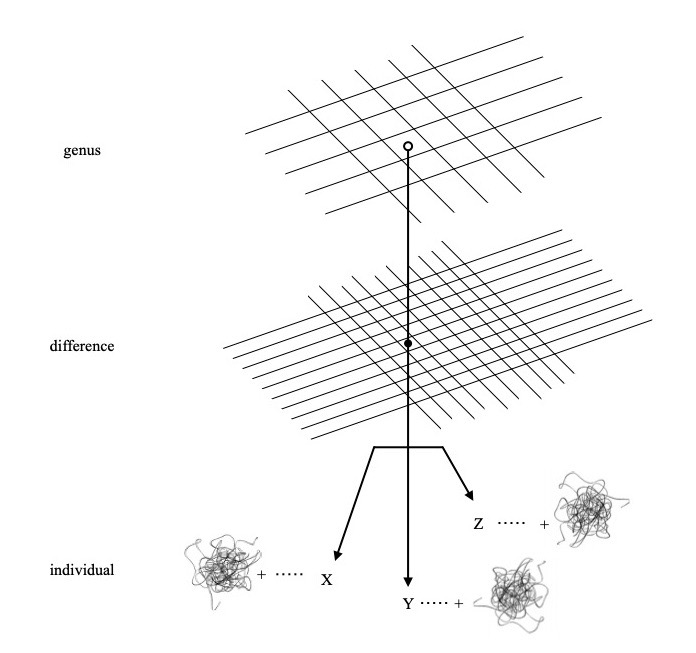

Unlike what Deleuze (1990, pp. 253-66) claims, it is not Plato but Aristotle (in An. Pr., I, 27) who reduces the individual to typological classification (this is an individual mango tree, mango trees belong in the mangifera genus, which are part of the anacardiaceæ family [fig. 1], etc.), which means that, from Aristotle’s standpoint, what escapes taxonomy (differences in themselves, to paraphrase Deleuze 1994, pp. 28-69) cannot be thought of but negatively as some kind of mess and remaining ultimately unthinkable.

In other words, it is Aristotle’s taxonomic thought or rack-thinking (as illustrated in fig. 2, one of whose visual motifs we have adapted, as the reader will easily recognise, from Paul Klee’s notebooks, although we have slightly modified its form here and there to make the same motif stand for three different pre-designable cum indescribable things), it is Aristotle’s rack-thinking that, in a certain sense, paves the way to the “positioning” (Ge-stell) of what is as a “standing reserve” (Bestand) of things characterised by their “assured [intelligible] availability” (Sicherstellung), to employ Heidegger’s well-known terms (ibid., pp. 1–73). In a certain sense, for classification is not a problem per se (Lévi-Strauss 1966, pp. 1–34, plus see our reference below to nominal classification in the Bantu languages); and, pace Heidegger’s (2012, pp. 60–1) ambiguous suggestion thereof there is no direct sequence between φύσις and Ge-stell.

Plato’s concern is somewhat different. Undeniably, there is Plato’s fascination with mathematics, which unravel the construable presence of something-other-than-what-we-ordinarily-see in what we ordinarily see, and of something regular for that matter. With it, we have the eidetic added to the perceptual. Plus, Plato transforms the eidetic into what accounts for the being and intelligibility of the perceived (note: like in Aristotle) and qualifies the eidetic as being even more real than the perceived (which is the target of Aristotle’s protest). But what does Plato mean with this?

If one puts aside Plato’s rhetoric (which amounts to a highly sophisticated problematisation of thought’s transcendental nature which is radically obscured when it is turned into a doctrinary exposition about thought’s alleged separatedness), it is not difficult to see that Plato is guided, above anything else, by a willingness to understand how is it that we come to think in the first place.

This is already patent in Hippias Major and elsewhere in the early dialogues. But the first key passage thereof it is Phaed. 100e–102e. What do we find in it? The notion that it would be impossible, for example, to say that anything resembles anything else at the expense of bearing in our minds an idea of equality which will always remain relative (i.e., proportional) albeit simultaneously unchanging (i.e., identical to itself or incapable of becoming a different notion).

In rigour, there is no contradiction in this dual affirmation. Socrates argues that things are (i.e., that we say they are) “big” and “small” because of the idea of “bigness” and the idea of “smallness,” respectively; and not, therefore, because of the size, say, of someone’s (X’s) “head,” which might be bigger than someone else’s (Y’s) head, but also smaller than someone else’s (Z’s) head (100e–101b). This moreover entails that one may well be “big and small at the same time,” in the sense that one (X) can be both bigger than someone else (Y) and smaller than someone else (Z) (102b). Notice that, against what is commonly assumed, this amounts to admit the situatedness of all εἴδη qua predicates. A different thing altogether is that an εἶδος as such (i.e. qua concept) can neither be turned into its opposite nor can it be exchanged for any other unrelated εἶδος (102d-3), as otherwise thought would be impossible to begin with.

Furthermore, the difference we have have just traced between εἴδη as concepts and εἴδη as predicates could supply a new theoretical framework for a post-metaphysical interpretation of the Platonic difference between “originals” and “copies”.

Additionally, in both Phaedrus and Republic Plato shows that, even if he is thinking (as usual) about something else than φύσις, he is not, however, turning his back on it.

Let’s examine more closely in this sense the term εἶδος, around which Plato’s philosophy revolves but which is already in Homer.

If, in Homer, εἶδος denotes what appears before one’s eyes, and only to that extent its aspect, it also denotes something’s beauty, i.e., something’s inherent gleaming. In fact εἰδάλιμος, from the same root as εἶδος, means “comely,” i.e., “pleasant to see” or “with beautiful appearance.” Plato seems to bear this in mind when, in order to delimit the eidetic conceptually, he equates it with that which is ἀληθέστατον or “most disclosed” (Rep. 484c) and φανότατον or “most shiny” (ibid., 518c) – a term which is morphologically connected to that by which he elsewhere describes the beautiful: ἐκφανέστατον, i.e. the “most shining forth” or “self-showing” (Phaedr. 250d). Now, φανότατον and ἐκφανέστατον relate to the verb φαίνω, to “shine,” to “appear”; whereas εἶδος relates to the verb εἴδομαι, to “appear before one’s eyes.” Hence φανότατον (and similarly ἀληθέστατον) confer(s) its latitude on the eidetic, which is not merely formal, let alone categorial.

Put differently: Plato’s eidetic domain is still translucent to φύσις, which is why Plato draws on words that are reminiscent of φύσις’s gleaming (cf. Heraclitus, DK B30).

II

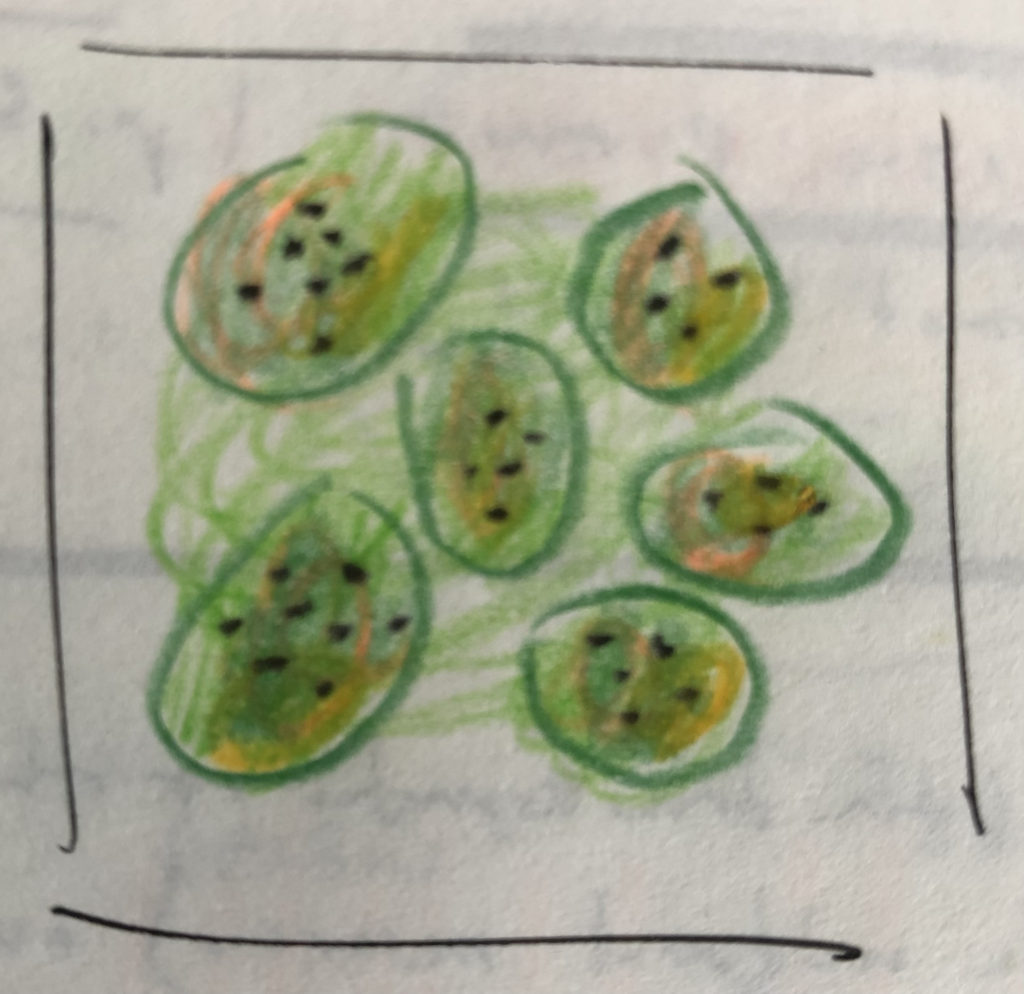

Think, for instance, of a mango tree (fig. 3). One ought to ask what actually happens when one exclaims:

“This is a mango tree!”

A sort of amazement guides this eidetic saying, in which an earth’s mango-like-coming-into-being happens. But this is the same as to say that the mango-tree εἶδος names a “φύσις-event” that is celebrated in the seasonal collecting of its mangos. In other words, the mangos are the ever-living reminders of a unique but ongoing event: the mango-like-coming-into-being of the earth, whose witness is the mango-tree εἶδος, thereby produced (like another type of fruit: ours) less to grant our control over what things are than to allow for their care.

In short, the mango-tree is an “event”; the mangos, the “reminders” of that event; and the mango-εἶδος, its “witness” and our own “thoughtful” (in the two senses of the term: thinkable and caring) “fruit.”

At the expense of the latter… reality would still be undeniably sensed, but would also remain unknowable (fig. 5) and be at risk of not being cared for. Hence, Aeschylus’s conviction that justice stands in direct proportion to knowledge (cf. Severino 211–17; Marzoa 31–9).

III

Arguably, on the other hand, all εἴδη are the product – the effect – of a complex “analogical flow” (Wagner 1986, passim) of meaning that brings to the fore analogies and differences at the same time, as we have suggested at the outset of this post regarding the mangoes, the mangifera, and the anacardiaceæ. Bantu languages offer an extraordinary example of this, as in them nouns go, as a rule, preceded by a class prefix, and nominal classes are often construed after situated visual analogies; yet what follows such prefix (the noun proper) differentiates the thing in question from all others belonging in the same class. Compare to this our analysis of Bororo nouns in “Metaphor and the Analytic-Philosophy Cuisine.”

Is it possible, then, to reconcile the view that all εἴδη are the effect of an analogical flow with Plato’s notion of ἀνάμνησις? We think so, provided, that is, the latter is not taken literally; for an εἶδος-event is, precisely, an event: one in which, all of a sudden, an image appears (and then reappears) in the mind leaving no trace of the flow of which the εἶδος is, so to speak and in another sense too, the fruit.

References

- Deleuze, Gilles (1990): The Logic of Sense, ed. Constantin V. Boundas, trans. Mark Lester and Charles Stivale; London: The Athlone Press.

- Deleuze, Gilles (1994): Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton. London: The Athlone Press.

- Heidegger, Martin (2012): Bremen and Freiburg Lectures: “Insight Into That Which Is” and “Basic Principles of Thinking,” trans. Andrew J. Mitchell. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1966): The Savage Mind (La Pensée sauvage). London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Martínez Marzoa, Felipe (2006): El decir griego. Madrid: La balsa de la Medusa.

- Severino, Emanuele (1989): Il giogo. Alle origine della ragione. Milan: Adelphi.

- Wagner, Roy (1986): Symbols That Stand for Themselves. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.