The real question is not whether the touch of a woodpecker’s beak does in fact cure toothache. It is rather whether there is a point of view from which a woodpecker’s beak and a man’s tooth can be seen as “going together” (the use of this congruity for therapeutic purposes being only one of its possible uses), and whether some initial order can be introduced into the universe by means of these groupings. – Levi-Strauss

The Nature-Culture Shift

This is a post on extra-modern magic. The designation “magic” is anything but inoffensive, though, in the sense that it involves the interpretation of a phenomenon whose nature, instead of being taken for granted, ought to be clarified in the first place. So it would be possible – or rather, it is perhaps necessary – to substitute “magic” for “X.” Back to the outset, then: this is a post on extra-modern “X,” where “X” stands in lieu of what we customarily call “magic,” to which, also customarily, we attribute a reality that may well tell us about ourselves more than about the phenomenon itself.

Let’s begin with a dual definition taken from Viveiros de Castro, which we find useful to slightly reword. It points to Amazonian extra-modern peoples, but it can be made extensive elsewhere (in America, Africa, Asia, Australia, and Oceania): “a person’s body indexes her constitutive relation to bodies similar to hers and different from other kinds of bodies, while her soul is a token of the ultimate [relatedness] of all beings, human and non-human alike.”(*) In other words, there is consanguinity and physics (what one is and thus how one should be classified) on the one hand, affinity and metaphysics (what one can relate to and transform into, so as to become more than what one is) on the other:

I am a “…” (fill at will with any so-called ethnonym) but I can become a jaguar to be a better hunter, and, if I do, I will then see all things (my fellow “…” included) as a jaguar sees them – not very different from how I now see them, only that I will be seeing other things in their place, for what I see as my blood the jaguar sees it as manioc beer, just like the parrot sees other parrots as humans and humans as parrots, etc.); which is also the reason for which theriomorphic becomings(**) prove as fascinating as they prove dangerous.

But why this duality, which has certainly nothing to do with the Western soul/body dualism? Because, as Viveiros de Castro himself highlights paraphrasing Roy Wagner, “the primal analogical flow of relatedness” that structures the world as an intersection of reciprocal (i.e. inverted) perspectives “is a flow of spirit,”(***) whereas identities are body-based instead: I am a “…” while any jaguar is a jaguar, as our different bodies prove.

Once more then, by way of recapitulation: on the one hand, there is consanguinity and physics (what I am); on the other hand, affinity and metaphysics (what I can transform into so as to become more than what I am).

What we call extra-modern “magic” belongs in the second class. For it transforms bodies into souls, or substances into relations, i.e. physics into semantics. Let’s see how by means of an example.

But, first of all, before we go into the example, we must stress that by turning physics into semantics, “magic” performs nothing different from what “culture” performs when it makes possible and encourages to cook the raw, or establish such and such dietary prohibitions that forbid to eat no matter what, or to determine whom one cannot marry, or to use such and such objects for such and such purposes, or to confer such and such symbolic functions to such and such colours, or to assign meaning to otherwise meaningless phonemes.

“Magic,” therefore, is just – to employ a metaphor – one of the many mirrors where to observe what, echoing Lévi-Strauss, Roy Wagner(****) calls the “nature-culture shift,” i.e. the transformation of what is given into something else, a transformation that amounts to the semiotisation of the given (α) in one way or another (→ αn), but always in some particular way (αx, ay, αz, etc).

Un-naturalising the Modern View of Things

Now the example, whose main motif we extract from Sylvie Poirier’s ethnography.She recalls that, in the early 1980s, the politics of conversion to Christianity in the Kimberly District and its surroundings in Western Australia became slightly more tolerant than it had been till then, so that the converted Aborigines’ ongoing attachment to their ancestral “Law” was no longer reprimanded by the ecclesiastical authorities, but welcome into the church; as a consequence, the Aborigines found it possible to somehow mix two “Laws”: the “Law” of the church and their own “Law.” Thus, for instance, after mass baptisms traditional ceremonial camps would be erected to gather “intense ritual activities under the umbrella of the ancestral Law.” Occasionally, however, this admixture proved problematic, as an episode occurred in 1987 evinces. Poirier describes it thus:

In 1987, the Catholic diocese organized a religious meeting in Broome to which a number of communities from the Kimberley area were invited. A group of about fifteen people from Balgo accompanied the church people. Among them, a young man, involved then with the church, travelled to Broome in an old car he had just bought and which, as it turned out afterwards, was in rather poor repair. Accompanying him were his pregnant wife, their children, his mother and father, and his classificatory mother, the first spouse of his father. On their way back, in the vicinity of Halls Creek, they had an accident in which the young man’s classificatory mother (a Walmatjari elder from Mulan) was killed. The news of the accident and of the death reached Balgo only the following day. At once, crying and wailing started echoing in the top and bottom camps. It went on all night. Early the next morning, their faces and chests painted with kaolin as a sign of mourning, and the men armed with their boomerangs, the men and the women from the top camp walked towards the bottom camp where they were awaited. There, the close kin of the deceased and those of the young man formed two lines and confronted each other with boomerangs and insults. This animated expression of grief lasted for a few moments, after which everyone sat down and gathered to cry and wail, sharing their sorrows. The female close kin of the deceased injured themselves by hitting their heads with stones or any other convenient hard objects, while a few of the male relatives had speared their thighs the previous night in the intimacy of their camp or in the bush. These moments were the preludes to the ‘sorry business’ (mourning ceremonies) and to a ritual of conflict resolution that was to be held a few days later.

From the Kartiya point of view, one of the causes of the accident was the car’s poor state of repair. In addition, the police accused the young man of drunken driving and of driving without a licence. On the other hand, Aboriginal causality and objectivity required that the explanation for this sad event had somehow to be found elsewhere. In the days following the accident, as the atmosphere overflowed with grief, discussions, speculations, and interpretations were offered as to the causal chain of events that might account for the death. Nungurrayi, a very respected Law woman, perceived in this unfortunate event the confirmation of their own mistake in bringing their own Law into the church. A few people seemed to agree with her, though no one else expressed it in such an explicit manner. This is what she said: “Nobody can stop us thinking. We can think long way. For long time we kept the Law in the camp, for us. Before we never used to mix up. Now we been mixing. We been bring some Law in the church. This is no good.”

Two days after the accident, the young man was released from the Halls Creek prison, awaiting his trial according to Kartiya law. The young man was held responsible for the death of his classificatory mother and, in order to alleviate the grief of the deceased’s relatives, he had to be punished according to Aboriginal Law. A ritual of conflict resolution had to take place. Everyone in Mulan, not only the relatives of the deceased, was strongly affected by the death. Considering the intensity of their grief, the family of the young man feared the worst. On the fourth day after the accident, a few hundred people from Balgo and Mulan gathered at the bottom camp for the ritual of conflict resolution. While the young man stood in the middle, his brothers – and also the sons of the deceased – real and classificatory, formed a half- circle around him. Over the next few moments, they threw spears and boomerangs at him. He protected himself with a shield, which he handled awkwardly. During the attack, his cross-cousins were allowed to protect him, which a couple of them did. His mother and one of her sisters ran by his side and succeeded in intercepting a few blows. The intention was certainly not to kill him, but the whole performance was necessary in order to give a lesson to the offender and soothe the pain and grief of the deceased relatives. The young man received a head injury, and it was the two sisters of the deceased who afterwards cleaned it and comforted him. The conflict was over, and the mourning ceremonies were held two days later in Mulan. The whole of Balgo and Mulan participated alongside relatives of the deceased who had come from Billiluna and Christmas Creek. A few weeks later, the young man had to face the Kartiya law and was sentenced to a few months in jail.(*****)

Why did the “respected Law woman,” one may ask, interpret the “accidental” death of the Walmatjari woman as a “confirmation” of what she took to be their own “mistake” of bringing their ancestral “Law” into the church, that is, why did she link two apparently unrelated things, the woman’s death (let’s label it “D”) and their alleged wrongdoing (“⧲”)? Put differently: what led her to attribute some sort of “magical influence” to ⧲?

The typically-modern response is: “superstition,” i.e. “irrationality,” as from a typically-modern perspective (i.e. from a post-oracular Western perspective) there is no intrinsic connection between the two things, one of which, moreover, can be said to be a fact (namely, “D”), while the other one (“⧲”) stands, merely, for a subjective impression.

Yet what appears to be rather “natural” and “objective” to the modern eye (the un-relatedness of both things) is anything but objective and natural: it rather implies an unrealised prise de position, i.e. an unconscious interpretative decision, in short, an a priori way of looking at reality and of defining what reality is – one among others.

The woman reads “D” as supplying an opportunity to reflect on what may be “right” and what may be “wrong” in relation to the group’s doings, as it is only by determining what falls under each category (how else indeed?) that the group will have the possibility of learning about the moral relevance of their actions. In a word, learning demands thinking, and thinking demands distinguishing what is right and what is wrong concerning one’s doings; no community can survive without permanently reflecting on it. Accordingly, “D” works as a catalyst for that reflection, the result of which is, precisely, the determination of a specific behaviour (the admixture of the two “Laws”) as “⧲,” i.e. as a mistake.

Against this, the typically-Western mentality displays its cynical indifference towards what is: whatever happens is unrelated unless it is “mechanically” related; technically speaking: “facts” and “values” are unconnected (Hume), and thereby “magic” is disproven.

When Things Are Good to Think With

So far, the example supplied by Poirier.

Let’s now imagine a different case in which an extra-modern group takes the initiative to harm a person deemed “responsible,” on account of her typified moral wrongdoing, for an event or a situation declared by the group to be “pernicious,” like someone else’s physical illness.

Again, for a typically-Western mentality, the connection between “facts” and “values” would be meaningless, and the person’s punishment, consequently, arbitrary – a sign of “irrationality.”

Yet here, too, things prove more complex than they seem at first sight to the modern eye. For the modern, mechanicist mind is only ready to think “causality” in “efficient” terms. If someone “causes” something, it can only be like when you kick a stone with your foot. There is no way, therefore, in which one can provoke something physical to happen by acting in an unmoral way which, on the other hand, someone else may not find unmoral at all. Mechanicism and individualism thereby converge in dismissing extra-modern “magic” as being not only “irrational” but also “intolerant,” i.e. twice unrefined for the modern taste. After all, says Locke, “every one does not place his happiness in the same thing”; yours can be placed, for instance, in improving hydraulic fracturing techniques for the extraction of petroleum in expropriated indigenous land.

However, when, within an extra-modern group, someone is viewed as being morally faulty for something as well as being, due to it, responsible for a physical calamity suffered by someone else, it is generally in metonymic terms. Put differently: the relation of “causality” thus established is metonymic rather than efficient, or indexical rather than substantial.

Once more, a particular situation (let’s label it “F”) prompts the group reflection along the lines formerly explained: “F” and “⧰” belong in the same class, and, for that reason, “F” can be seen as a index of “⧰,” just like “⧰” can be seen as a index of “F”; both indexes are partial of course, in the sense that there is much more in “F” than its pointing to “⧰,” and much more in “⧰” than its pointing to “F”; and because they are partial, their relation is metonymic – no more, but certainly not less either.

Any Tarot player knows it: if a card is meaningful in whatever way (and they are all meaningful in one way or another) it provokes reflection and thus can be interpreted somehow. And this is not very different from what the philosopher known in turn: if something is good to think with, it automatically becomes an object of thought and, thereby, something susceptible of being connected with a number of other thoughts, namely, those somehow capable of being classified together with it.

Also, any lived life responds to this logic, since life’s cards are always given to us; we just choose how to play them.

But then, what about the aforementioned punishment? Is it necessary? Evidently, nothing is. Life is improvisation. Even in societies in which each person is assigned a number and each gesture a code – that is to say, even in our modern societies. Hence even more so among extra-modern peoples:

If Americans and other Westerners create the incidental world by constantly trying to predict, rationalize, and order it, then tribal, religious, and peasant peoples create their universe of innate convention by constantly trying to change, readjust, and impinge upon it. Our concern is that of bringing things into an ordered and consistent relation – whether one of logically organized “knowledge” or practically organized “application” – and we call the summation of our efforts Culture. Their concern might be thought of as an effort to “knock the conventional off balance,” and so make themselves powerful and unique in relation to it. […]

The conventionally prescribed tasks of everyday life, what one “should” do in such a society, are guided by a vast, continually changing and constantly augmented set of differentiating controls […] These include all manner of kin and productive roles, magical and practical techniques, possible modes of conduct for personal deportment. And if the ethnographer finds it difficult to standardize these controls, or catch a “native” in the act of explicitly “performing” one of them, it is because their very nature and intent defies the kind of literalness that “standardization” or “performance” (as well as the ethnographer’s own professional ethic of consistency) implies. They are not Culture, they are not intended to be “performed” or followed as a “code,” but rather used as the basis of inventive improvisation. […] The person who is able to do this well – even to the point of inventing wholly new controls – is admired and often emulated. The controls are themes to be “played upon” and varied, rather in the way that jazz lives in a constant improvisation of its subject matter.

And so we can speak of this form of action as a continual adventure in “unpredicting” the world.(******)

Yet the possibility that the punishment is carried through must not be discarded. So let’s suppose it materialises. Would it indicate anything but the gathering of the group around, and its self-strengthening before, a term implied in a metonymic relation, and arguably, then, its own metonymic positioning vis-à-vis that which is perceived by the group as constituting its own disruption? In other words, would it express anything but the conjuring of a threatening otherness, and would such conjuring not work as a suitable supplement to the group’s learning?

A Question of Divergent Logics

Too many relations. Too many. Things tend to be over-interpreted in proportion to their being over-related, etc.

It is easy too fancy these and other similar objections. But then again, who has decided that it is better not to think so much? Our survival is granted by public and private healthcare systems. The survival of extra-modern peoples is granted by thought alone. That makes a difference – and it is far from evident that our lives are better than theirs (in terms of health, to begin with).

Well, perhaps – but does not this open the door to arbitrary abuses of all sorts, you may ask? Actually it does not. In fact extra-modern groups are stable by means of being egalitarian, and life inside them is livable for that very reason. But on this we have written elsewhere.

When living is living with instead of being enclosed in your own niche (with your collection of individual rights, etc.) everything relates: the world becomes a world of relations in which live is permanently negotiated because of being – as we have suggested – permanently thought. Furthermore, only then it can be improvised, since in the absence of thought there is simply no chance to make it through.

Yet the temptation of suppressing all thought is there – who can deny it? And it becomes the current state of things when thinkable relations are replaced by formal categories into which reality is forced.

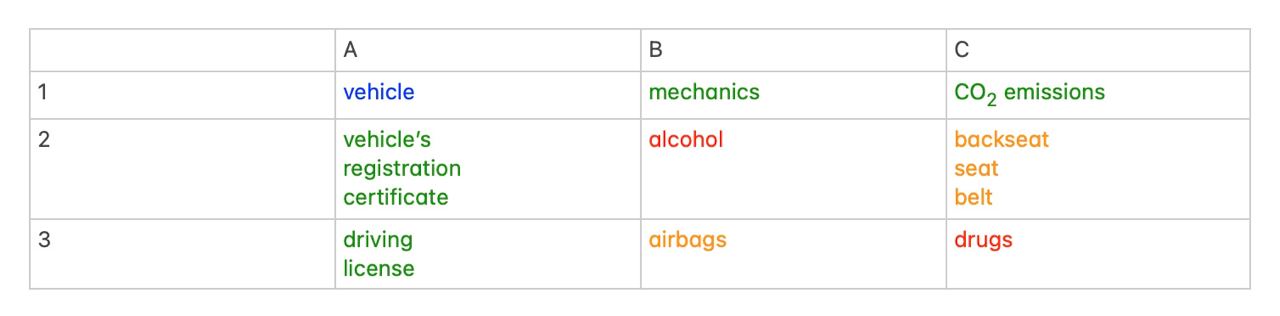

Consider, for example, the following table:

If you have a vehicle (A1), in order to drive it outside your home you must register it (A2) and a get a driving license (A3). Also, you must have it pass as many technical tests as may be needed to grant its mechanical well-functioning (B1) and an acceptable level of carbondioxhide emissions (C1). You will not authorised to drive it under the effect of alcohol (B2) or drugs (C3), though. And, depending of the country or state, you vehicle can be requested to have backseat seat belts (C2) and airbags (B3).

This table has nine boxes. If you have an accident in which a friend of yours siting in the backseat gets injured, it will all be about checking them all and about ticking them correspondingly ( ✔︎, ✘ ) to see what items/norms did you comply with and which did you not. Your driving license was about to expire. You should have taken a new psychotechnical test to renew it, which would have made you aware that you have lost sight. Besides, although your vehicle’s level of carbondioxhide emissions seems to be fine, the technicians have noticed a few problems with its mechanics, which you should have repaired before going into the road. Plus your vehicle does not have backseat seatbelts and you were driving after having consumed some alcohol. All this, together with the fact that a little bit of rain had reduced the visibility on the road explains the accident.

The modern mentality is satisfied with this reductive logic. It is a logic, though, that cannot satisfy the complexity and creativity, the richness and inventiveness, of the extra-modern mind, for which the world is thought afresh once and again, and for which, like in the case of Leibniz’s monadology, every piece of the world does not merely add to all others, but recapitulates the whole world in itself by means of the relations it can enter.

Or “magic,” if you wish.

(*) Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Relative Native: Essays on Indigenous Conceptual Worlds (afterword by Roy Wagner; Chicago: HAU Books, 2015), p. 145.

(**) On the ontology of animal-becomings and their metonymic qualities, see here https://polymorph.blog/those-whose-bodies-do-not-look-like-us/.

(***) Viveiros de Castro, The Relative Native, p. 145.

(****) In his posthumously-published The Logic of Invention (Chicago: HAU Books, 2019).

(*****) Sylvie Poirier, A World of Relationships: Itineraries, Dreams, and Events in the Australian Western Desert (Toronto, Buffalo, and London: University of Toronto Press, 2005), pp. 35-37.

(******) Roy Wagner, The Invention of Culture (revised and expanded ed.; Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1981), pp. 66-67.

Life consists in tracing an inevitably-zigzagging path (the green line) which oscillates between two eventually intersecting domains: the domain of the wanted (A, blue) and that of the unwanted (B, red), and which thought (the black line) intermittently accompanies more or less successfully, and all this always within a given cultural space (encircled in the diagram) capable of conferring meaning and value to otherwise disconnected facts. Image by Polymorph