For Pere Ros

Suppose a series of musical notes forming a melody (the black circles are the notes, the arrow indicates their succession):

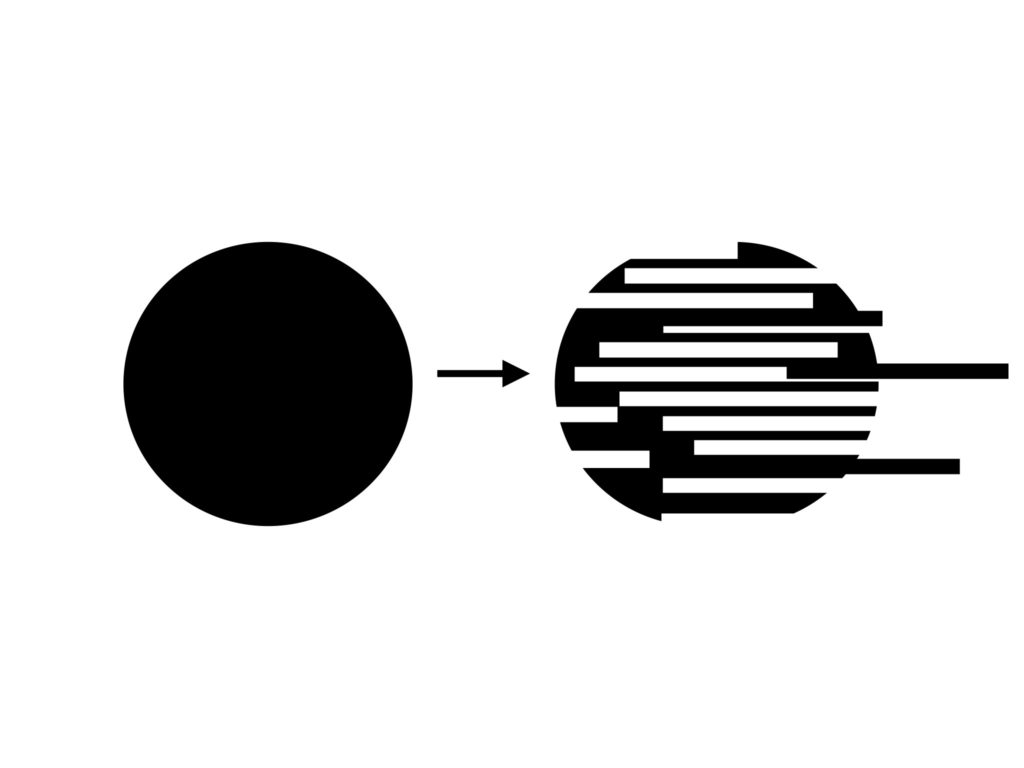

Suppose, though, that instead of hearing the notes sounding cleanly one after another, some of them were shaken by a gusty wind; as a result, such notes would “look” more or less like this (on the left side the natural note, on the right side the effect of the wind strikes on it):

Let’s call it the intermittent effect, effect no. 1.

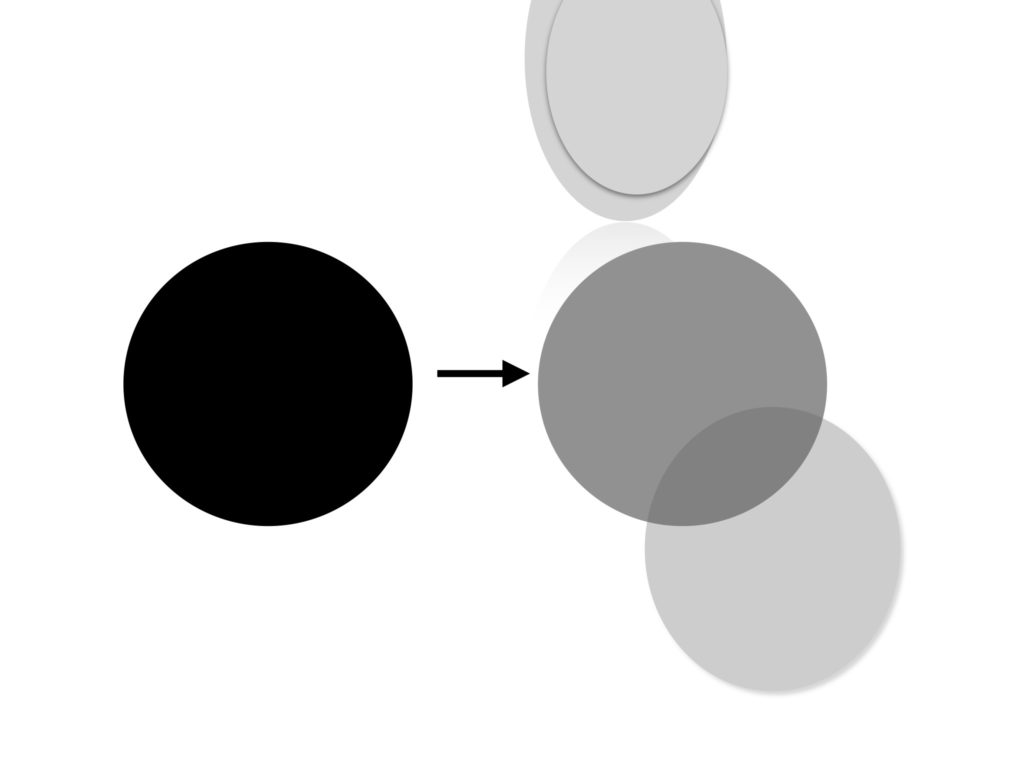

Suppose, too, that other notes were to dissolve themselves into their echoes, but that none of these were to reflect the note it echoes with complete exactitude, i.e. that a certain difference (in height, “texture,” timing, etc.) were to be perceived between each note and its corresponding echoes; as a result, such notes would “look” more or less like this (on the left side the natural note, on the right side the effect of its irregular multiplication):

Let’s call it the echo effect, or effect no. 2.

Lastly, suppose that other notes were to explode like fireworks whose fading traces would produce a cascade of new smaller notes (on the left side the natural note, on the right side the traceable effect of its explosion):

Let’s call it the outpouring effect, or effect no. 3.

In 1740 Hubert Le Blanc published in Amsterdam a treatise titled Défense de la basse de viole contre les enterprises du violon et les prétentions du violoncelle [Defence of the bass viol against the pursuits of the violin and the claims of the cello]. By then the viol was becoming, under the influence of the violin and its bigger brother, the cello, a démodé instrument. Harmonically rich but too complex melodically, the viol did not fit the new, simpler musical taste theorised by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his Dictionnaire de musique (1768) – a taste that maybe only with Schumann’s inexhaustible complexity and exquisite depth comes to an end.

Be that as it may, the three aforementioned effects – whatever their specific conceptualisation: we have just risked one among other possible ones – are among the most characteristic effects produced by the viol when played. This Allemande in D minor by Dietrich Stoeffken performed by Johanna Valencia illustrates it well enough:

In turn, this Prelude and Chaconne by M. de Machy in G major performed by Robin Pharo evinces the delicacy of the viol’s voice:

The revival of period instruments from the 1990s onwards has resurrected the viol’s repertoire and physicality, which we can thus enjoy and admire today. Yet something of its amazing beauty remains, as it were, submerged in the depths of a precious, not-fully disclosed world.

Had the sirens had a voice like hers, Ulysses might not have been able to resist their call and to remain long on board…