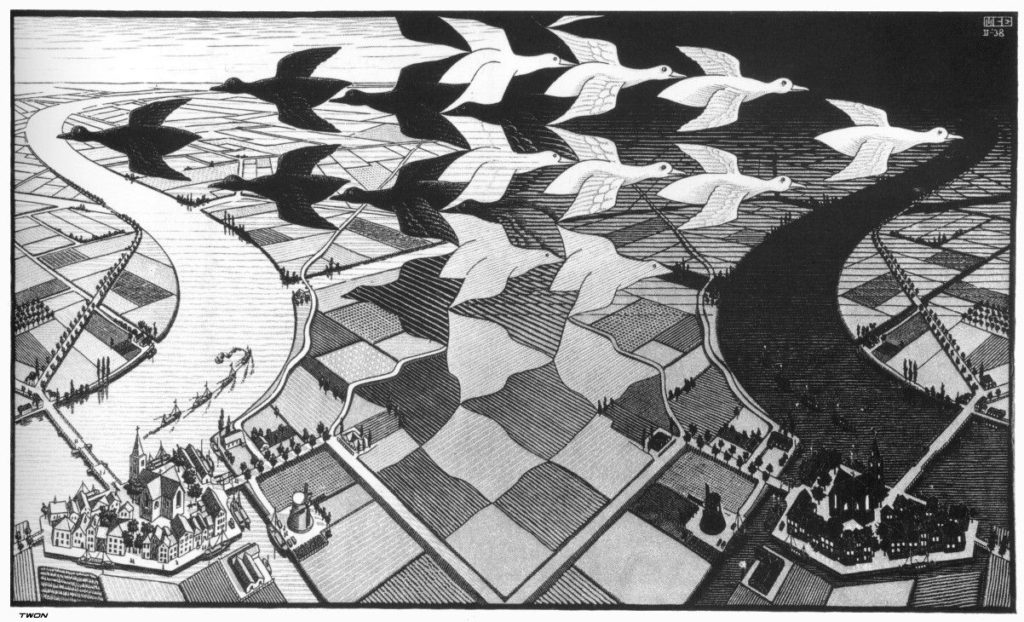

§1 • What is present cannot become past after being present, for that would mean it becomes past in the future. Rather, the present, any present, must be always passing, or, more exactly, given its thinness or inherently-ephemeral nature (the present never lasts long), it must unceasingly and simultaneously bifurcate itself in two directions (like M. C. Escher’s ducks split their flight in two opposite directions at approximately the centre of a print of his from 1938, titled Day and Night): one towards the past, the other one towards the future. But this means the past is not something simply gone, as, somehow, it must be always accompanying the present, as if it were its back.

M. C. Escher, Dag en Nacht (1938)

§2 • Nor does the future lie before us as that which lies after the present. Surmising it does and adding that it is either positively fulfilled according to our expectations (in utopian logic), negatively fulfilled according to our fears (in dystopian logic), or indifferently fulfilled who knows how, would be of as little help as to suppose that time has been fulfilled and therefore stopped. The future is permanently open, and it is permanently opened now: it is the present’s horizon, the horizon of every now.

§3 • Paraphrasing Baudrillard, who writes that “Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real, when in fact all of Los Angeles and the America surrounding it are no longer real, but of the order […] of simulation,” it can be affirmed that putting the future before us (in whatever way we choose to do so) is the best way to delude ourselves into believing that the present is complete and the past is no longer.

§4 • The truth is that the past, which is never simply gone, does not only resonate in the present but keeps it open as it is (and can even assault it: the abyss-like emergence of the past in Visconti’s Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa supplies an admirable example). The truth is that the present, in turn, either maintains or rejects the past’s legacy. The truth is that the future, lastly, is proportional to the carrying beyond or, alternatively, to the interruption (in form of reversal or side-walk), of the destiny thus bequeathed by the past.

§5 • All this means that to make a change in the past’s insisting legacy one must curve that legacy otherwise in the present, i.e. now.

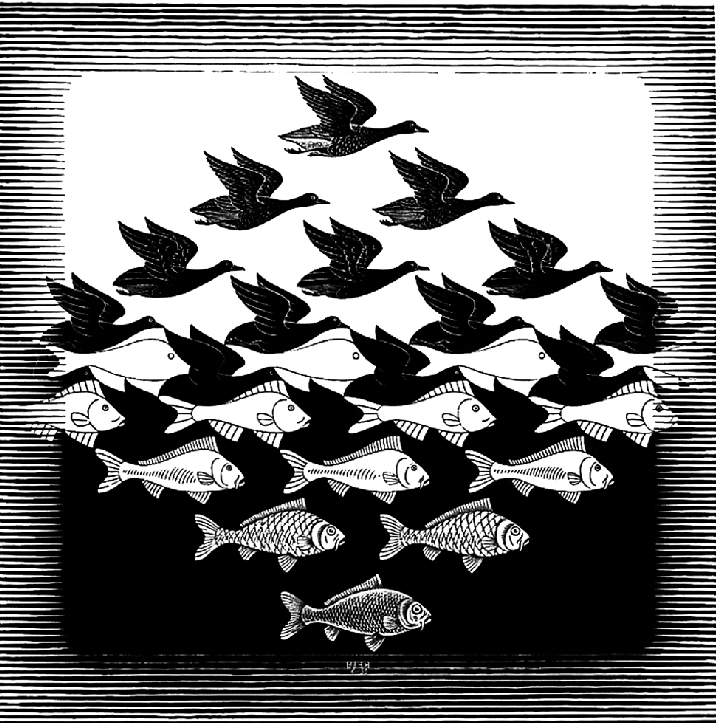

§6 • Yet, at the same time, any experienced present, every experienced now, is only an image, a reflection of another now which is no longer there, in the sense that our perception of any event follows it instead of being synchronous with it, as there is always a little time gap between the production of an event and our perception of it. Put otherwise, what we call present is actually the difference between those two asynchronous moments (which relate to one another like Escher’s ducks and fishes in another print of his from 1938, titled Sky and Water I).

M. C. Escher, Lucht en Water I (1938)

§7 • Thus we live an image, or inside a reflection of what is no longer present: a reflection that opens at the same time, like a revolving door, to a past that is never fully absent from it and to a future that is never exactly beyond it. We live in the untimely.