We want to talk about Plato. Of Plato as a modern taboo. Hence also about ourselves. About Plato and us. But first we are going to talk about horses. About apparitions and sculptures. Otherwise – we fear – we would only be able to repeat commonplace views on Plato. And we have had enough of them already. Instead, we want to understand Plato.

On Sculptures as Apparitions

Ancient-Greek sculpture often proves today cold and unmoving and too rational. But all things benefit from being put into due perspective.

A sculpture makes something visible. And it is safe to deduce that what becomes visible in the sculpture is visible because it “comes into the light”. In other words, a sculpture is a particular case of what the Ancient Greeks called φαίνεσθαι (phainesthai), “to appear,” hence (literally) a φαινόμενον (phainomenon), a “phenomenon,” an “apparition.”

The apparition of something amounts to its “shining forth.” How does a horse shine forth? Seen from an Ancient-Greek perspective, it shines forth when its “horseness” (what makes of any horse a horse instead of, say, a toucan or a lynx) becomes fully apparent. Thus the statue of a horse must not only look more or less like a horse, but transmit to the viewer the living qualities of any horse, including its strength and vigour, or else its tiredness, and eventually too, its nocturnal aspects.

For us, this is all about a horse’s descriptive qualities and about the skill needed to render them perceptible as something at the ready. Thus we think that Ancient-Greek sculptures are accomplished three-dimensional descriptions of what they represent. But for the Greeks they were something else.

What Is the Idea of Something?

Now, in Greek the word εἶδος (eidos, which we usually translate as “idea”) names (literally) something’s “visual aspect,” that is to say, the characteristic “appearance” of that something when that something “comes into the light” and thus becomes present in the realm of “being” (in the domain of what “is”) offering itself to be “perceived.” Hence in the case of a horse – to continue with our example – its “horseness.”

From this Plato suggests that the εἶδος (eidos) – taken, then, as the distinctive “shining forth” of each thing into the openness of its unconcealed standing-there “as ‘X,’” – may also be said to be:

(a) that which (truly) is (ὄν, on) in the thing in question;

(b) that which is (fully) intelligible (νοητόν, noeton) about it;

(c) that which can be said to be (really) beautiful, noble, and good (καλός, kalos) in it;

(d) that which is (thereby) desirable (ερόμενος, eromenos) for it, in the sense of that which the thing is moved by and that which it intrinsically aspires to;

(e) that which is (thereby too) lovable (again, eromenos) about it, in the sense of that which is desirable in it for others;

(f) (consequently) the good (ἀγαθόν, agathon) in it, in the sense of that which the thing attempts to achieve, so as to be what it is all the more intensely and as perfectly as possible;

(g) (consequently too) the good (ἀγαθόν, agathon) thing about it, in the sense of the good that it can offer to others;

(h) (hence) what confers unity to the thing making it appear as one (ἕν, hén); and

(i) (therefore too) that which is divine (θεός, theos) in it.

The Misunderstanding

There is, of course, the risk of turning the εἴδη (eide, pl. of eidos) into “formal archetypes,” i.e. into the models things must subordinate themselves to be what one expects them to be (a proper horse, a decent man, etc.). But while this has been a more-or-less-recurrent tendency in the history of Platonism (especially Christian Platonism), it is rather secondary for Plato – to say the least – to think in moral-juridical terms, i.e. in terms of what things ought to be and of the moral verdict that their being or not being such or such deserves (M is a good boy, N a bad one). Nor is the expression “idealism,” despite its currency, the best one to describe Plato’s hypothesis about the eide, which is not exactly a “theory.”

As we have advanced at the outset, we want to rethink Plato at the expense of any prejudice, which should not substitute for patient thought in the interpretation of a great philosopher.

What Plato Said and Why

The first thing one must be aware of is that Plato stands between the Presocratics and Aristotle.

Like the Presocratics, Plato is interested in the “shining forth” of things into the region of the unconcealed. Unlike the Presocratics, however, he is not so much interested in the shining forth “itself” that makes everything appear as he is in the shining forth of X “as X.” Put differently, he is not so much focussed on the “presencing” that makes things appear and be as he is on the becoming present of “X,” which is determined by “what” X “is.”

Yet even if it can be affirmed – as Heidegger says – that in Plato the shining forth “itself” is somehow forgotten in favour of the “presence” of X “as X,” it is important to realise that the becoming present of X as X is still in Plato the “shining forth of X” rather than the “lying at the ready of X,” as it will be in Aristotle. Nor is the “Xness” of X in Plato, in contrast to Aristotle, solely that which permits us to “classify” X as being different from Y and Z.

Therefore, it makes no sense to attribute to Plato preoccupation which are not his. Plato is concerned with questions of phenomenology and ontology, with how things appear to us and with what makes them perceptible as what they are, especially, if not exclusively, as regards what can be called human qualities: what does it mean to be virtuous?, what is to be just?, etc. If he is also preoccupied with politics it is in the conviction that thinking carefully about such qualities regardless of whether it may be possible to reach any conclusion about them, should help us to live together in a better manner.

An Example

So in which sense can it be said that the eidos “is” and that it is the “intelligible,” “beautiful,” “noble,” “desirable,” “lovable,” “good,” and the “divine” present in something, as well as that which confers unity to that something? Suppose, for instance, that X is a philosopher, plus a professor, plus someone’s lover, plus someone’s father and someone’s friend. The deeper and clearer X’s ideas prove the more X will be seen as a good philosopher. If, in addition to it, X teaching is appreciated by X’s students because of its brilliancy and commitment, and X’s research contributes in new and thought-provoking ways to a particular academic field, X will be acknowledged as a good university professor. Furthermore, if X is a passionate and devoted lover, and remains being a passionate and devoted lover for many, many years, X will be recognised as what, apart from being a good philosopher and a good professor, X also is: a good lover. And the same has to be stated apropos X’s fatherhood and friendship, respectively.

Now, will we not say that X “is” more of a philosopher, more of a professor, more of a lover, more of a father, and more of a friend in proportion to how good X proves to be in all such cases? And will we not say, moreover, that if, during a class, while discussing an important textual passage, X, instead of responding to the students’s questions and comments, spits on the board and runs away from the classroom, and, during the next class, he gives the students a two-hour exam, but after only five minutes he collects their papers and fails them all, will we not then say that X is anything but professor at all, and that it is hard to understand, in the sense that it cannot be sorted out and thus made “intelligible,” what X is up to? Also, will we not say that what makes of X a “good” philosopher, a “noble” and faithful lover, and a “beautiful” friend can be told from that which would make of X an awful philosopher, a bad lover, and a miserable friend, and that what we can “conceive” and say that “makes” of X a good philosopher, a good lover, and good friend is also that which is “good” and “lovable” and “desirable” about X, whereas any opposite qualities will not be so desirable instead, and that if X hits his children and makes them starve, X will “appear” to us as a hateful father, while we will take X to “be” a loving and lovely father if X loves them and cares for them duly?

Furthermore, will it not be the most natural thing for X to “wish” to be a good father, a good friend, a good lover, a good professor, and even a good philosopher rather than the opposite, and would this wish not “move” him then to become all such things? Plus will we not say that what “moves” X is, in a way of speaking, the same that “drives” X’s family, X’s friends and X’s colleagues towards X, making them willing to be with X, and that, additionally, X’s students will have a greater chance to become good philosophers if X teaches them to think adequately, and that this will “please” them more than the opposite, in the same manner that X’s lover will be “pleased” if X behaves as a good lover, X’s children “pleased” if he is a good father, X’s friends “pleased” if he is a good friend, and X’s colleagues and readers “pleased” – unless they are bad colleagues and bad readers – if X ideas are clear and distinct enough? And will X not get some pleasure from it too, and thus be “pleased” with what pleases them, to the point that it will encourage him to become, if possible, an even-better philosopher, professor, lover, father, and friend? Or will X be pleased to deceive and lose his lover and X’s lover be pleased to be mistreated by him? But then, is there not – as Schiller says – “a necessary connection between perfection and pleasure, and […] a necessary link between self-interest and the interest of others”?

Needless to say, there is always the possibility that all of it or part of it goes amiss, that X becomes a bad friend and a bad professor, or at least a bad lover, while being a good philosopher. And, very likely perhaps, X will not be as good a philosopher as a lover, or will not always be the good friend his friends will expect him to be, for it is not easy to be permanently good, let alone to be good at everything. Yet will we not say that the “ideal” thing would be for X to aspire to be a good friend, father, lover, professor, and philosopher, and that X would be wise if he considers being good in all such cases as a practical regulative principle or goal to which he can commit his life?

There is still the need to explain why being a good lover, etc. would confer some kind of “unity” to X. Let’s agree that X has a body and a mind however we may want to fancy the relation between them, and that just like X’s body has many parts so too X ideas can be many. Will X be a good lover if he merely caresses his lover with the tip of his toes once a month and if he thinks of his lover only occasionally and behaves distractedly whenever his lover needs him, or should X use most of his body to make love to his lover and think about his lover more often and less randomly, so that most of his thoughts and gestures, or at least a sufficient number of them, become involved in his amorous relationship? And even if discrepancies may eventually arise in this respect (“You didn’t pay me enough attention!,” “Oh, I did!”), will it not be obvious to X and to his lover alike that love is not less a demanding thing than philosophy, and rightly so, in the sense that one does not demand exactly the same, nor in the same amount, from a lover and a shopkeeper? Being a good philosopher similarly requires a good many thoughts per day, rather than one or two per year. And in both cases thoughts and gestures must converge into a point regardless of how they do it, for each circumstance is as different as each person is. Now, convergence means “unity.” And if that which “is” and is “intelligible,” that which is “beautiful” and “noble” and “good,” that which is “desirable” and “lovable,” and that which confers “unity” to what we do, if all of it was “divine” for the Plato, this has to do with the fact that – as we have explained elsewhere – the Ancient Greeks employed the term θεός (theos, “divine!”) as an exclamatory expression of awe before that which “shines forth” and “gleams.”

An Indigenous Way of Thinking

Whatever its standards in each particular case, perfection and beauty are of uttermost importance for those who know that all things die and that they, too, will die. With a close eye upon comparative ethnographic research, we can ask: what is perceived as being most perfect and beautiful in any indigenous culture – again, independently from each culture’s own standards? We will obtain a single, straightforward response: that which is most affirmative, most alive, most life-bearing; whereas ugly, instead, is said here and there of that which evokes or is reminiscent of non-being, decay, and death. We have seen it already (here): understood as a condition correlative to the consciousness of death, mortality entails a tragic perception of life; tragedy, in turn, engenders poetry, for, as Pindar says, “things need someone who chants them so as not to lapse into oblivion and death”; tragedy and poetry are the conditions of possibility of care; and care is the condition of possibility of any true dwelling, which necessarily implies putting some valuable things apart to care for them – things that thereby become sacred demanding to be approached with tenderness and respect. Now, that which is most affirmative, most alive, and most life-bearing – that which is beautiful and good – is also that which is most important and hence that which is sacred or divine. As Hölderlin writes, “Whosoever has thought what is deepest, loves what is most alive.” Thus too the fact that in a good many human cultures the youthful and rising deserves the titles of beautiful and perfect. In short, that which is beautiful is being (φύσις [physis], what “shines forth”), and being is the ultimate good. By affirming this ontological parallelism, Plato thematises in philosophical terms the Ancient-Greek educational ideal of the equivalence between the “beautiful and [the] good” (καλὸς κἀγαθός, kalos kagathos), or καλοκαγαθία (kalokagathia) – but in doing so he remains faithful to a still-indigenous way of thinking.

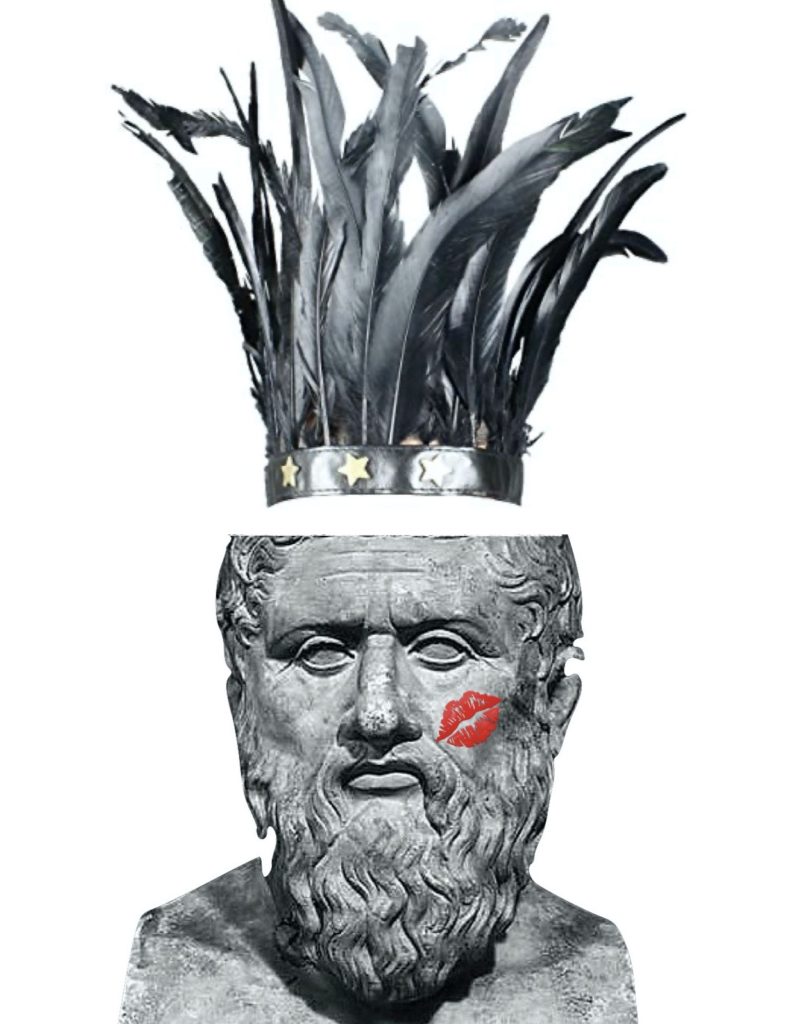

The Becoming-Taboo of Plato

Christianity, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, Nietzsche, Marx, and Freud – not less than pragmatism and utilitarianism, if in a different way – are responsible for having transformed Plato into a taboo, but we will write on this another day. For the time being, we want to reclaim Plato as our totem.(*)

(*) To play here with the title of one of Freud’s writings: Totem and Taboo.

CONTINUED HERE