Certainly not primarily a communication tool. Nor a particular subset of learned behaviour. Nor a cognitive outcome of human evolution. Nor a set of sentences whose truth value could be quantified. Nor a socially-agreed-upon system of sounds and written phonemic symbols or ideograms to which meaning would be conventionally attached too. Nor a disciplinary apparatus of political control. To be sure, language is, or can be, all those things, but it is something else to begin with.

Rousseau (1712–1778) hypothesised a meridional origin for human language and fancied musicality and emotionality, rather than rationality, to have been language’s originally-warm qualities. Rousseau’s phantasy may look naive to us, but it is not absurd in one point, however: emotionality is indeed present in language from the start and not as a secondary aspect; in fact, it is present in it before what we call rationality. Thus, when von Humboldt (1767–1835) says that languages reflect specific conceptual perceptions of the world, he has in mind perceptions that, while having a conceptual side, also have an affective side to them.

Let’s see an example of this. If we look at it carefully, we will see that the phonetic overlapping of the Greek verbs φύω (“to arise,” “to spring up”), φαίνω (“to shine forth,” “to appear”), and φημί (to “say,” to “speak”), all of which begin with the same sound, ph- = /f/, is also semantic, as the three verbs belong in a single semantic field that expressed the idea of “coming forth.” That is to say, there is a semantic equivalence, or equivalence of meaning, when we say that something arises and that something shines forth, or, even more simply, when we say something, for what rises, what shines forth, and what is said or mentioned, becomes present to us, if in different ways. The common conceptual perception, then, behind arising, shining forth, and saying explains the initial phoneme shared by the three verbs: /f/. And if we now consider this phoneme carefully, it will not be difficult for us to discover that it reproduces the sound made by what arises and/or shines forth: ffff…, a sound that, in short, conveys that idea and transmits it in affective terms. Put otherwise, /f/ stands for both a concept and an affect.

Consequently, von Humboldt conceives language as “the eternally-repeating work [or activity] of spirit that makes the articulated sound capable of the expression of an idea,” and affirms that “proper language lies in the act of its actual bringing forth.”

Drawing on Rousseau, Herder (1744–1803), in turn, views language as a something common to humans and animals, in the sense that animals also express their emotions (joy, sadness, expectation, anguish, etc.) with sounds. Yet, according to Herder, human language adds something to this. Paradoxically, however, not something more, but, we may say, something more out of something less. Unlike animals, humans tend to get distracted from their most immediate tasks. As a consequence, their attention becomes dispersed, their perception broadens, and their sensations increase in number, so much so that they become too many and too different. Language allows them to select a number of things on which to focus their attention – the things named – by introducing cuts in an otherwise ever-flowing continuum of sensations.

Heidegger’s philosophy draws on both Herder’s and von Humboldt’s approaches to the essence or being-ness of language. With von Humboldt, Heidegger sees language as an opening that brings forth into the unconcealed that which is (said). With Herder, he views language as that which turns becoming into being.

Pragmatism, empiricism, cognitive science, analytic philosophy, social constructivism, and critical theory, alone or in combination with one another, are unable to capture any of this – that is, they are incapable of letting us glimpse into the essence of language.

Furthermore, defining language, first and foremost, as a culturally-based communication system, is particularly problematic. Because it is not possible, then, to understand that to each language corresponds a world, that each language opens up a different world, so that there are as many worlds or realities as there are languages; that is to say, multiple ontologies instead of one single reality (ours) susceptible of different cultural interpretations.

In short, it is important to go beyond cultural relativism and to think, even more radically, in terms of different ontologies. And thinking language as a worlding event is in turn essential for it. Therefore, the question “What is language?” does not only ask about the essence of language: if formulated properly, it becomes a question about the content and limits of any lived-world.

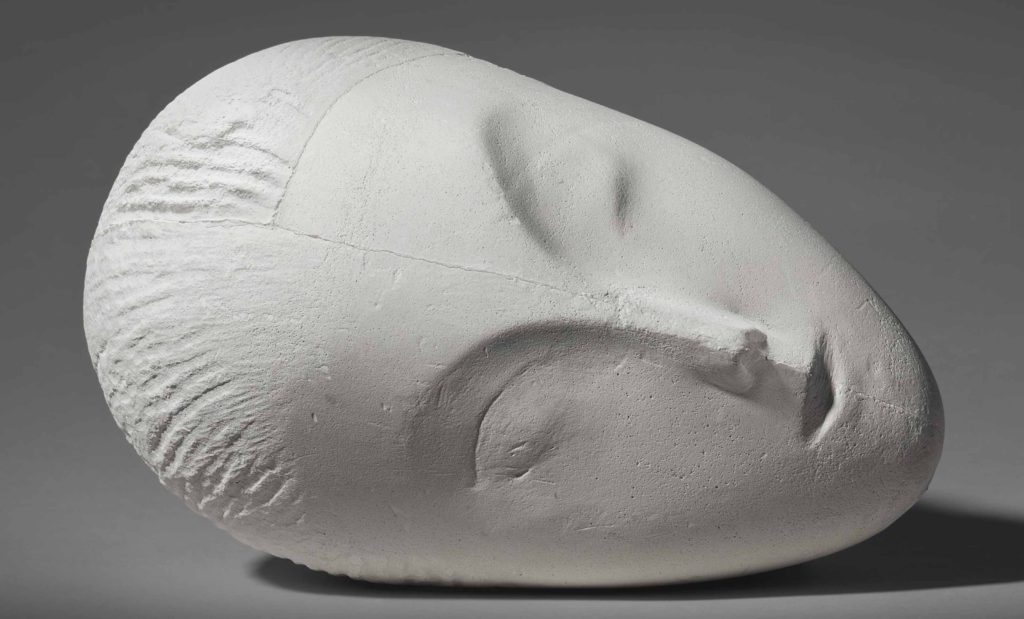

Constantin Brancusi, Dormant Muse I (c. 1909–1910)

Like!! Thank you for publishing this awesome article.

Thank you for liking it! :))